BALTIMORE -- Veronica King strode to a scale in a West Baltimore church basement where two women holding measuring tapes were waiting. A minute later, she let out a shout and did a jig. King, 53, had dropped eight pounds in three months.

She couldn't wait to tell her daughter. "We'll be dancing tonight for real."

King is one of about 300 West Baltimore women who participated in Heart to Heart, a three-year, $775,000 pilot program started by St. Agnes Hospital.

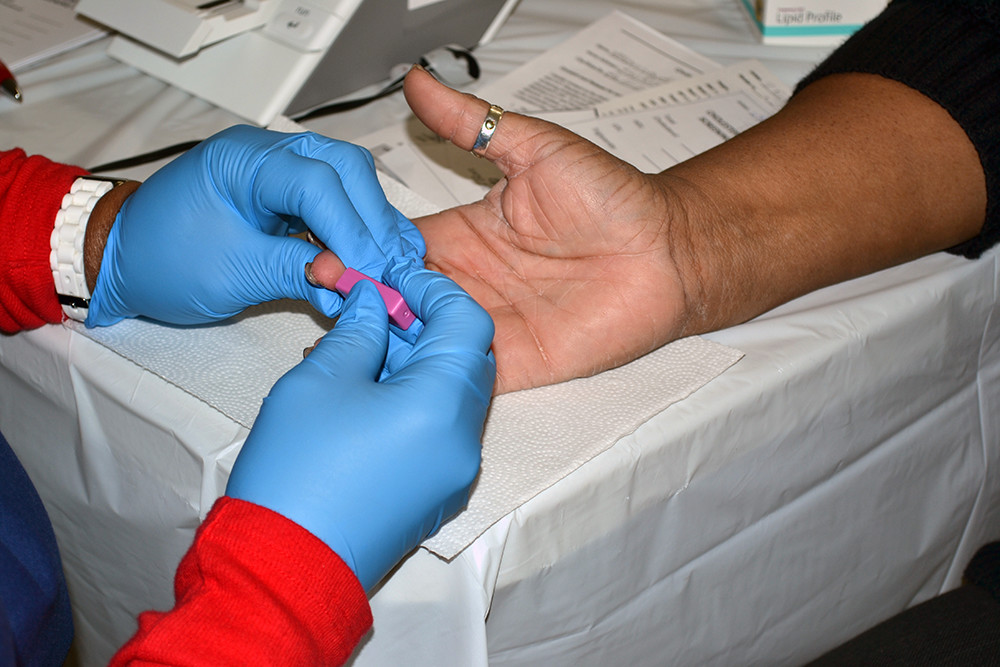

For three years, the program provided health screenings, health education and fitness classes at 13 churches and a mosque in the city. It offered women who met certain criteria a 16-week intervention program, where they worked with nurse practitioners to lower their cholesterol, weight, blood pressure and blood sugar.

But the program that helped King lose weight ended Dec. 31. Heart to Heart was a pilot program, one of many that have come and gone over the decades with the goal of improving the health of West Baltimore residents.

Pilots, by definition, are funded for a limited period, often to allow researchers to test a concept. But they are designed to end when the money runs out. And that, some public health researchers say, can be a problem.

"People feel like they've been working with a project and all of a sudden it's over," says Dr. Albert Wu, director of the Center for Health Services and Outcomes Research at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. "All of a sudden, they feel jilted.

"I think it's rare for pilot projects to be continued in part because in some cases they are tests to see if something works," Wu says. "Even if it does work, all you have is a demonstration."

Dr. Peter Beilenson, a former Baltimore health commissioner and former Howard County health officer, says there is no complete list of pilot programs because their creators -- nonprofits, foundations, hospitals and the city -- do not collaborate.

"The problems in the city are so large in volume," Beilenson says. Pilot programs work well for the people whom they target "but there's vastly more need than that."

Dr. Leana Wen, Baltimore City's health commissioner, agrees that many programs are working on the same issues without any awareness of one another.

"We need to make sure that those strategies are coordinated as a city," Wen says.

Heart to Heart and other pilots like it focus on preventative health care -- an effort to keep people healthy and stave off disease so residents don't end up in the hospital.

St. Agnes conceived Heart to Heart as a short-term program, and drug company AstraZeneca and the hospital's parent company, Ascension Health, funded it through grants.

Florence Mason, 63, who returned to Perkins Square Baptist Church last fall for her four-month follow-up exam, says Heart to Heart helped change her routine. She now walks the track at Edmondson High School regularly.

"I am thoroughly satisfied with the program," Mason says. "I hate to see it come to an end."

With Heart to Heart, St. Agnes administrators says they had hoped the churches and mosque would continue with and pay for the program once the pilot ended -- but so far none have.

Alicia Davies, Heart to Heart's coordinator at St. Agnes, says the hospital never envisioned supporting the program after its three-year trial.

"We didn't really have a maintenance program built in," says Elizabeth Kaylor, St. Agnes' director of grant management. "We thought, 'Great, we're going to go in. We're going to do this 16-week program.'...We didn't take it out far enough."

By conducting the screenings at the church, St. Agnes administrators expected members to create buzz about the program, and, they hoped, the beginning of a conversation about health and wellness in the community.

Dr. Joshua M. Sharfstein, associate dean for public health practice and training at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, says that "a lot of what contributes to health is outside of the health care system.

"Different programs should be tried," Sharfstein says, "and if they work, they should be continued."

But enthusiasm for Heart to Heart didn't seem to materialize.

At Macedonia Baptist Church, at W. Lafayette and N. Fremont avenues, with 300 active members, between nine and 12 women showed up for the screenings this year, says Sharon Webb, a parishioner who took part in Heart to Heart.

At Douglas Memorial Community Church, in Madison Park, associate minister Lottie Sneed says her church had a low turnout for the program.

“ I hate to see it come to an end.”

—Florence Mason, participant in pilot program on women's health

"We probably screened a little over 40 women to get some base data so they would know what was going on with them," Sneed says.

Wu, at the Hopkins School of Public Health, says that even short pilot programs can produce statistics that can be valuable to other programs.

"Even when things aren't successful, there are often lessons that are learned," he says. "Those lessons get incorporated elsewhere. More and more programs have a community advisory board, and that's just a thoughtful way of getting advice ahead of time for how to design something so that it's likely to be successful."

CNS reporter Nora Tarabishi contributed to this article.