In the 1880s, election fraud and a massacre stopped Black progress

White supremacists and newspapers conspired to take down a progressive, integrated party in Danville, Virginia

By Molly Castle Work and Rachelle Keaton

DANVILLE, Va. — On Nov. 4, 1883, a white mob, fearful of Black political power and riled up by false newspaper narratives, took to the streets of Danville three days before the election and used a fist fight between a white man and a Black man as justification for a violent massacre.

Four Black men were killed that night, but the violence continued for three days as armed white men patrolled the streets — threatening to shoot any Black citizens who dared to leave their homes and vote in the statewide election.

By the time the state militia arrived to restore peace in the city, the election had passed, several Black men had been beaten or shot and six Black men had been murdered.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

On Nov. 4, 1883, the Richmond Dispatch, a leading white newspaper, wrote, “These negroes had evidently come to regard themselves as in some sort the rightful rulers of the town. They have been taught a lesson — a dear lesson, it is true … but nevertheless a lesson which will not be lost upon them, nor upon their race elsewhere in Virginia.”

The Reconstruction era, following the Civil War, had featured tremendous opportunities for Black advancement as the federal government moved to make newly freed people equal members of society.

Danville was on track to become a politically progressive, economically prosperous city led by an integrated government. Black residents had taken on prominent positions in government and business. White and Black citizens had created a new political party, dubbed the Readjusters, to advocate for progressive goals such as public education.

It did not last.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

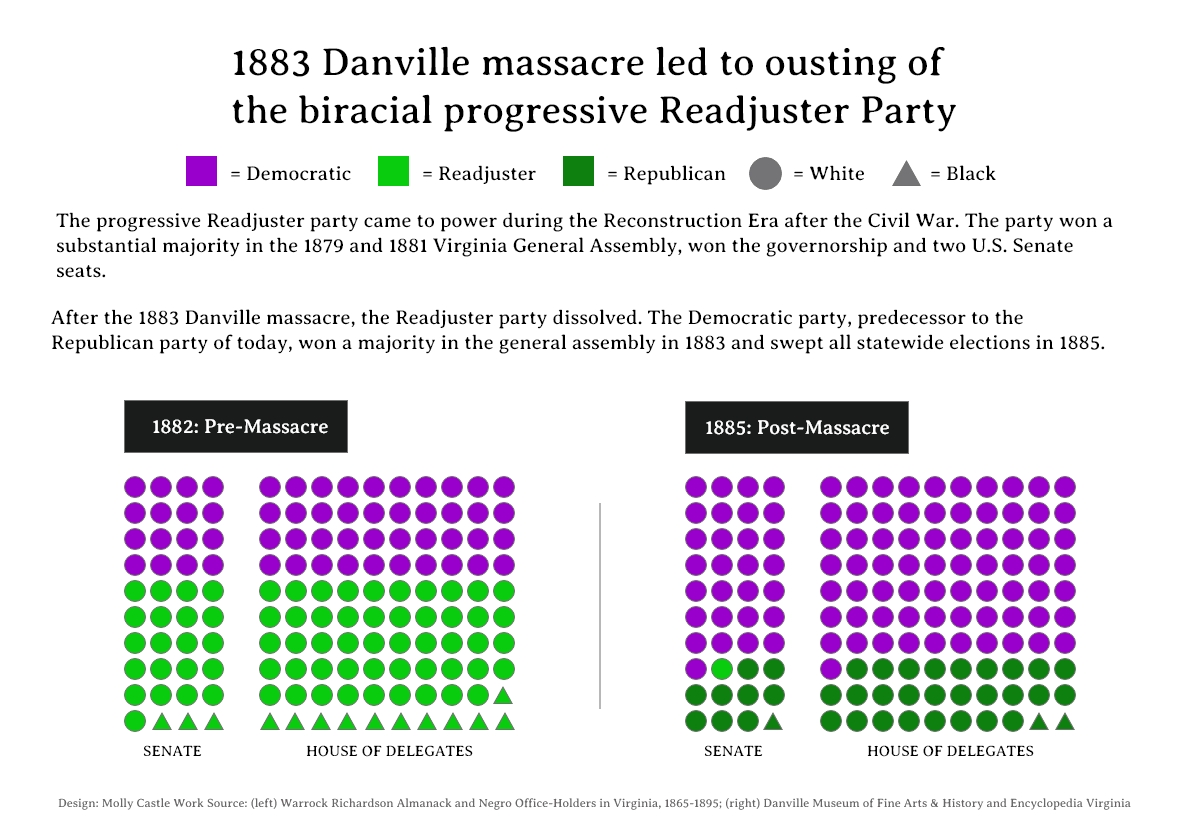

The 1883 massacre stole all hopes of a victorious Reconstruction for Black Danvillians, said Ina Dixon, a local historian. The Readjuster Party, one of the most successful examples of progressive interracial politics in the post-Civil War South, was torn apart, and momentum toward Black economic power came to a halt.

White-owned newspapers didn’t condemn the massacre in their coverage. Instead they celebrated it as Virginia’s redemption. In the Danville Times’ coverage of the event, the local newspaper’s headline referred to the election results immediately following the massacre as a “GLORIOUS VICTORY!”

“The newspapers helped to justify the violence of the Danville massacre,” Dixon said. “It helped to justify the stripping away of voting rights for citizens of the country and justify this idea of, for now and ever more, white people are on top.”

Reinforced by coverage from white-owned newspapers, the effects of the Danville massacre are felt to this day, said Deputy Police Chief Dean Hairston, who is also a local historian. “Danville was segregated until the 1960s and it is still socially segregated today,’’ he said.

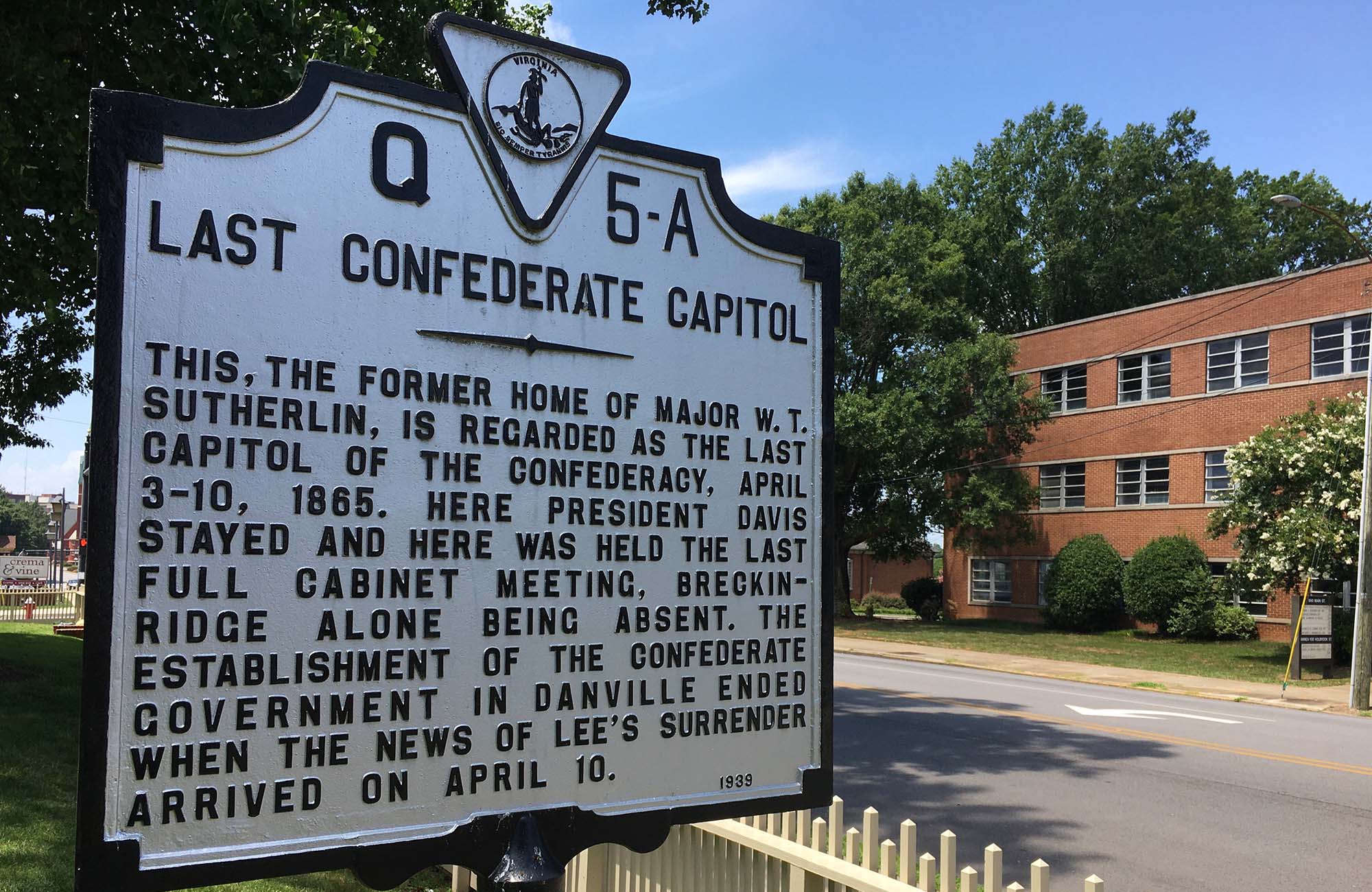

Evidence isn’t hard to find. Every Saturday for the last six years, the Sons of Confederate Veterans have towed lawn chairs to the city center to protest the banning of the Confederate flag from public spaces in Danville, the last capital of the Confederacy before Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox. Confederate flags fly outside private homes, dot the graves at local cemeteries and greet drivers at every roadway into this former mill town.

“Because of the massacre, you saw Blacks pushed out of the city,” Hairston said. “You saw voting patterns change. You saw this start of an informal dominance over African Americans. … It would take the Black community about a century to recover.”

Progress and resentment

The Readjusters came to power in the late 1870s during the turbulent Reconstruction era. The progressive political party worked to fund public education, reduce the war debt and redistribute wealth — drawing support from both white Republicans and Black Americans.

“The glue that held this unlikely coalition together was a shared desire for state services,” said Jane Dailey, a historian and University of Chicago professor.

The Readjusters amassed tremendous influence in Danville, a majority Black city, by electing Black officeholders. More than half the seats on the city council were occupied by Black Americans, and the Readjusters hired Black policemen and selected a Black citizen as director of the marketplace.

Less than 20 years after the Civil War ended, Black Danvillians had gone from being in bondage to holding prominent positions of power. However, this advancement was met with resistance.

White supremacist Southern Democrats in the 1880s experienced deep anxiety, frustration and resentment about Black economic advancement and power in the leadup to the Danville massacre, historians say. (For decades after Reconstruction, Black voters supported the Republican Party, which they saw as the party of Abraham Lincoln. That allegiance shifted over time to the Democratic Party, with dramatic movement after Democrats pushed for civil rights and voting rights bills.)

White Democrats were enraged that “insolent” and “uppity” Blacks, as they were referred to in Richmond Dispatch coverage, had the audacity to exert their hard-won rights, like voting and holding office. They used newspapers as an avenue to regain control and justify a Black social position at the bottom of the racial hierarchy, Dixon said.

Printed Strategy

“Throughout the 1883 election season, the Democrats incited racial animus through inflammatory reports and commentary about ‘Negro misrule’ in newspapers across the state,” Kathy Roberts Forde wrote in “Journalism and Jim Crow: White Supremacy and the Black Struggle for a New America,” the book she co-edited.

White-owned newspapers injected false narratives into their articles to gin up white hysteria, Dailey said — writing about rapes that hadn’t occurred and crimes that hadn’t been committed — all in the interest of crushing Black citizenship and Black participation in government.

Unlike today, where newspapers strive to avoid conflicts of interest, the white-owned Democratic newspapers in Danville at the time were openly politically aligned and often affiliated with white supremacist leaders, Dailey said.

“They were being operated as propaganda machines,” said Forde, a historian and professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

“White supremacist Democrats were determined to win seats in the election, so they developed a strategy to use the specter of ‘Negro domination’ to drive a wedge between the Black and white Readjuster coalition,” Forde wrote in “Journalism and Jim Crow.”

A key tool was the “Danville Circular” — a Democratic Party publication that contained a litany of complaints about the supposed conditions of life in Danville under Black “misrule.” The Circular traveled widely around the state in the days before the election, Forde wrote. It was republished in Democratic newspapers, including the Richmond Dispatch.

The language in the Circular inflamed white citizens, Dailey said. Newspapers republished the claims that, although there was an African American majority in the community, Black people weren’t paying their fair share of taxes. The Circular also wrote that “misrule of the radical or negro party” had changed the city for the worse.

“The market, once occupied in all its stalls by polite white gentleman, with clean white aprons, and the most inticing meats and vegetables upon their boards, is now the scene of filth, stench, crowds of loitering and idle negros, drunkeness, obscene language and pettit thieves,” it said. “The white men have been driven out.”

Dailey said the newspapers’ promotion of the Danville Circular helped to spread the narrative that white people in Danville needed to be rescued by Virginia Democrats and that the Readjusters had to go.

Violence and voter fraud

The day of the massacre, a fist fight drew a crowd. And white Democrats, who had gathered for a political meeting, began shooting indiscriminately into a crowd of bystanders — about 100 Black women, men and children. The violence continued for days.

White news coverage framed the Danville massacre as a riot and blamed African Americans for inciting the violence, Hairston said.

“The negroes have precipitated the bloody issue, and the whites have been forced to meet it with arms in their hands,” the Lynchburg News wrote.

The white-owned newspapers helped to calcify the idea that the Danville massacre was a return to normal and Virginia was redeemed, a return to the racial hierarchy they knew from slavery, Dixon said.

Meanwhile, the Black press worked overtime to share the truth of the massacre, Dailey said. Black newspapers shared details of the violence, highlighted parallels between similar massacres of Black voters in the South, and stressed that the Danville episode was a massacre, not a riot.

Three days later on the state’s Election Day, few Black Danvillians headed to the polls, fearful for their lives as armed white Democrats continued to roam the streets. Democrats took back political control.

The Readjusters lost in part because of the limited Black vote in Danville but also because the news coverage convinced large numbers of white Readjusters to join the Democrats, Forde wrote in her book.

The white newspapers picked up the story in Danville, and broadcast to the entire state, Dailey said. In the state election, the Readjusters lost across the board.

In the aftermath of the Danville massacre, white citizens, including co-conspirators of the movement to remove Black citizens from political participation, were elected to the Danville city council, Hairston said. Many African American citizens were displaced and forced to start settlements on the outskirts of town.

After the 1883 election, the Readjuster Party was no longer a factor.

By 1885, the Democratic Party had captured all statewide offices, according to Encyclopedia Virginia. White supremacists held political sway for decades, and the African American community began winning seats on the city council only in the 1960s, more than 80 years later.

“The Danville massacre is really important because it shows the lengths to which white supremacists will go to regain political power in the South,” Dailey said. “They couldn’t win a fair election in Danville, so they turned to violence and election fraud. They were uncommitted to the democratic process. If that sounds familiar today, well we’ve been there before.”

The legacy

The massacre changed Danville. It was the end of biracial politics and created a new iteration of discrimination and segregation that are felt today in the town of 40,000 on the North Carolina border, Dixon said. African American citizens moved to segregated Black neighborhoods, Black businesses closed and the majority Black city became majority white.

The Sons of Confederate Veterans drive around town with large Confederate flags attached to their vehicles, Hairston said. They protest weekly with their flags in front of the city museum. Hairston said some Danvillians oppose their presence, but passing cars honk in support.

The city today, once again majority African American, is led by a Black mayor and more than half of the city council seats are held by African Americans, Hairston said.

Karice Luck-Brimmer, a genealogist and public historian, is heartened by Danville’s recent progress, but is frustrated thinking how much further along the African American community could be, had the massacre not stalled Black advancement.

“It makes you sad and makes you angry,” Luck-Brimmer said. “You just start to think about where your people would be socially and economically if certain things hadn’t taken place — not only here in Danville but across the South. … It’s just one of those feelings that doesn’t go away.”