The Green Bowl, a two-year-old food truck, stops in Fells Point every Friday during lunch hours. Capital News Service photo by Sissi Cao

The Green Bowl, a two-year-old food truck, stops in Fells Point every Friday during lunch hours. Capital News Service photo by Sissi Cao

BALTIMORE - When David Chapman decided to open a bright green food truck selling healthy meals in large bowls two years ago, he had a lot less competition on Baltimore’s streets.

“I was just tired of having a boss,” Chapman, 34, said of his decision to leave his career as a technician to start The Green Bowl, dishing out Bibimbap, a Korean-inspired rice dish, and other favorites to a loyal customer base.

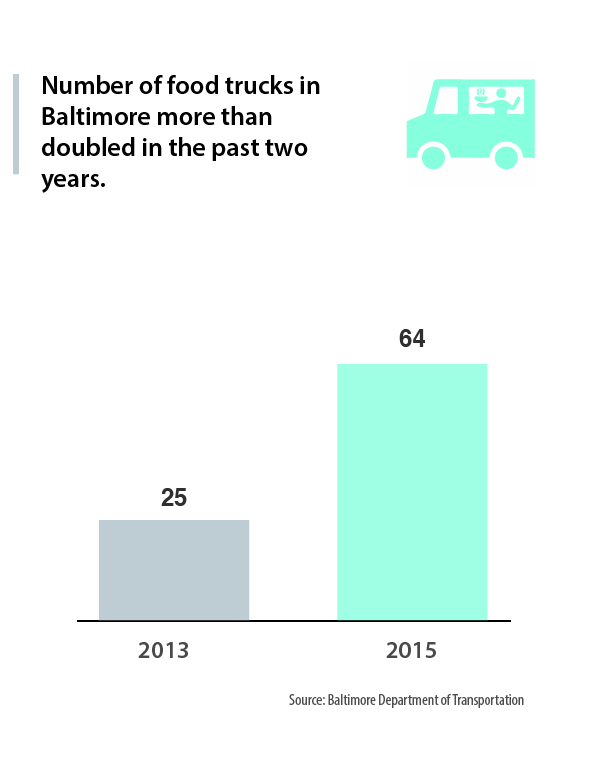

Two years later, the number of food trucks roaming Baltimore in search of customers has more than doubled from 25 to 64, according to city transportation department data analyzed by Capital News Service.

Food truck owners say they expect their ranks to continue to grow, despite outdated street vending laws governing food trucks that could hamper future expansion in Baltimore.

Today, it’s possible to get a Greek lamb burger, Indian tandoori, a lobster mac and cheese cone and a hand-crafted caramel latte from food trucks that roam the city. The Green Bowl, for example, appears on the stone-paved Thames Street at Fells Point every Friday around lunchtime, where Jimmy McNeely often grabs a meal.

“I come here mainly for the convenience, because it’s right next to my office. I either bring lunch from home or come here,” said McNeely, 25, who works at Morgan Stanley, a two-minute walk from The Green Bowl’s spot on Thames Street.

Ashley Ridgeway, 26, a security staffer at Morgan Stanley, said she has taken to eating lunch from food trucks because of their “creativity,” which sets them apart from standardized fast food offerings.

“They offer food that’s not on the menu in traditional restaurants,” Ridgeway said. “I had never bought lunch from food trucks until I began working here about a year ago. Now I’m a big fan.”

Ridgeway has tried four different food trucks that come to Fells Point on different days. Her favorites: those that sell barbecue and burgers, like The Smoking Swine on Tuesdays or Gypsy Queen Cafe on Fridays.

“I’m not a calories counter, so I’m not too concerned about the healthfulness of these food,” she laughed.

The food truck movement began about ten years ago in Los Angeles, led by a Korean barbecue truck called Kogi, according to the Associated Press. In the ensuing decade, food trucks have spread to cities large and small, becoming a critical part of the dining landscape.

Drew Pumphrey, a civil engineer turned food truck owner, normally serves 120 to 150 customers during lunch on a typical weekday from his barbecue truck, The Smoking Swine.

“It’s been far more profitable than we initially thought,” Pumphrey said, noting that he only needs to serve 60 people to turn a profit for the day.

Food trucks fill the sweet spot of “convenience food,” in between the two traditional eatery categories, fast food and restaurants. They serve tastier food than fast food chains, but at a faster pace than most sit-down restaurants, making it particularly appealing to the young and busy.

David Pulford, owner of UpSlideDown Dave, a three-year old barbecue truck in Baltimore, said most of his customers are urban professionals between 25 and 40.

“A lot of baby boomers still don’t quite get the idea. But some late baby boomers are very accepting [of] food trucks,” Pulford said.

As food trucks become more popular, the gap between existing restaurant regulations and the needs of mobile eateries is becoming more apparent in Baltimore and other U.S. cities.

In March, the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University published a case study on current food truck regulations in four U.S. cities, including Washington, D.C.

“Municipalities are being forced to revisit these regulations as issues arise over competitiveness, parking, sanitation, property and sales taxes, and proximity to brick and mortar businesses,” wrote Jessica Huey, the author of the case study report.

The “proximity law”, which prohibits food trucks from operating within 300 feet of any restaurant, is common in many cities, including Baltimore. Because hungry customers tend to congregate in restaurant-dense areas, the law puts food trucks at a disadvantage.

Sean Burnett, a senior inspector at the city transportation department who manages street vending, said the proximity law was originally created to protect both food trucks and restaurant owners from competing with each other.

“During the creation of the legislation, the focus was becoming more … friendly,” to small restaurants that are more vulnerable to competition than large restaurants, Burnett wrote in an email.

Food truck owners, however, are not convinced that food trucks and restaurants compete for the same customers.

“There is no proof that restaurants are negatively affected by food trucks at all. Food trucks sell a different league of food. It’s completely different from a restaurant,” Pumphrey said. “What we are in competition with are brown-bag lunches -- whether people bring lunch to work or not.”

Restaurant owners see it differently. “I don’t see any disparity in demographics between food truck consumers and restaurants,” said Tony Minadakis, owner of Jimmy’s Famous Seafood, a casual dining spot in downtown Baltimore.

For the last two years, the restaurant has also operated a food truck that tours the city every day. “We use this food truck more as a marketing tool than a profit generator. So far it has helped bring more people to our restaurant,” Minadakis said.

To accommodate the needs of mobile food vendors, many cities have created “food truck zones” – parking spots that are designated for food trucks. Prince George’s County passed a law in October that created 12 “food truck hubs” in the county. Under old laws, food trucks were only allowed to do business at festivals and other one-day events.

Finding a parking spot during lunch hours is still a pain for vendors. The designated spaces are frequently filled. And if they park in a regular space, they run the risk of violating the proximity law by parking within 300 feet of a restaurant.

Baltimore first created food truck zones in 2011. In June 2014, the city council passed a bill promising to create more zones. But after almost 18 months, that promise has yet to be fulfilled.

In some cases, vendors have seen existing food truck parking spots vanish.

Chapman from The Green Bowl said there used to be a food truck space at the crossing of E. Pratt Street and Commerce Street, until a Shake Shack opened in February. The city removed the food truck space during construction. But after Shake Shack opened for business, the food truck spot wasn’t replaced.

“It’s what the city wants to do. In some cases, it’s obviously that it’s what the restaurant wants,” Chapman said.

The city transportation department said they had not removed any food truck spots due to new restaurants opening. But they have been forced to remove spots because of construction and utility maintenance work. Burnett said construction around the Shake Shack location is still ongoing, and the city is looking for a replacement spot for food trucks.

Baltimore currently has about 60 food trucks and nine 50-foot food truck spots plus a food truck park downtown, according to city records. A 50-foot spot can generally hold two food trucks. The trucks can also use regular street parking spaces as long as they comply with the proximity law.

Besides restaurants, food trucks are also restricted from parking within two blocks of schools, city markets, and football and baseball stadiums on game days.

The spot on Thames Street in Fells Point The Green Bowl favors is a regular street parking space -- but there’s no guarantee it will always be available. Last month, The Green Bowl circled around for an hour and eventually had to move to another place three miles away.

Very sorry Fell's point, but after circling the block for an hour, we cannot find any parking. Our future here is uncertain...

— The Green Bowl (@bmoregreenbowl) November 6, 2015“Now there are very few spots in town that are any good and worth parking at. It’s a mess.” Chapman said.