By Christina Armeni

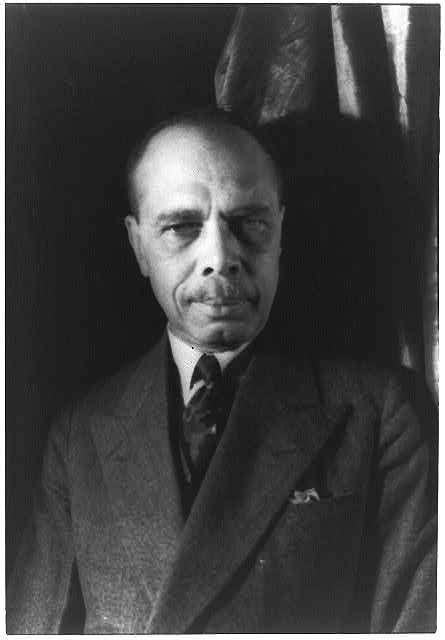

The words were meant to be spoken, not sung. It was supposed to be a speech honoring Abraham Lincoln—born nine decades earlier, assassinated half a century later, yet still revered at Stanton Normal High School in Jacksonville, Florida, where the principal was a son of the city, James Weldon Johnson.

The speaker-to-be decided instead to focus on those freed from slavery by the Emancipation Proclamation rather than the President who had issued it.

“Johnson shifted it to emphasize the voices of the emancipated, reflective of Johnson’s emphasis on the voices of Black people, and the importance of listening to the voices of Black people for the nation to become the all of the ideals that it strives for,” University of North Carolina at Greensboro professor Noelle Morrissette, said in an interview.

“He didn’t feel like writing about Abraham Lincoln at that time. So he wrote this song,” said Morrissette, author of “James Weldon Johnson’s Modern Soundscripts.”

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

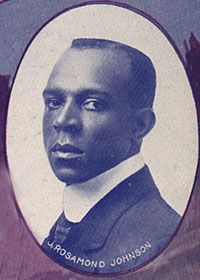

His brother, John Rosamond Johnson, set the words to music, and some 500 young voices sang it at that commemoration in 1900. “Shortly afterwards my brother and I moved away from Jacksonville to New York, and the song passed out of our minds,” Johnson would recall.

Till earth and heaven ring

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise

High as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

“But the school children of Jacksonville kept singing it; they went off to other schools and sang it; they became teachers and taught it to other children. Within twenty years it was being sung over the South and in other parts of the country”:

Lift every voice and sing

Till earth and heaven ring

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise

High as the listening skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

More than 100 years later, the Johnson brothers’ collaboration has been celebrated as a national anthem by, about and for African Americans. James, for one, never intended that to be, Morrissette said.

“In Johnson’s lifetime,” she said, “he actually was very careful not to call it ‘the Black National Anthem,’ or ‘the Negro National Anthem.’ He called it the Negro national hymn. … He did not want to advance Black beauty and Black equality at the expense of citizenship.”

Harvard University historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. said the song is emblematic of its time when multi-talented Black women and men felt an obligation to use those talents not only to push back with words against lynching and Jim Crow injustice, but also to put their bodies where their thoughts were, and to express those views in newspapers, magazines, books, theater and music.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

“Because the poem constitutes the lyrics to this anthem, it is undoubtedly the most popular poem—at least its first verse—ever written by an African American poet,” Gates wrote.

“Its second verse is a lesson in black history, a meditation on the history of the Negro from Reconstruction through Redemption to the birth of a New Negro at the turn of the century,” Gates wrote in the preface of his 2019 book, “Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow:”

Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat,

Have not our weary feet

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

In 1827, more than four decades before Johnson was born, Samuel Cornish and John B. Russwurm launched Freedom’s Journal, the nation’s first newspaper owned and operated by Black men. Twenty years after that, Frederick Douglass published the first editions of The North Star.

Both were anti-slavery publications, centered in the North, where the relative sliver of free African Americans lived. Most African Americans still were in the South, where they had been enslaved, forbidden from voting or owning property, and in most instances, not allowed to learn to read or write.

Johnson’s parents had not been enslaved in America. They came from Caribbean islands where African descendants had years earlier rebelled against bondage and overcome barriers still denying full citizenship and life to those in North America. Stephen Dillet, Johnson’s maternal grandfather, had won election to the Bahamian legislature in 1833, the first man of color to do so.

James left home at 16. He went north to Atlanta University, initially to complete his secondary education because at that time high schools in Jacksonville were closed to Black people. He would spend seven years there, leaving in 1894 with a bachelor’s degree and returning to Jacksonville to become the principal at Stanton, where his mother had taught music.

Only a year after being back home, and while still a teacher and principal, Johnson founded the Daily American, said to be the first Black-oriented daily newspaper in the nation.

Its goal was to encourage education and self-achievement, and to speak out against racial injustice. It failed, though, to generate sufficient financial support, and was out of business within a year.

James went north again; his brother, too.

Cornish and Russwurm’s Freedom’s Journal, like Johnson’s Daily American, had a short life, ending publication in 1829, two years after it began. Other Black newspapers had come and gone, and by the beginning of the Civil War, more than two dozen were in operation.

The New York Age was one of them, and four years after the premiere of “Lift Every Voice,” James Weldon Johnson was editor of The Age. It had been established in 1880 and early on developed a reputation as a stalwart crusader against lynching.

Unlike other editors at Black newspapers of the time, Johnson signed his name to his editorials, and advocated a Black press where progress of the race took priority over private economic stability.

“Negro weeklies make no pretense of being newspapers in the strict sense of the term,” he wrote in an October 22,1914, edition. “They have a more important mission than the dissemination of mere news. …They are race papers. They are organs of propaganda.”

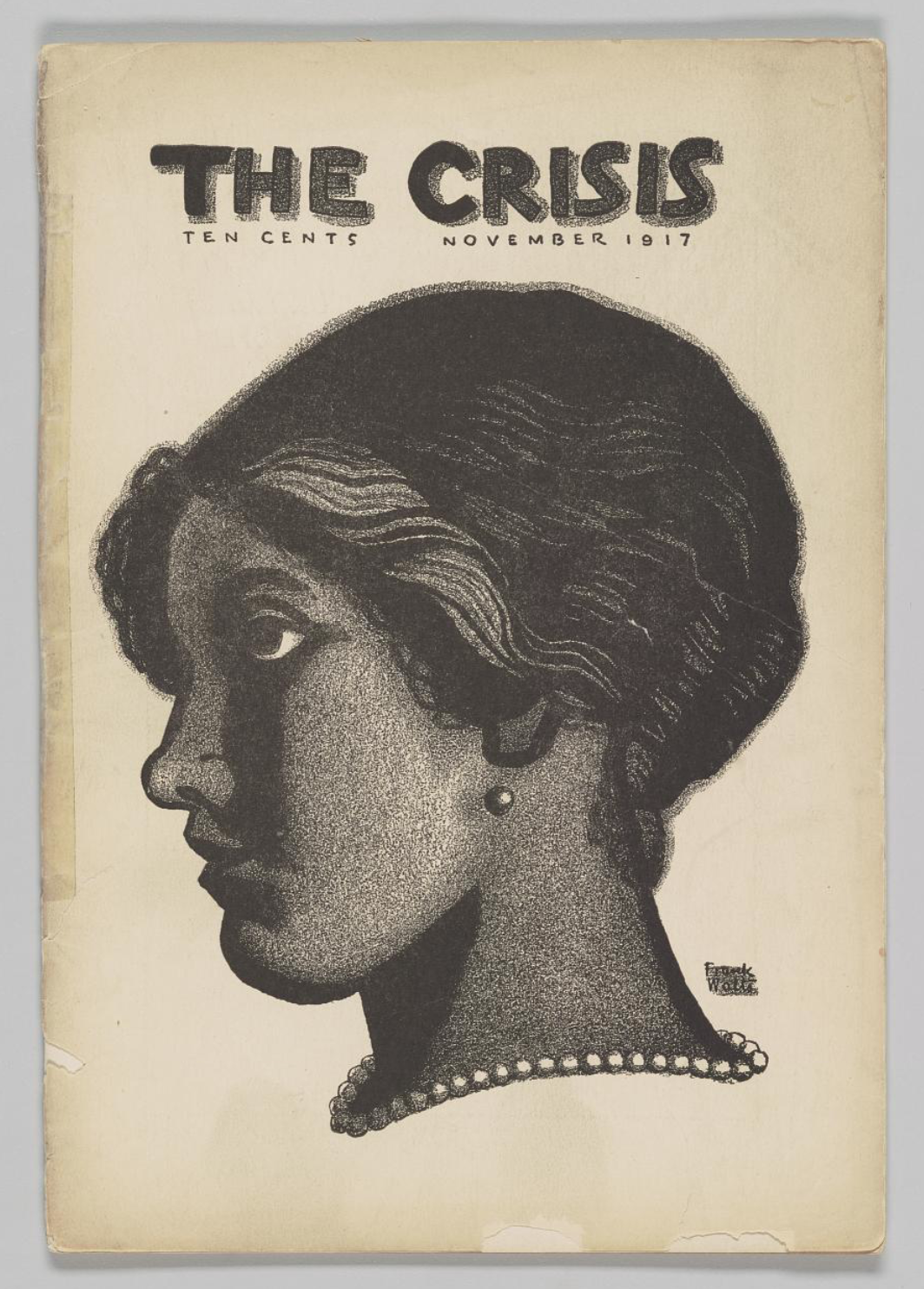

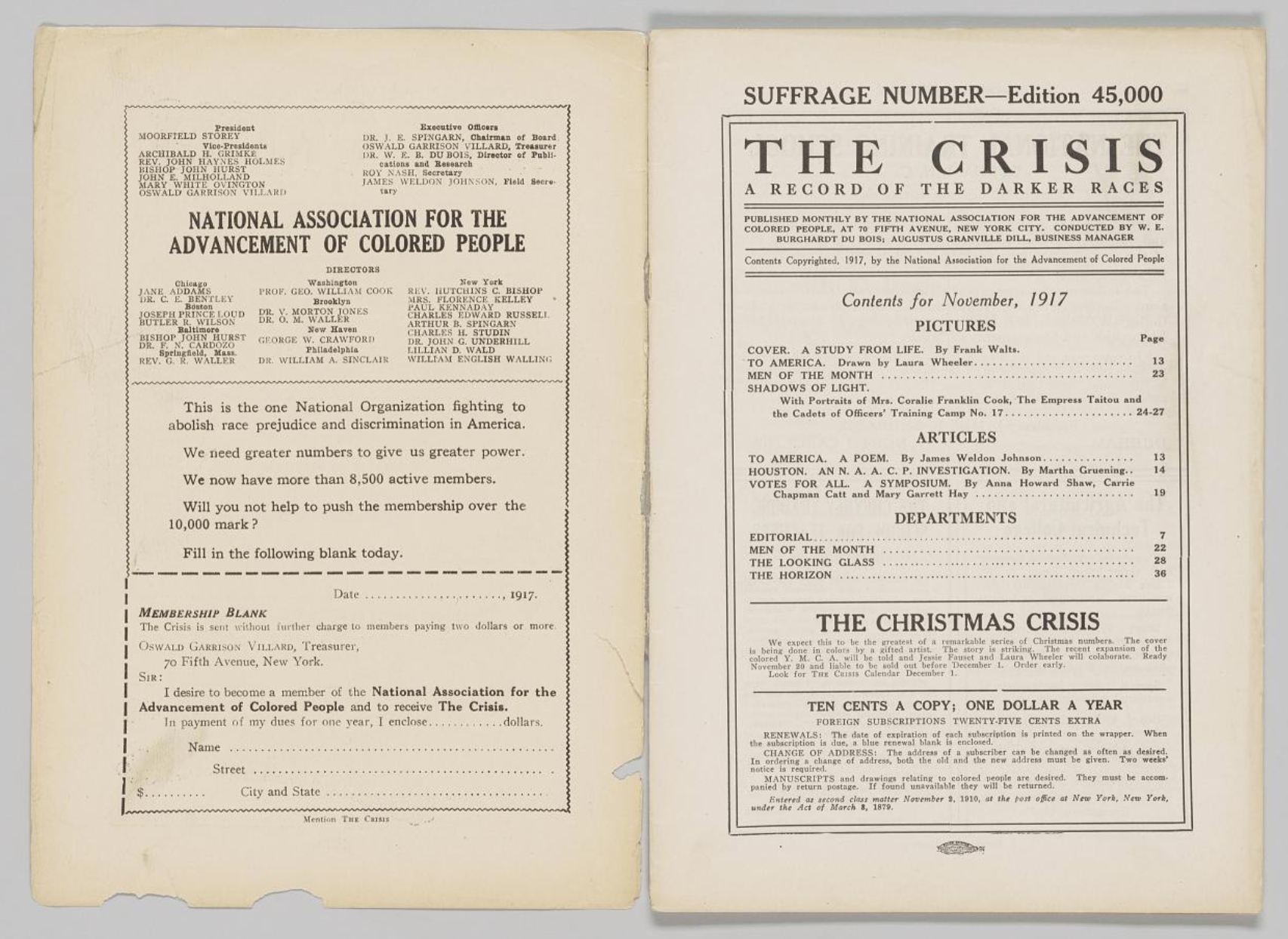

Three years later, in 1917, Johnson joined the staff of the NAACP, the civil rights organization founded only eight years earlier, as a field secretary. It was a job that time and time again sent him south to investigate Jim Crow and Ku Klux Klan violence, frequently to depart only after he’d laid the groundwork for a local chapter of the organization.

The Crisis magazine was the organization’s journalistic outlet, and it was on its pages that Johnson reported to the world what he observed and experienced on assignment.

His poetic voice was apparent in his report after visiting the site in Memphis of the public execution of Ell Persons, accused of but never tried for killing a 15-year-old white girl. It was Johnson’s first year in the job, and Person’s death had been an almost ritualistic spectacle:

“A pile of ashes and pieces of charred wood still marked the spot. While the ashes were yet hot, the bones had been scrambled for as souvenirs for the mobs. I reassembled the picture in my mind:

“A lone Negro in the hands of his accusers, who for the time are no longer human; he is chained to a stake, wood is piled under and around him, and five thousand men and women, women with babies in their arms and women with babies in their wombs, look on with pitiless anticipation, with sadistic satisfaction while he is baptized with gasoline and set afire. …

“I tried to balance the sufferings of the miserable victim against the moral degradation of Memphis, and the truth flashed over me that in large measure the race question involves the saving of black America’s body and white America’s soul.”

In 1920, Johnson rose to the top staff position in the NAACP, the first African American to hold the post of executive director. He stayed in that job for a decade and taught for a while at New York University, then returned to the South to teach literature and creative writing at Fisk University, the historically Black college in Nashville.

During the time that Johnson headed the NAACP, The Crisis secured a place as a premier journal of Black intellectual thought, a repository of fine writing and arts criticism, and a printed-word public square for discourse on issues of special interest to Black America.

As a critical component of the Black press in the time of lynching, it was in many respects a forerunner of the Sunday arts and opinion sections that would later be staples of white-owned dailies, but mostly beyond possibility for even the larger Black weeklies.

Even in his last days, he was adamant about how the lyrics he wrote should be seen and heard. “Johnson’s nurse said he was always careful to say that there can be one national anthem, and “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is a hymn,” said Morrisette, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro professor.

“It’s a hopeful song … that goes beyond Johnson to our more contemporary moment,” Morrissette said. “And what has happened to Black people throughout the nation, [who] over decades and decades have witnessed … the denial of just basic rights and recognition of humanity, of creativity, of invention, of political agency, anything you can possibly imagine.”

She referred specifically to the final words of the first verse:

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us.

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won.