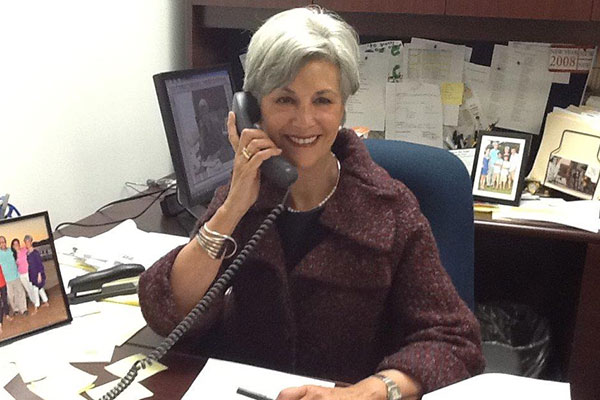

Sandy Hillman wants to see more women in management. Hillman says that women bring special sensitivities and ways of thinking to the job. Photo by Tazeen Asiya Ahmad.

By TAZEEN ASIYA AHMAD

Capital News Service

One Woman Puts Cracks In The Glass Ceiling

WASHINGTON - Sandy Hillman, 73, went from being a magazine editor on Madison Avenue to working for the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson in the early 1960’s. It was a time when fewer women were in the workforce and fewer opportunities existed for those who were.

But that didn’t hold Hillman back. She went on to serve as a close adviser to four-term Baltimore Mayor William Donald Schaefer, and was dubbed “the impresario of urban America” by Time magazine for her role in transforming Baltimore’s Inner Harbor into a world-class tourism destination.

Hillman left city hall to run the prominent public relations firm Trahan, Burden and Charles, whose clients included then Mayor Martin O’Malley.

Six years ago she started her own company, Sandy Hillman Communications. Earlier this year, the Daily Record named her one of Maryland’s most influential people.

Despite her success, Hillman has been not immune to some of the prejudices that continue to exist for women in the workplace.

“There have been times when I have been in a room with men who work for me and it is assumed that they are my superiors,” Hillman said.

She said it hasn’t happened to her much, but when it does, she finds it amusing rather than annoying.

As a business owner and as a woman Hillman is very cognizant of the challenges faced by working women, particularly working mothers.

She’s always made an effort to incorporate family-friendly policies in work environments that she’s managed.

“That means letting people work from home either occasionally or full-time. And managing a workforce so people who work very hard and many hours can still find time for some balance in their lives,” Hillman said.

A big proponent of raising the minimum wage, and paid sick and family leave, Hillman also supports the Paycheck Fairness Act that her pal, Sen. Barbara Mikulski, D-Md., has been pushing for in Congress.

Commenting on the Maryland General Assembly’s move to raise the minimum wage in the state to $10.10 by 2018, Hillman said it should have been raised higher and should have gone into effect much faster.

“I think it is criminal to expect people to essentially live and raise their children with a sense of hope and opportunity if they can’t feed themselves and their kids, can’t rent a home. It’s wrong,” Hillman said.

Hillman started working in 1963. After graduating from Penn State University with a degree in English and chemistry, she headed to New York and landed a job as a magazine editor. Two years later she joined an advertising agency, where she quickly climbed the corporate ladder, making a substantial salary.

Hillman’s path was not a common one for women at the time.

“The majority of women I graduated from college with were in education. They got married and they didn’t work, or they taught for a short time,” Hillman said.

She attributes her success as a working woman to her parents. They surrounded her with constant positive reinforcement and made her believe she could do anything.

“It was at a time of great change for women in America. There was certainly less opportunity than there is today,” Hillman said.

But the glass is half-full outlook she has about life, she said, has served her well. It also helped that she had great female mentors early in her career.

“These women encouraged me and made me much more self-aware. They helped me equip myself to understand the direction I should take professionally,” Hillman said.

In spite of her parents’ overwhelming support and strong female role models, when she looks back on her life, Hillman said she still made career choices based on her gender.

She decided not to go to law school, which had been her initial plan, because so few women were in law school at the time.

She had also thought about being a chemist, but changed her mind after seeing what she thought was prejudicial behavior against women in the lab she worked at for two summers while in college.

“I worked under two women at different times. Both had Ph.D.’s, and both were extraordinarily talented. They never received the recognition in those labs that they should have,” Hillman said.

In 1964 Hillman got married and two years later she and her husband moved from New York to Washington.

Apart from the obstacles she faced being a woman, Hillman encountered another unexpected hurdle when she started looking for work in the district.

“There were jobs I didn’t get because I was Jewish. I was shocked by it because I had never been confronted with anti-Semitism in my entire life, until then,” Hillman said.

She did get with a job in the Johnson administration where she worked for two years, before moving permanently to Baltimore.

In Baltimore, Hillman became the executive director of the Baltimore Office of Promotion and Tourism, working for then Mayor Schaefer’s office, which she said was the best job in America.

“The mayor was somebody who was a great supporter of women. He was an extraordinary leader and a great mentor for all of us,” Hillman recalled.

As a working mother, Hillman recognized that she couldn’t have kept doing what she was doing without the help of another woman who would play an important role in her life – her housekeeper, Gladys Moore.

“I couldn’t have raised my kids without her and she tells me she couldn’t have raised her kids without me,” Hillman said.

She said it was less expensive than what everybody pays for childcare today. “It was a different time,” Hillman said.

She sympathizes with today’s working mothers who struggle to find affordable childcare. Today, after 50 years in the workforce, Hillman’s advice to working women is that they don’t have to behave like men to succeed.

“Women bring very special sensitivities and ways of thinking to management and problem solving. I think that those things are very important for the workplace,” Hillman said.