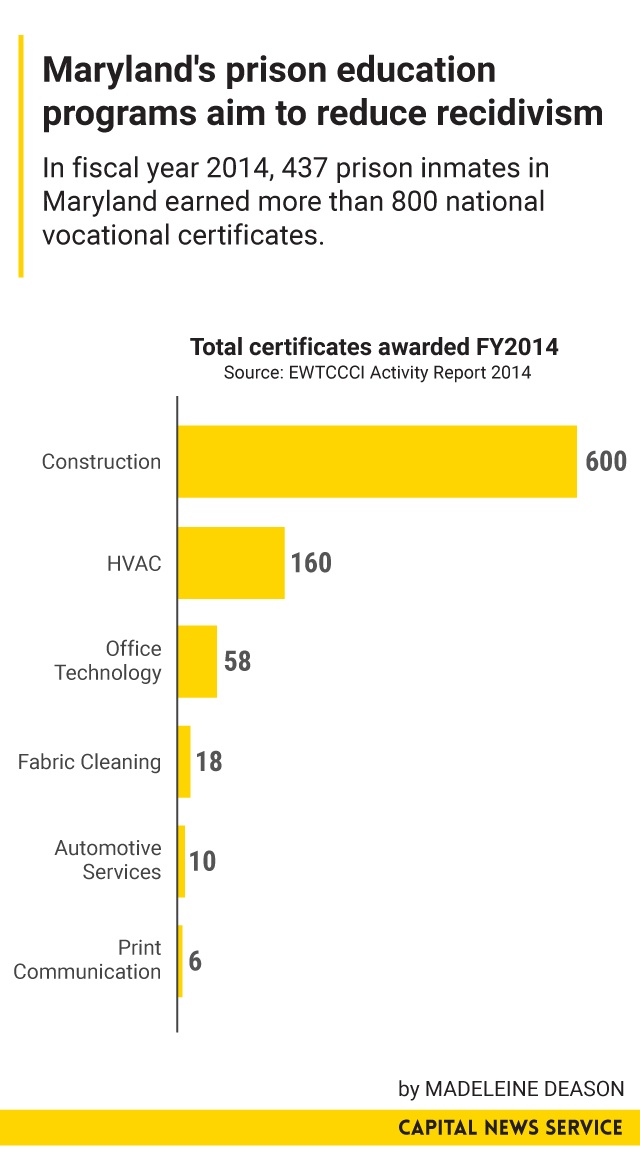

JESSUP — Deval Wallace was always convinced he was terrible at math — until he came to prison.

The 25-year-old moved with his family from Washington, D.C., to Maryland while in high school. The courses in Maryland were more advanced, Wallace said, and he fell behind, eventually failing all of his math courses.

Wallace graduated, but any thought of pursuing an education was halted when, at age 20, he was convicted of attempted murder in 2010 and sentenced to 45 years in prison.

But when Wallace was accepted into the Goucher College prison education program, something unexpected happened — he liked math. He understood it.

“When I got to pre-algebra, my professor — man, he broke that thing down so simple,” said Wallace, who now takes statistics.

Thanks to the Goucher Prison Education Partnership, a division of the private Baltimore liberal arts college, the program grew out of existing efforts by faculty, community members and students, kick-starting free education for 15 students in prison in 2012.

The partnership’s goal was to continue “growing ambitiously, but sustainably,” Amber Roza, the director of the partnership, said.

Wallace is now one of 70 students enrolled in Goucher College within the Maryland prison system.

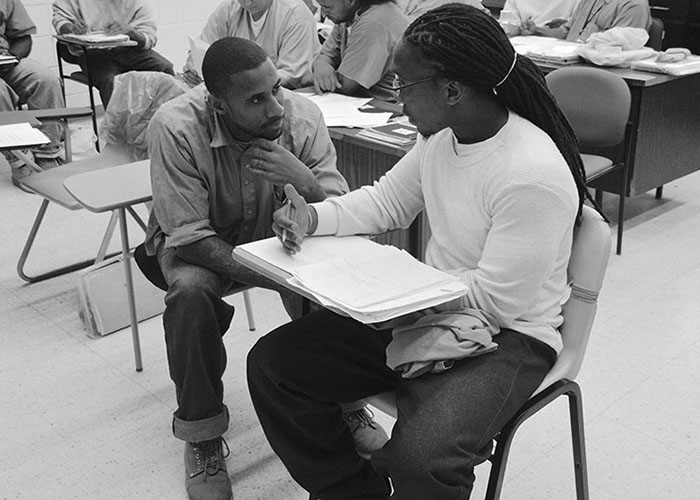

The classes, averaging out to between 15 and 25 students per professor, take place mostly in the afternoon or evening, allowing prisoners with jobs or other responsibilities to take part, Roza said.

With a typical minimum of two classes per semester, students take a combination of three- and four-credit general education courses that fulfill the Goucher degree requirements, Roza said — giving inmates the opportunity to continue higher education upon release.

“(Goucher tries) to offer classes that are highly transferable, and useful to (the inmates) elsewhere,” Roza said, with many students taking a foreign language, history or math courses — often core requirements for a bachelor’s degree.

Goucher student and Maryland Correctional Institute Jessup inmate Joseph Clark, 23, said he intends to continue his education upon release.

In the prison library, Clark’s face lights up as he describes algebra as “out of this world.” He notes the intricacies of lines and drawing, which he learned about in Art 101, and he beams about his newfound knowledge when it comes to writing.

“I used to write letters all day (but there’s) so much about writing that I didn’t know before that Goucher has taught me,” Clark said, crediting his English 105 course, which teaches grammar, and helps students form arguments and personal voices in their writing.

Goucher College lecturer Mary Jo Wiese, who teaches the academic writing course at both the men’s and women’s Jessup prisons, said her experience with the men is hard to put into words.

Wiese, of Towson, was particularly struck by one assignment when she asked the inmates to write a personal essay on how they first learned to read and write.

The narratives, incredibly powerful, were also somewhat infuriating, Wiese said, revealing that some of the men in her classroom had gotten through the public school system despite being illiterate.

“The men are incredibly motivated (and) extraordinary diligent. There’s a kind of maturity (and they are) eager for criticism,” Wiese said.

The students also have decades of experience, Wiese said, a contrast to the the freshman English classes she teaches at Goucher College’s main campus in Baltimore.

“The men are incredibly motivated (and) extraordinary diligent. There’s a kind of maturity (and they are) eager for criticism."

—Mary Jo Wiese, Goucher College Lecturer and writing teacher at Maryland Correctional Insitution Jessup

“There were two men who talked about learning to read after they were incarcerated, and having fellow inmates teach them,” Wiese said.

Walter Lomax, 67, didn’t learn to read until he went to prison.

Wrongfully convicted of a robbery and murder in 1968, Lomax entered prison innocent, and functionally illiterate, in his early 20s.

During his 39 years in prison, Lomax pursued his education, eventually obtaining his GED and an associate’s degree from Essex Community College before he was found not guilty and released from prison in 2006.

“When I went to prison, I could barely read or write. It literally changed my life,” Lomax said of the education he received in prison. “It also changed the mind of others that otherwise wouldn’t have gotten that education.”

Lomax now serves as the director of the Maryland Restorative Justice Initiative, an organization that advocates for fair treatment and sentencing policies in Maryland prisons for inmates serving extended sentences.

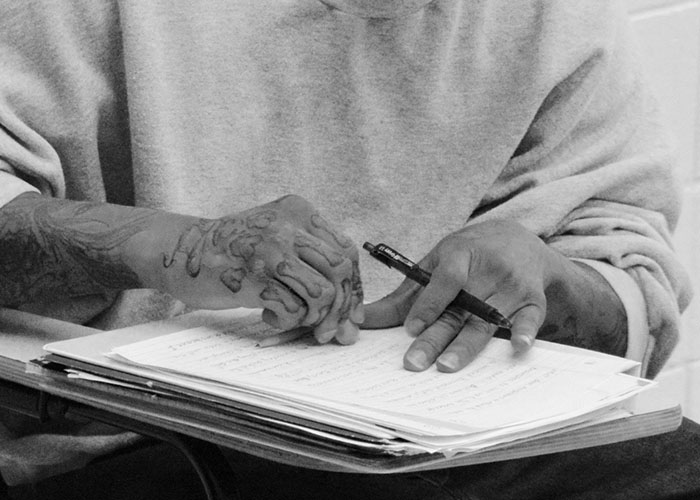

A 2014 activity report from the Education and Workforce Training Coordinating Council for Correctional Institutions revealed that for the 23,000 inmates who were in the Maryland prison system, their average reading level was between the sixth and eighth grade.

Fewer than half of those inmates had a high school diploma when incarcerated.

Roza, also an academic adviser for the inmates taking classes with Goucher, said that the program does not screen inmates based on the duration of sentence, commitment offense, disciplinary history or age, and has received more than 500 letters from Maryland inmates expressing interest.

“We think it’s important that students from all those different categories are included,” Roza said.

The only obstacle in their way, Roza said, is funding.

“When I went to prison, I could barely read or write. It literally changed my life."

—Walter Lomax, Director of Maryland Restorative Justice Initiative

While Anne Arundel, Hagerstown and Wor-Wic community colleges are offering courses to inmates at the prisoner’s own expense, Goucher is the only college in the state of Maryland offering credit classes at no cost to the students in prison.

The Goucher Prison Education Partnership is fully funded by private grants and partnerships with several organizations, including The Warnock Foundation, the Zanvyl and Isabelle Krieger Fund, Advocates for GPEP, the Baltimore Women's Giving Circle and The Bard Prison Initiative and The Open Society Foundation.

The growing partnerships help pay for each inmate’s tuition, amounting to around $6,000 a year after in-kind donations, which include books, calculators and volunteer hours, providing the program with essential resources with no hard costs, Roza said.

Tuition also includes all educational necessities, including instructional materials, books, administration, tutoring, office hours and college prep courses during the 15-week-long semesters.

And while Goucher plans to raise more than $380,000 for the program costs this year through grants and private partnerships, Roza said, it’s still not enough to serve the many prisoners who are seeking an education.

“If we had more funding, we could create more positions,” Roza said, allowing more professors to teach additional courses.

One state and one federal bill aiming to create more educational opportunities and access to financial aid for prisoners are underway.

The federal bill, proposed by U.S. Senate candidate Rep. Donna F. Edwards, D-Fort Washington, will include Federal Pell Grants for prisoners, an opportunity that was banned starting in 1994.

In May, Edwards introduced the Restoring Education and Learning (REAL) Act, with hopes to reinstate Pell Grant eligibility for both federal and state prisoners, which provides a maximum of $5,775 to full time students in the 2015 to 2016 school year.

In September, Edwards hosted a panel on prison called "Education Behind the Wall: Breaking the Cycle of Incarceration” during the Congressional Black Caucus Annual Legislative Conference.

“Donna is building support in the House, talking about this issue in Maryland and all over the country, and getting more and more people excited about making Pell Grants a reality for everyone,” said Ben Gerdes, Edwards’ director of communication, noting that gaining support from Republicans has been one of the biggest challenges. “And frankly it’s time. Giving incarcerated individuals an opportunity to get an education is the right thing to do both economically and morally.”

“It gets people out of the state of mind that you were incarcerated. Even a guy who’s serving a life sentence right now, he still wants education. And he knows he’s not going home, but he still wants education."

—Joseph Clark, inmate at Maryland Correctional Institution Jessup and Goucher College student

After the Obama Administration and the U.S. Department of Education announced the Second Chance Pell Pilot program in July to test new models granting prisoners federal funding for post-secondary education, Maryland state senator and member of the Senate Education Subcommittee Jim E. Rosapepe also announced in July that he was drafting a bill to boost college education funding for prisoners.

With the help of the Maryland Higher Education Commission and the Maryland Department of Public Safety & Correctional Services, Rosapepe’s bill aims to equip college-ready prisoners with skills by creating more partnerships between state colleges and state prisons and promoting a range of courses that will prepare prisoners for a successful reentry into society.

A second chance at education

All prospective Goucher students must go through the full application process, involving an orientation, in-person interviews and placement exams, which determine whether the applicant is prepared for college work.

If applicants don’t have a GED or high school diploma, or are simply missing essential academic skills, they can take remedial classes offered within the prison or the Goucher College prep classes, Roza said.

"The point of what we’re doing is (offering) a college education for men and women who are also incarcerated, and supporting them and developing them as scholars and leaders," Roza said. "When you do that really well, you get some really important outcomes."

According to a recent RAND Corp. study, inmates who participated in a correctional education program had a 43 percent lower chance of returning to jail and a 13 percent higher chance of employment after release than inmates who did not receive education while in prison.

The Pew Charitable Trusts revealed that the number of people admitted into Maryland prisons has decreased by 19 percent in the last decade. A Bureau of Justice Statistics study of prisoners in 2014 showed that state prison admissions decreased nationwide by nearly 11 percent from 2004 to 2014.

Rosapepe’s goal is to continue that trend by using correctional education programs to reduce the number of people who return to prison.

“To the extent that we can help prisoners while they’re in prison (and) help them earn money legally when they get out of jail . . . . It’s totally in the taxpayer’s interest as well as in the prisoner’s interest for them to develop skills, and I emphasize -- to earn money legally when they come out,” Rosapepe said. “Because when they come out, they still got to make a living and if they do it by returning to a life of crime, that hurts the law-abiding citizens and it puts them right back in prison, which costs the taxpayer.”

With the Goucher prison education program being fairly new, official recidivism rates are not yet available. But they are likely similar to those at Goucher’s sister program, the Bard Prison Initiative in New York, where only 2 percent of students who participated in the program before their release have returned to prison, Roza said.

Seventy-seven percent of the students in the Goucher program at the Maryland prison are first-generation college students, and more than half have children, Roza said, making prisoners’ access to education even more vital.

“The access for first-generation students changes their lives and community, and lives for their families,” Roza said. “Everything we’re talking about – education attainment, income, and recidivism – all those things have such a huge impact on our future.”

In prison for the past four years for robbery charges, Joel Moreno, 22, from Hyattsville, said he first truly grasped the importance of education from what he calls the “lifers” — inmates who have been sentenced to life in prison.

Soon after Moreno arrived at Maryland Correctional Institution Jessup, the “lifers” explained that with his initial naiveté and hotheaded temper, Moreno could turn his 10-year sentence into 25-to-life.

“They just started giving me books . . . and they would ask for reports,” Moreno said. “They stayed on top of me.”

Moreno’s next step was Goucher.

After walking past a box in the prison with Goucher’s name on it, Moreno wrote letters to the college inquiring about the program for a year before receiving a response.

From there, he said, it was destiny.

"Education is just my thing now. It’s my outlet. Some people use weights. Some people like to read. Mine is just education," said Moreno, who has excelled in his courses and is now taking an English course, Algebra, African-American History and Creative Writing – the maximum number of courses allowed.

Benefits of correctional education

With 36 percent of prisoners sentenced to more than 15 years in prison, according to an April 2015 quarterly inmate characteristics report from the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services, Rosapepe also argues that time and location are all on the prisoner’s, and the taxpayer’s, side.

"Two of the problems you have in traditional colleges is getting people to show up for class and having buildings to have the classes in. You don’t have that problem with prisoners. They have buildings and they have perfect attendance," Rosapepe said. "Most of (their) sentences are much longer than a Ph.D. program, so they have time."

Clark, sentenced to 17 and a half years in prison for armed robbery in 2012, agreed.

“In my eyes, I feel like we have all the time in the world. Of course, sometimes you’ll have to sacrifice recreation or gym, or (going) outside, but I feel as though (those) are not essential,” said Clark, who also works as a school clerk at the prison, helping file paperwork for other inmates looking for education. “I could never make the excuse to say that I don’t have enough time to do my homework.”

Enrolled at Goucher since 2013, Clark said he initially thought doing the program would get him home earlier. Only later did he realize how much he didn’t know, and how education was, in fact, freeing.

“It gets people out of the state of mind that you were incarcerated,” Clark said. “Even a guy who’s serving a life sentence right now, he still wants education. And he knows he’s not going home, but he still wants education. And I think that’s a beautiful thing.”

And from the taxpayer’s point of view, taxes are already used to house and keep prisoners safe, Rosapepe said.

“We literally could keep them in prison but open up the world to them in a very positive way.”

—Jim E. Rosapepe, Maryland state senator

According to Roza, it costs around $37,000 a year to incarcerate a person in Maryland prisons, and less than an additional $6,000 a year to fund an inmate’s Goucher education while in prison.

Challenges to funding

But with more than 121,000 people in Maryland receiving Pell Grants for the 2014 to 2015 school year, many wonder whether the proposed bills will decrease the amount of funding available to those “on the outside” who are seeking education in order to accommodate prisoners, if passed.

“For me, the devil is always in the details,” said Maryland state Sen. Gail Bates, R-Howard, in anticipation of Rosapepe’s bill.

“I’d have a problem if it were choosing between prisoners and, let’s say, graduating high school students going to college. If it’s an additional funding source, then that’s a different story,” said Bates, who served on the legislature’s 2014 budget subcommittee for the Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services.

Roza, however, said there’s little need for concern.

When Pell Grants were lawfully granted to prisoners from 1972 to 1994, incarcerated individuals accounted for fewer than 1 percent of total Pell Grant recipients in 1993 to 1994 – and that was at the height of total applications.

Thinking beyond the limits

Other challenges to the bills relate to the logistics of expanding prison education.

Inmate Clark said there are limitations.

“The most challenging part is information and research,” Clark said. “You would want to know more about certain things, but we’re limited. We don’t have access to the Internet.”

Understanding the security rationale behind inmates being banned from Internet access, Rosapepe said he hopes to explore the possibility the use of the World Wide Web as a teaching resource.

“The Internet is a fabulous educational tool, and to say that if someone goes into jail in 2015 for 20 years, they’re not going to be exposed to the online world until (2035) is kind of crazy on its face,” Rosapepe said. “Many jobs require digital competency and so that’s part of the things people need to learn.”

With free online educational services like Massive Open Online Courses, or MOOCs, Rosapepe said, prisoners are perfect potential students for online courses, which could also alleviate the need for instructors to be physically present within the prisons.

“We literally could keep them in prison but open up the world to them in a very positive way,” Rosapepe said.