For Maryland’s juvenile lifers, the hope of leaving prison emerges

Howard Center for Investigative Journalism

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland — For two decades Maryland governors have followed a tough-on-crime policy that denied parole to youths who had been sentenced to life. Gov. Larry Hogan is now softening that policy, allowing parole for three inmates convicted as juveniles.

Hogan’s shift comes in the face of U.S. Supreme Court rulings that sentencing a minor to life without parole was cruel and unusual punishment. The Democratic governor who initiated the policy of denying parole to anyone sentenced to life now calls it "a very bad mistake." And Hogan, R, is facing a federal lawsuit brought by the ACLU charging that the practice is unconstitutional.

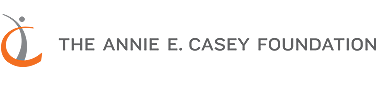

Juveniles in Maryland had been receiving life sentences with the possibility of parole as early as 11 years into the sentence. But because four consecutive governors had refused to release them, today more than 300 such inmates — some now in their 50s and 60s — sit waiting to see what Hogan’s decision on the three paroles means for them.

Hogan declined an interview request.

Chris Mincher, the deputy legal counsel for the governor’s office, told Capital News Service that Hogan "talked about this issue in his original campaign, and it’s something that he gives serious attention to."

All three men granted parole by Hogan already have left prison, state corrections officials said.

Robert Davis, 54, had served 37 years for first-degree felony murder and handgun charges. Navarus Mayhew, 42, served 24 years for first-degree murder, robbery and gun charges. And Shawn Delco Goodman, 42, served 27 years for first-degree murder and robbery charges, according to Maryland Parole Commission records.

The families of their victims could not be reached for comment on the releases.

Hogan approved paroles for two of the men and allowed Davis’ to happen without his signature.

Until the Hogan administration, parole hadn’t been granted for any lifer — adult or juvenile — since Gov. Parris Glendening, D, effectively ended it with his “life means life” stance based on the tough-on-crime political climate of the era.

Glendening now regrets that decision and has publicly and repeatedly advocated a change in state law to remove the governor from the parole process.

"I made a mistake," he said in a recent interview with "PBS NewsHour" correspondent John Yang. "It was a very bad mistake in the sense that it impacted people, it impacted subsequent administrations, but it was a mistake. And I think it's important to acknowledge."

(Video edited by Athiyah Azeem | Capital News Service)

In the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court case Miller v. Alabama, sentencing a minor to life without the possibility of parole was deemed cruel and unusual. A 2016 suit, Montgomery v. Louisiana, declared that the 2012 ruling be applied retroactively, effectively eliminating the sentence for juveniles.

In 2016, the ACLU of Maryland filed a federal class action lawsuit against Hogan on behalf of the Maryland Restorative Justice Initiative and three incarcerated juvenile lifers. The three juvenile lifers in the ACLU suit are not the 2019 parolees.

The state had argued that gubernatorial commutations — executive orders to shorten a sentence — over the years had met the Supreme Court’s standard. But advocates said commutations are more like winning the lottery than earning parole.

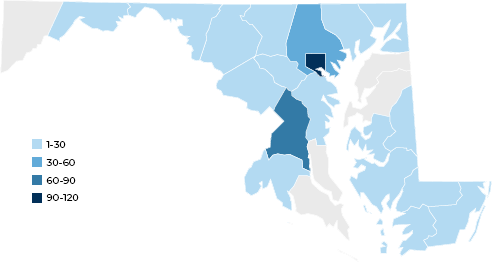

| Administration | Juvenile Paroles | Adult Paroles | Juvenile Commutation | Adult Commutations | Medical Paroles | Total Releases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glendening (1995-2003) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Ehrlich (2003-2007) |

0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| O'Malley (2007-2015) |

0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Hogan (2015-Present) |

3 | 8 | 4 | 17 | 4 | 36 |

The lawsuit states that Maryland’s process of juvenile lifer parole denied "meaningful opportunity for release," therefore violating constitutional protections against cruel and unusual punishment.

"More than 300 people in Maryland are serving parole-eligible life sentences for offenses committed as children," ACLU Maryland attorney Sonia Kumar said in a press release. "After holding nearly 200 parole hearings prompted by a lawsuit filed by juvenile lifers wrongly denied release, Maryland is paroling three people. During the same period, Pennsylvania has paroled nearly 200."

The ACLU suit is pending.

Maryland is one of only three states that requires a governor’s signature to grant parole in the case of life sentences. Governors granted paroles under this system until the 1990s, when rising crime rates spurred more stringent policies and public demonization of prisoners.

Crime and punishment became hot issues in Maryland in 1993, when "model inmate" Rodney Stokes — on work release, the last step before parole — killed his former girlfriend and himself.

In the last 24 years, seven juvenile lifers have been released from prison after their sentences were commuted.

Gov. Robert Ehrlich, R, commuted two juvenile lifers and paroled none.

During Democrat Gov. Martin O’Malley’s eight years in office, he commuted the sentence of one juvenile who had been given a life term; he did not parole any juvenile lifers.

Hogan had commuted the sentences of four juveniles as of late October before allowing the parole of the three juvenile lifers in November.

Maryland legislators have tried to remove the governor’s hand from the state’s parole process in recent years.

"Of all the powers you want, to be involved in that kind of decision is not one of them," Glendening said. "The issues are too emotional and too political to put it on the desk of someone who is going to turn around in a few months, a year and run for election. And it almost asks for political decisions on something that should not be political."

In 2017, parole reform legislation that would dismiss the governor from the process was passed in the state House of Delegates, but failed to advance in the Maryland Senate. This past session, a similar bill made little headway in either chamber.

State lawmakers are turning their eyes to 2020 — some with the hope that more advancement could be made this time around.

The bill’s former House sponsor, Delegate Pam Queen, D-Montgomery, said in an interview with Capital News Service in October that there are plans for similar legislation in the upcoming session, and is looking to the Senate and its new president, Bill Ferguson, D-Baltimore, to determine what will or won’t make it through.

Lawmakers are looking to have the 2020 iteration of the bill sponsored by a member of the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee. According to the chief of staff for Sen. Delores G. Kelley, D-Baltimore County, a previous sponsor of the legislation, they are aiming for the bill to include new measures to account for family and victim concerns.

In 2018, Hogan signed an executive order addressing juvenile lifers specifically, requiring that the governor weigh the same elements as the Maryland Parole Commission when considering parole, as well as the inmate’s age at the time of the offense and any signs of maturity or transformative rehabilitation.

Attempts to find and contact attorneys, family members of victims, and parolees have not been successful, or individuals have declined to comment.

Parole is recommended to the governor by the Maryland Parole Commission. After a hearing and risk assessment, the commission may send a parole recommendation to the Office of the Governor. Once received, the governor has 180 days to confirm, allow its approval without a signature, or deny it. If a prisoner is released to the community, they are under the supervision of a parole officer. Violation of the terms of an individuals’ parole can lead to reincarceration.

Medical parole is a release condition that occurs when an incarcerated individual is so chronically ill that they are no longer considered a danger to others. At this point, they are released to the care of a family member, hospital or hospice facility, and are returned to prison should their health recover.

Commutation is a form of clemency granted by the governor that results in a changed or shortened sentence. In commuting a sentence, the governor has some discretion over when and under what conditions a prisoner is released, unlike with paroles.

Pardon is a process, following an application, of executive clemency under which the governor absolves the grantee of guilt for a crime and exempts them from penalties for those crimes. Formerly convicted individuals can apply to have portions of their criminal record expunged and restore some of their rights.

* Story originally published by Capital News Service on November 22, 2019.

READ MORE: The Victims’ Side

READ MORE: Meet The Juvenile Lifers

About This Project

This work is a collaboration among the University of Maryland's Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service and the PBS NewsHour.

Credits

Web design and development: Camila Velloso

Reporting and writing: Athiyah Azeem, Victoria Daniels, Hannah Gaskill, Dominique Janifer, Lynsey Jeffery, Jamie Kerner, Lauren Perry, Sara Salimi, Delon Thornton, Emily Top and Camila Velloso

Data analysis: Riin Aljas, Hannah Gaskill and Camila Velloso

Video: Athiyah Azeem, Hannah Gaskill, Dominique Janifer, Lynsey Jeffery, Jamie Kerner, Lauren Perry, Sara Salimi, Delon Thornton, Emily Top and Camila Velloso

Graphics: Hannah Gaskill, Ally Tobler and Camila Velloso

Project editors: Kathy Best, Tom Bettag, Karen Denny, Marty Kaiser, Adam Marton and Sean Mussenden

Audience engagement: Alex Pyles

Top photo: Capital News Service

Funders

Support for this project comes from generous grants from the Scripps Howard Foundation, the Annie E. Casey Foundation and the University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism.