By Khloe Quill

The Pittsburgh Courier that Robert L. Vann acquired in 1910 was a newspaper of humble beginnings. Its previous owner was a security guard at the H.J. Heinz Company food packing plant, and a self-published poet who sold copies for a nickel apiece.

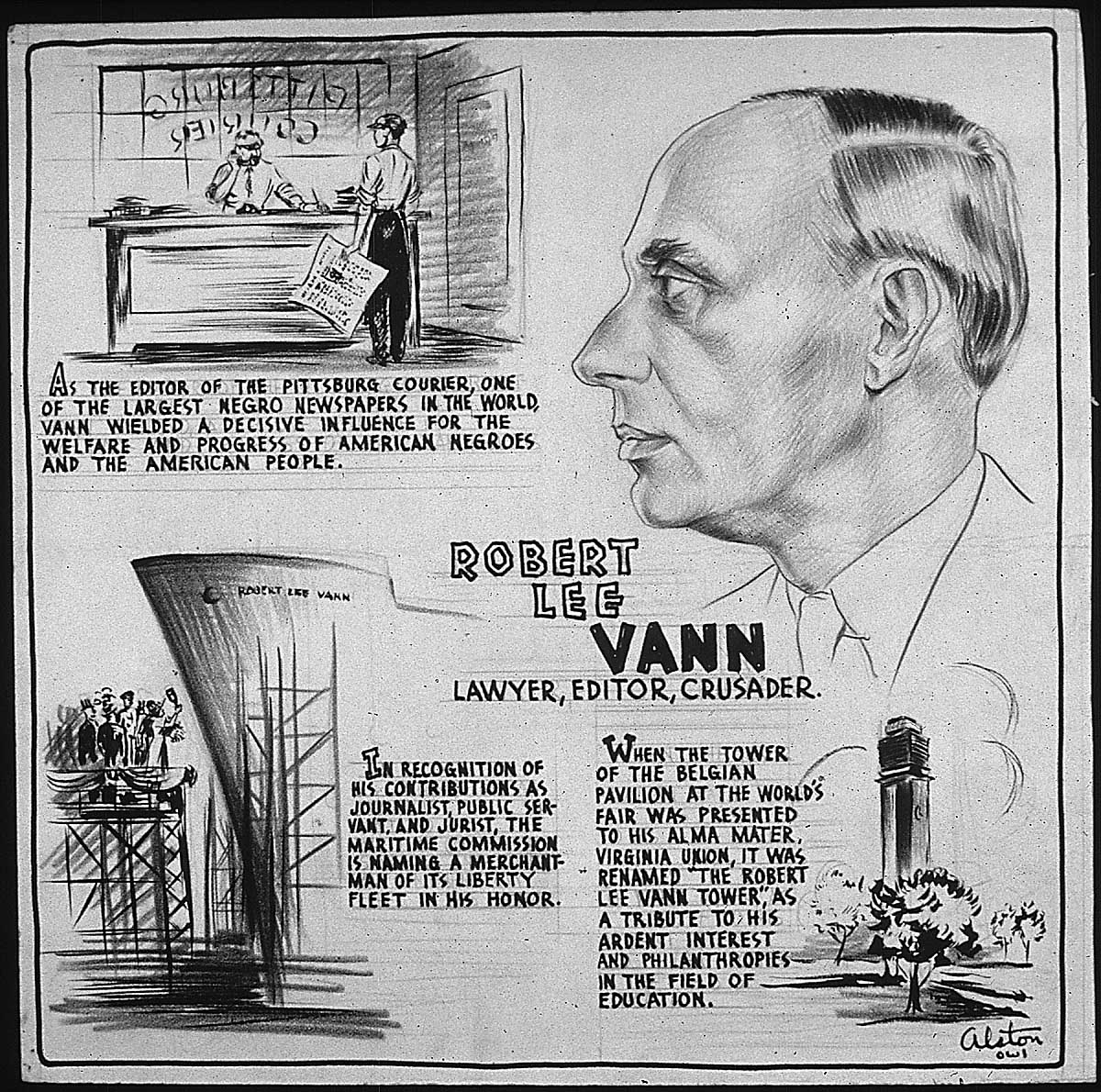

Using some spare space above a funeral parlor as his newsroom, Vann, one of only five Black lawyers in the city at the time, drew investors who had wealth and assumed a mission he would later describe as an effort to “abolish every vestige of Jim Crowism in Pittsburgh.”

That declaration echoed the intent of others going back to the nation’s first Black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, founded in 1827. Another of the Journal’s goals was to serve African Americans in ways that white newspapers were not.

This work is a collaboration of the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service at the University of Maryland, Morgan State University, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and the University of Arkansas.

The Courier reported on middle-class Black life in the city, including accounts of marriages, vacations, and the parties of prominent people. Vann enhanced the newspaper’s national and international coverage by joining the Associated Negro Press, the Black counterpart of the white news service of similar name.

He wrote editorials, mixed with columns and commentary from respected Black voices, and published original comic strips by Black artists and cartoonists, who celebrated Black life and were syndicated to others in the Black press.

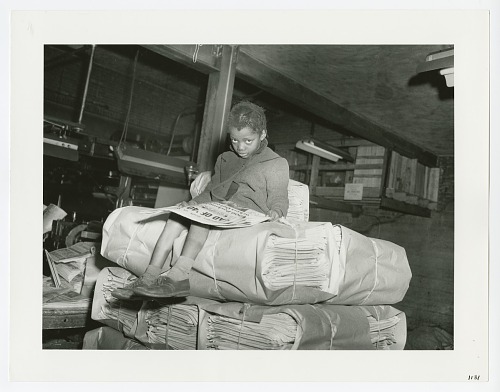

He used Black railroad porters as circulation men, taking copies to anywhere in the nation the rails took the trains.

By 1938, two years before Vann died, the Pittsburgh Courier was publishing four separate editions, and available in every state in the union, and internationally, as well. It had its own printing plant and could claim a circulation of 250,00—arguably the largest of any Black-owned newspaper at the time.

PRINTING HATE

EXPLORE ALL STORIES

The horrors of lynching, segregation, voter suppression and Jim Crow injustice were pushing African Americans out of the South. The North was pulling them in, especially the heavy manufacturing centers near the Great Lakes and along both sides of the Mississippi River, as it flowed south from Minnesota, down through the Arkansas and Mississippi deltas, and emptied into the Gulf of Mexico near New Orleans.

The Courier in Pittsburgh, the Michigan Chronicle in Detroit, The Call in Kansas City, the Call and Post in Cleveland, and The Argus in St. Louis were among the Black-owned newspapers that would come to serve Black communities close to those waterways, along with The Chicago Defender.

Robert Sengstacke Abbott founded The Defender in 1905 with an investment of 25 cents, a little more than $7 today. It would prove to be far more than a two-bit newspaper; instead, a model for Vann and others, to be known in short time as “The World’s Greatest Weekly.”

Abbott was born in coastal Georgia to enslaved parents. After his father died, his mother married a German immigrant. He attended Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Virginia, and later obtained a law degree. He launched the newspaper from his landlord’s kitchen.

The Defender became a journalistic poster for the benefits to be found up North—better jobs, better schools, better housing, and possibilities of professional careers.

Abbott himself was living proof of what his newspaper preached, becoming one of the first African American self-made millionaires in the United States.

Racial injustice of all types in the South received regular coverage in. The Defender. That was a staple of the Black press. But the paper also took up the cause of opposing racism and discrimination encountered by the new Black migrants in the North. “American race prejudice must be destroyed” was the newspaper’s mantra.

Its nine top goals included passage of a federal anti-lynching law, full voting rights for all Americans, and “opening up all trade unions to blacks as well as whites.” Also, “gaining representation in all departments of the police forces in the entire United States,” and “hiring black engineers, firemen, and conductors on all American railroads, and to all jobs in government,” in addition to “government schools giving preference to American citizens before foreigners.”

It was during the two decades after Vann and Abbott launched their newspapers that “the glory days of the black press began,” Larry Muhammad of the Louisville Courier-Journal wrote for Nieman Reports, the Harvard University periodical, in 2003.

“Back then, major papers usually wouldn’t even run African-American obituaries,” he wrote. “Black papers became the primary means of group expression and main community service outlet, reporting on job opportunities and retailers that didn’t discriminate, and covering charity events in uplifting society pages with big pictures of smiling, dignified black people enjoying each other’s company.

“There were bylined stories from America’s leading black activists and intellects—Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Langston Hughes in The Chicago Defender and W.E.B. DuBois, Zora Neale Hurston, Marcus Garvey, and Elijah Muhammad in the Pittsburgh Courier.”

The newspapers ran campaigns to urge their readers to patronize those who advertised on their pages, and also promoted black businesses, organizations and charitable efforts, as well as educational efforts and institutions, especially historically Black colleges and universities.

“In 1932, Courier publisher Robert L. Vann, Abbott and others steered black voters en masse to the Democratic Party, breaking traditional ties to the Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln and helping to elect Franklin D. Roosevelt,” Muhammad reported.

The courageous reporters, photographers and editors of the Black press and their determined and enterprising editors were the chroniclers and essential foot soldiers in the quest for African Americans’ freedom quest following centuries of enslavement in the United States.

The movement culminated in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Yet, in some ways, it was a bittersweet triumph, Muhammad wrote: “By the Black Power era, the formerly cutting edge medium was considered powerless.”

“The black press was considered, at best, a farm team for major dailies, which recruited top black journalists to cover the civil rights movement and eventually attracted readers and advertisers one considered the black press’s captive market,” Muhammad said. “Conventional wisdom by the 1980’s was that the black press, by doing such a bang-up job promoting racial equality, had made itself obsolete.”

Most of today’s Black-owned news operations, both in print and online, are local, and local news media of all types have been disappearing at what many believe is an alarming pace in the most recent years.

Yet obituaries for the Black press would be premature, said Denise Rolark Barnes, publisher of The Washington Informer and a past chair of the National Newspaper Publishers Association, which was founded in 1940 under the name the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association. .

As white-owned newspapers depart or cut back on coverage of communities of color, Black newspapers have new opportunities to gain subscriptions. “It is opening more doors,” Barnes said in an interview. “Our digital readership, from what we’ve been told, is predominantly white.

“Our paper moves in every neighborhood in the city, and so when it comes to community news, it puts an extra burden on us. …We are the local newspaper, and we’re not going to change who we are, our focus on the African American community,. But because we are a diverse community, we want more of our stories to reflect that diversity.”