PERRYVILLE - With a $5,000 grant from the town of Perryville in 2012, April Sumpter added a cobblestone walkway and flower beds around the brightly painted pillars at Box Car Avenue Ice Cream.

“It just brightened the place up,” said Sumpter, the ice cream shop’s owner.

The improvements wouldn't have been possible without the grant, and the grant wouldn’t have been possible without revenues from Hollywood Casino Perryville, which sits a few miles from the ice cream shop on the outskirts of town.

The Town of Perryville received $1.76 million from casino revenues last year. That money is a merely a tiny fraction of Maryland’s multi-million-dollar gambling industry. But to Perryville, a rural community of 4,392, it represented more than 30 percent of the town’s budget. They used the money to hire police officers, repair sewer mains, plan renovations for Town Hall and design a building to replace the double-wide trailer that serves as the police station.

The windfall was one of the results of legalization of casinos in 2008 and expansion of gambling in 2012. The revenue doesn’t just flow to the state. It benefits the communities around the new gambling emporiums too.

Perryville is home to the state’s first casino, which opened in 2010, two years after a referendum green-lighted the facilities — and, after the first year, it seemed to have hit the jackpot.

Yet as more casinos in the state have opened, drawing business away from Perryville, the grant money is already drying up — highlighting a trend that researchers project will continue as the fifth and sixth casinos come to Maryland.

“So many of the counties did not want casinos in their backyard until they saw the impact of the local casinos, and now every county in the state wants a casino, and that’s what’s cutting the revenue,” Sumpter said. “Not everybody can have a casino. It’s just that simple. And that’s what’s cutting the grant money.”

How gambling came to Perryville

There are no flashing lights advertising blackjack or slot machines on Broad Street, Perryville’s main road. Instead, the railway theme of Box Car Avenue Ice Cream is a recurring motif: “Perryville” is spelled out in huge letters on the railway track that cuts over the road outside Town Hall, and signs advertise the Perryville Railroad Museum in the train station across the street, the last stop on MARC Train’s northbound Penn Line.

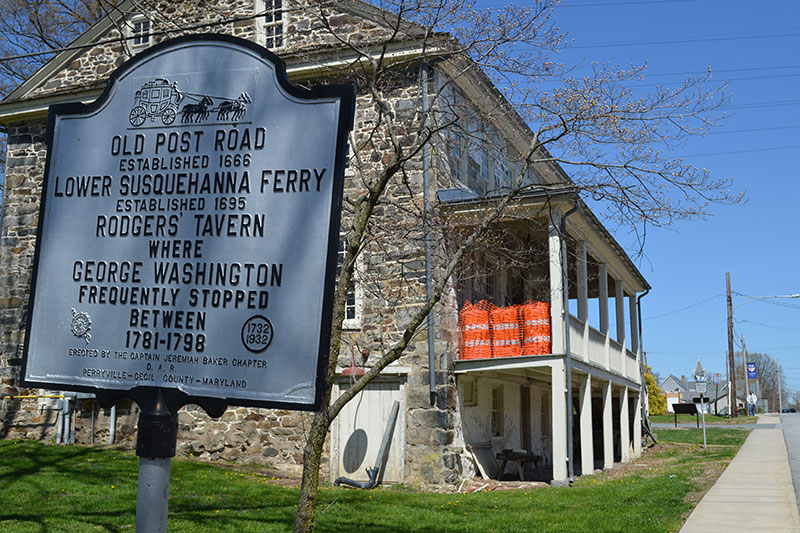

Sitting between Baltimore and Philadelphia on the northernmost tip of the Chesapeake Bay, Perryville has always welcomed travelers. Near the end of the Revolutionary War, it was one of George Washington’s favorite resting spots. He would stop at Rodgers Tavern, a building on the National Register of Historic Places that the town acquired in 1993. Nowadays, more than 80,000 people cut through the edge of town on Interstate 95 every day.

It is those modern commuters between Baltimore and Philadelphia that the state hoped to attract when it designated casino locations. The 2008 legislation required that one of the five original locations for a casino be in Cecil County, within 2 miles of I-95.

Penn National Gaming submitted a proposal for a site in Perryville, which the state accepted in October 2009. The state received a $9 million licensing fee and the promise of a $77.6-million-dollar investment in real estate and construction from Penn National.

Hollywood Casino Perryville was the first and only casino operating in the state until the Casino at Ocean Downs opened in Worcester County in January 2011. There were initially no bidders for the site in Allegany County, and the developers in Baltimore and Anne Arundel County both delayed their openings.

Since the gambling law required the Cecil County casino to be close to I-95, it sits on the far edge of Perryville’s town limit surrounded by nothing but parking lots. The only other building in sight is Perryville’s water tower.

“It has not changed the character of the town, primarily because of its location,” said Perryville Mayor Jim Eberhardt, who has been supportive of the casino since gambling legislation was under consideration in 2008. “We saw it as stimulus for the town.”

Local impact grants

That stimulus has taken the form of jobs and grants. The Hollywood Casino is the second-largest employer in Perryville, behind only the Perry Point VA Medical Center. The casino employs 390 people, 240 of whom work full time, according the casino’s human resources department.

Perryville’s portion of the casino’s earnings is the town's largest source of revenue, topping both real estate and corporate taxes.

Maryland’s gambling law requires 5.5 percent of slots revenue from all casinos in the state to be divvied up proportionally to communities that host casinos, so the more money Hollywood makes, the more money Perryville receives in grants.

As the first casino to open in Maryland, Hollywood Casino Perryville got off to a lucrative start. The casino raked in more than $2 million in its first four days of operation, and average monthly revenues were $9.4 million for the first full 18 months the casino was open.

Under an agreement between Perryville and Cecil County, the town receives 35 percent of the local impact grants generated by the Hollywood Casino, with the county retaining 65 percent. Perryville was seeing monthly checks of nearly $150,000 for the first year and a half the casino was open.

“The first thing we did was hire a couple of police officers, and buy some new cars,” Eberhardt said. The town also spent about $20,000 on a fingerprinting system for the police force and $135,000 on building and site plans for a new police station to replace the double-wide trailer.

Lt. Allen Miller of the Perryville Police Department said construction on the new police station was supposed to start this year, but logistical problems involving water and sewer have pushed the project back. He said although the local impact grants are helping fund the new station, the project would move forward even without the additional revenue, because the expanding police force needs more room.

“You can see what we’re working out of -- a double-wide mobile office. So it would definitely go ahead because of the expansion of the town...it would take place without a doubt,” he said.

So far, $103,000 is set aside for the police station, not including the $135,000 already spent on design plans. Estimates put the price of a new station at $1.8 million, though the final plans must be completed before the cost is nailed down, according to Town Administrator Denise Breder. Perryville also stashed away $458,000 for the Town Hall, which is estimated to eventually cost $4.5 million.

The local baseball league was another beneficiary of the grant money. Clint Logan, the vice president of the Perryville Little League, said casino money paid for 80 percent of the cost of a $17,000-dollar tractor and put $10,000 toward a zero-turn mower.

“They’ve been really generous,” said Logan, as he painted lines on the baseball diamond’s infield to prepare for an upcoming game. “We’re working up plans within our board right now to set which big ticket items we need each year.”

The board’s plans include expanding the concession stand and flipping the baseball field around so that home plate faces Town Hall and the Susquehanna River.

Perryville also used the money to fund two grant competitions, up to $25,000 to local charitable organizations and as much as $10,000 for business owners like Sumpter in the town center.

Sumpter said the local impact grants have helped the town, but the casino hasn’t affected daily life in Perryville. Because of the casino’s location, it doesn’t bring traffic to local businesses. Casino-goers can come and leave without ever spending money in Perryville.

They only “come here when they’re lost,” she said.

Here comes competition

Hollywood Casino’s quick starting pace slowed when Maryland Live!, the state’s third casino, opened in June 2012 near the more heavily populated and monied stretch of interstate between Baltimore and Washington. After making more than $10 million the month before Maryland Live! opened, Hollywood Casino saw revenues of less than $7 million by July 2012.

Maryland Live!’s opening prompted Bill Hayles, former general manager of Hollywood Casino Perryville, to write a letter to Maryland state Sen. Nancy Jacobs in August 2012 notifying her of the casino’s intention to return 400 to 500 machines to the state because of declining revenues.

“We are making this adjustment now in response to the impact of Maryland Live! as well as in anticipation of Baltimore’s opening,” Hayles wrote, “as we expect that Baltimore will have an even greater impact on Perryville’s revenues than Anne Arundel has thus far.”

Hayles’ successor, Matthew Heiskell, has few qualms about the new casinos in Baltimore and Prince George’s County.

“We’re going to be concerned any time a competitor opens up near you,” Heiskell said, “But I do believe it won’t have the dramatic effect that Maryland Live! did.”

The Baltimore casino will be the closest to Perryville, about 10 miles closer than Maryland Live!. If the additional competitor cuts into Perryville’s profits, the casino will consider a further reduction in slot offerings, Heiskell said.

The Hollywood Casino Perryville’s revenues rebounded in March 2013, when table games and 24-hour gambling debuted in the state. Yet afterward, revenue continued to dwindle throughout the year.

The slots revenue in January 2014, $5.3 million, was the lowest in any month since the casino opened. Under the 2012 gambling expansion, none of the revenue a casino receives from table games such as roulette or craps goes toward local impact grants until 2017, when they will begin to receive a 5 percent cut. Instead, the casino operator keeps 80 percent of the money, while the remainder goes to the state’s Education Trust Fund.

The funding for the downtown revitalization grants and the grants for charitable organizations was cut in half in Perryville's 2014 budget. Perryville’s original three-year plan produced in 2011 projected $2.81 million in grants. Instead, it received $1.76 million.

Property taxes, which have been cut every year since the casino opened, may go back up as the money declines, Eberhardt and Breder said. Savings for the new Town Hall and police station haven’t even reached 10 percent of the buildings’ respective costs, so the projects will need other sources of financing.

“We’ve been a little conservative,” Eberhardt said, adding that the town has not taken on any debts it expects future slot revenues to cover. “What I tell everybody is, if it goes away tomorrow, it’s been good. We just need to always keep in the back of our minds: Don’t count on this.”

Who’s Next?

Perryville’s revenues were poached by Maryland Live!. Maryland Live!’s is next.

The Horseshoe Baltimore Casino, opening this summer, is run by Caesars Entertainment, while MGM’s proposal for a massive complex just outside Washington is slated to open in 2016.

While the casinos are expected to generate an overall increase in state gambling revenues, the money won’t be evenly distributed. The older casinos are expected to lose business to the new — and, like Perryville, their surrounding communities will see a decrease in local impact funds.

Maryland Live! is projected to see the biggest drop in revenues from expansion, but every existing casino’s revenues will suffer each time a new venue opens its doors in the state. Maryland Live!’s revenues are projected to drop 19 percent, about $130 million, by 2016, and another $94 million by 2019, according to a 2013 Cummings Associates report. The other casinos in the state stand to lose $137.4 million of revenue when MGM comes to National Harbor.

For Anne Arundel County, that means local impact grants would drop by more than $12 million, according to projections. The county was awarded $20 million in 2014, a small share of the its $1.3 billion operating budget. But the grants funded the county police department’s addition of 18 officers and the county fire department’s staffing, equipment and maintenance at the three stations closest to the casino.

They also paid for the Anne Arundel County Community Action Agency’s mental health service for youth and families, the Villages of Dorchester Homeowners Association’s soil erosion control project and a new heating and air system at Meade High School.

John R. Hammond, of Anne Arundel County’s budget office, said that although the county budgeted $20 million in local impact grants for fiscal 2014, it would realize only $18 million, due to the decrease of slots play at Maryland Live! and the increase in table game play, the revenue from which does not now go toward local impact grants.

The county will allocate the remaining $2 million from its general funds to ensure all grant recipients receive the money they were awarded, Hammond said.

The county has already tempered its expectations going forward. When the Horseshoe Baltimore Casino begins to eat away at the casino’s business, Hammond said he expects local impact grants from Maryland Live! will drop to $15 million for fiscal year 2015.