COLLEGE PARK, Maryland -- From selecting the stories that pop up in our Facebook feeds to deciding whether we’ll get a loan, artificial intelligence algorithms make countless choices that influence our lives.

Now, they’re permeating courtroom judgments. In some jurisdictions, “risk assessment” algorithms help determine sentences for those convicted of crimes.

And increasingly, similar algorithms are being used in the beginning stages of the criminal justice process, where they have a hand in deciding where a person will spend their time before trial -- at home or in jail. For those arrested, this decision could be the difference between keeping a job, housing or custody of their children.

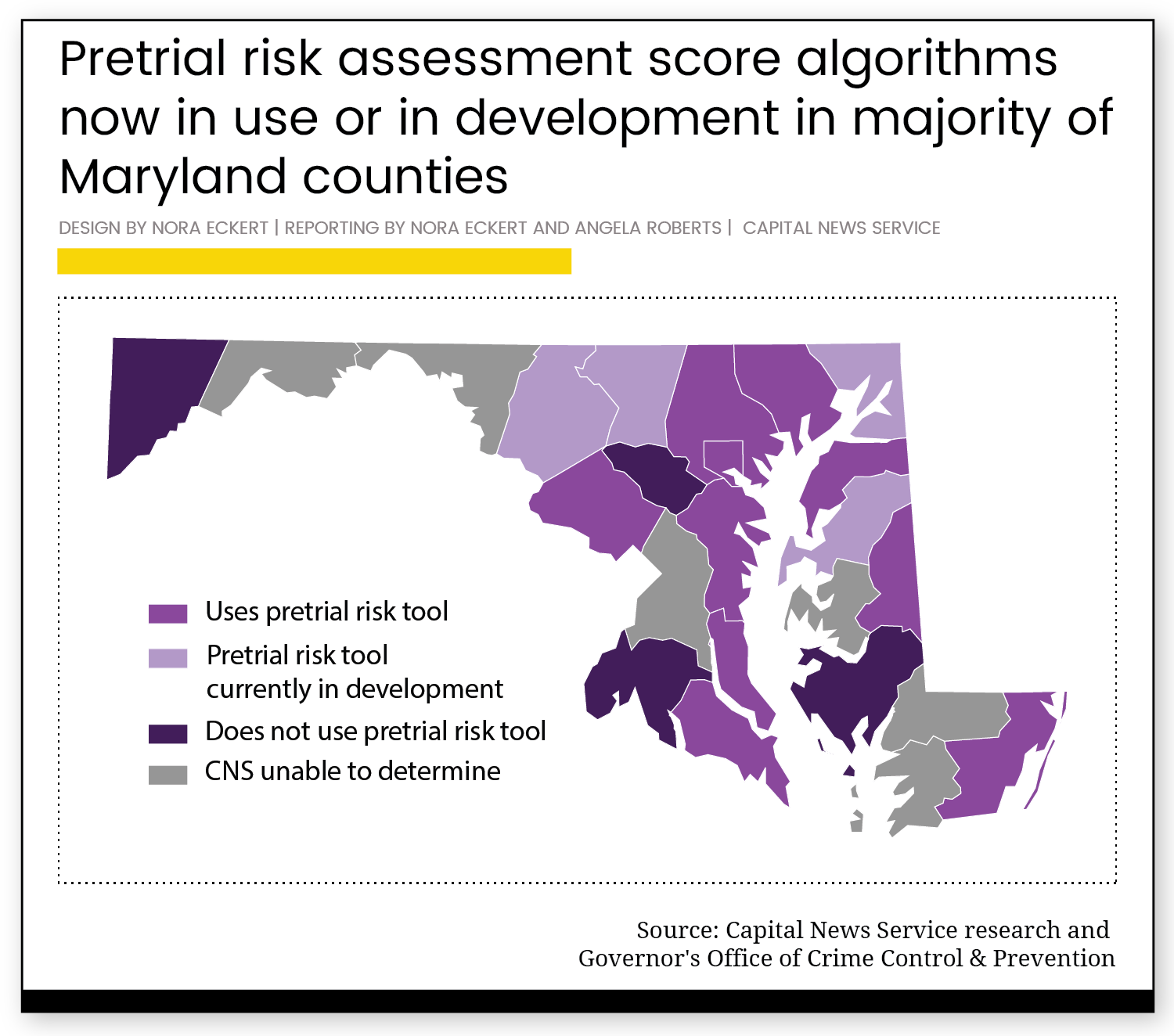

Following a national trend, a flurry of counties across Maryland have recently taken steps to incorporate statistical considerations into pretrial detention rulings, Capital News Service found. While court officials said this move inserts a sense of objectivity into an otherwise subjective decision, some criminal justice reform advocates are left with concerns.

In the last three years, at least four of Maryland’s 24 counties have started calculating “risk scores” for defendants based on an algorithm that indicates their likelihood of reoffending or failing to show up to trial if released from jail, joining the six counties that did so prior to 2015, Capital News Service found

And at least four other counties will soon start using scoring mechanisms, also called pretrial risk assessment tools, Capital News Service found.

These tools condense aspects of a defendant’s criminal history and background in a single score that bolsters the information judges use to make bail decisions. And studies have shown that they reduce the number of people detained before trial.

Indeed, Montgomery County saw their pretrial detention population decline by 30 percent after implementing a tool, according to Robert Green, director for the county’s Department of Correction and Rehabilitation.

And Kent County Warden Herbert Dennis said his jurisdiction experienced a similar decrease after adopting a tool and adding pretrial services last year -- an important development, he said, considering the potential cost of detainment.

“A lot comes from getting incarcerated,” Dennis said. “[Being released] actually helps people keep their jobs and still function with their families and keep from losing their housing.”

But if a tool isn’t built or tested properly, pretrial reform advocates like Cherise Fanno Burdeen worry that it could potentially start handing out scores that inaccurately designate defendants as high risk -- a determination that could be used to needlessly keep them in jail before trial.

This concern is especially salient for minorities being scored by a tool that considers factors that may discriminate based on race.

“It’s very rare we’d be talking about whites overrepresented in high [risk] categories,” said Burdeen, CEO of the Pretrial Justice Institute. “It’s predominantly the concern that people of color will be over-categorized or they will appear in more severe [risk] categories.”

In this case, rather than work to eliminate discrimination in pretrial judgments, a tool could perpetuate racial bias already embedded in the criminal justice system.

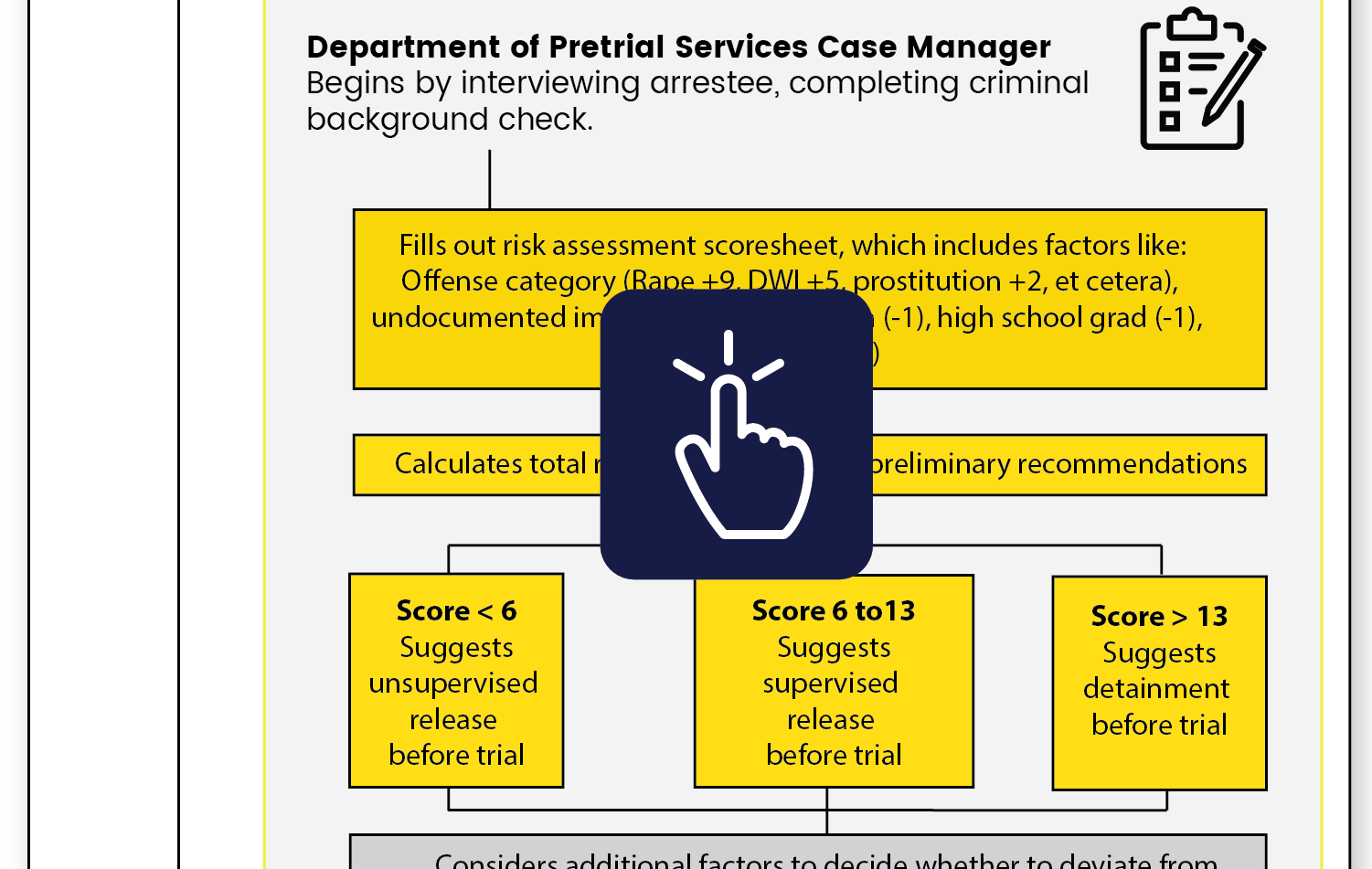

Pretrial risk assessment tools are part of an involved process that requires a lot of human decision making. Consider what happens when someone gets arrested in St. Mary’s County, which introduced a tool in 2015.

If the defendant isn’t immediately released by a court commissioner or can’t make the bail assigned to them, they move on to the next phase: a criminal history check and an in-depth interview with a pretrial case manager.

This case manager uses the information to fill out a pretrial risk assessment scoresheet:

Accused of a very serious offense like rape? That’s plus nine points. Were you convicted of DWI in the previous decade? That’s another five points. Failed to show up for trial before? That’s plus one or two points. Graduate from high school? Subtract a point. Have a job? Subtract another point. Are you a woman? That’s another point off.

The case manager tallies a total risk score.

A high total score -- more than 13 -- triggers a recommendation for a defendant to stay in jail pending trial. Defendants who score less than six are recommended for release without supervision. Everyone else is suggested for pretrial release with some form of supervision, whether it be an ankle monitoring bracelet or drug testing.

The preliminary recommendation suggested by the tool is not final. A case manager can issue a final recommendation that deviates from the path suggested by the tool, in some designated cases. For instance, managers can recommend that defendants with identified substance abuse issues be detained even if their risk scores are less than 14.

And it is ultimately up to the judge to make the final call on whether a defendant will get out of jail before trial.

The point values paired with specific questions on the scoresheet weren’t picked at random.

Rather, these values -- or weights -- were determined by a computer using a form of artificial intelligence called “machine learning classification.” Machine learning classifiers are statistical models that identify hidden patterns in data, then use the patterns they have learned to carry out a specific task.

Classifiers keep spam out of our email inboxes by identifying suspicious emails and routing them to our junk folders. And they are at the core of many pretrial risk assessment tools.

To build the tool, data scientists first pool information from a group of defendants who already came through the court system and were released from jail before trial.

They know whether the defendants in this pool were rearrested before trial and whether they showed up to court for trial. The information also covers details from their backgrounds -- their gender, age, criminal history and more.

Then, the data scientists set a classifier loose on the data.

The classifier examines the background information collected about defendants. Then, it finds correlations -- or, to put it another way, relationships -- between those background information factors and whether someone failed to appear at court or were rearrested after their release.

Not all relationships are the same. Some factors do a better job of explaining why someone might not show up for trial, and are assigned higher point values.

The weighted factors are put onto a worksheet a pretrial case manager can use. This worksheet allows the manager to use something they know about a new defendant -- background information -- to determine something they don’t know -- the defendant’s risk of reoffending or failing to show up to trial if released.

In 2007, Montgomery County used data from their local population to build a custom pretrial risk assessment tool. Over the past decade, this tool has quickly spread across the state.

In 2015, St. Mary’s County adopted the tool Montgomery County developed, making minor changes to the risk classifications of two factors. Since then, at least three other counties in Maryland -- Caroline, Kent and Worcester -- have picked up the tool from St. Mary’s. And at least two others -- Cecil and Queen Anne’s County -- are in the process of doing so, Capital News Service found.

The rise of these tools in Maryland follows a national push to reform the bail system, which studies have found punishes low-income communities. Last year, the Maryland judiciary put forth new guidelines that ban judges from assigning defendants crippling sums of money at bail hearings to prevent their release.

State officials like Del. Erek Barron (D-Prince George’s County) said adopting pretrial risk assessment tools furthers the mission of this rule change.

“The wider goal is that you want to make sure decisions aren’t being made based solely on money,” Barron said. “So the tool is just one piece in the judge’s pocket, so to speak, to try and make an evidence-based decision as to whether someone is a flight risk or a danger to the public.”

Even if a tool’s scoresheet does not add or subtract points based off a defendant’s race, it could still rely upon factors that leave people of color at a statistical disadvantage, Capital News Service found.

Take Baltimore City, for example, which introduced a pretrial risk assessment tool in 1966. For more than 50 years, the tool penalized defendants for having previous arrests, even if those arrests did not result in convictions. Black people in Baltimore are arrested at a rate disproportionate to their population in the city.

In 2017, 63 percent of the city’s population was black, according to the Census Bureau. But in the same year, 83 percent of people arrested were black, according to a Capital News Service analysis of Baltimore crime statistics.

In an effort to reduce racial bias, Robert Weisengoff, executive director of Baltimore’s pretrial services, said the city will introduce a new tool in February that will no longer consider previous arrests that did not result in a conviction.

“We saw that that particular question could raise an issue of racial bias,” Weisengoff said. “I didn’t want the instrument to even have a hint of racial bias to it.”

Montgomery County and the jurisdictions that use a modified version of the tool they created continue to rely upon factors, like employment and education level, that could be biased against people of color.

Montgomery County’s tool drops a point from the risk scores of defendants who are employed. But the unemployment rate for black Marylanders was about four percentage points higher than for white Marylanders at the start of 2018, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Judges in Maryland are required to consider a defendant’s employment status when making bail decisions. They’re not, however, required to consider a defendant’s level of education.

Still, the Montgomery County tool subtracts a point from a defendant’s score if they have a high school degree or higher. Last year, the high school graduation rate for white students was seven percentage points higher in the county than it was for black students, according to the Maryland State Department of Education.

Capt. Deborah Diedrich, acting commander of the St. Mary’s County corrections division, said the tool they use is not racially biased, even though it considers these factors.

"We do not discriminate, and I do not feel the assessment tool does at all,” Diedrich said.

But the county does not track metrics that prove the tool provides fair and accurate scores across different demographics.

“We don’t measure it,” Diedrich says, referring to racial bias. “We just know it’s fair.”

The captain emphasized that race is not mentioned in the tool’s scoresheet.

Yet for pretrial reform advocates like Zina Makar, this does not negate the possibility that a tool could discriminate based on race.

“Simply saying you’re not taking into account race does not mean your tool is race neutral,” said Makar, co-director of the Pretrial Justice Clinic.

Through a process called validation, jurisdictions can test their tools to make sure they are still calculating accurate risk scores for defendants -- and treating people of different races fairly.

Experts vary on how often jurisdictions should validate -- some say every five years, some say every two -- but they agree it’s something that should happen regularly.

This recommendation extends to both counties that built their own tools (like Montgomery) and to those that picked tools up from other jurisdictions (like St. Mary’s), said Edward Latessa, who helped create and validate Ohio’s risk assessment system.

A county might start using a tool before they have the data available to test it, Latessa said. But he added that as soon as a county has collected enough data to validate, which could take up to a year, they should do so.

This process had added importance, since Latessa said it also ensures a tool isn’t producing racially biased outcomes.

For this reason, Burdeen called it “ethically irresponsible” for a county to neglect testing its tool.

Montgomery County is now in the middle of revalidating their tool for the first time since developing it 10 years ago. The county would have taken steps to revalidate sooner if they had seen warning signs like a significant increase in people being rearrested when released before trial or failing to show up at court, Community Corrections Chief Angela Talley said.

Still after using the tool for 10 years, “it’s appropriate to go back and make sure we’re not missing anything or that anything’s changed for us,” she said.

St. Mary’s County cited the high price tag of validation -- which can cost anywhere from $30,000 to $50,000 -- as a reason contributing to their decision to wait to test their tool. They also determined internally that they would need to collect 3-5 years of data before validating.

But even if a county can’t raise the funds needed to cover the cost of validation, Burdeen said there are other ways to test for racial discrepancies in results.

She suggested that counties keep data on the defendants who are released -- including any conditions they must follow to stay out of jail and whether they violated these conditions -- and sort it monthly by race to compare results across groups.

Montgomery County doesn’t keep any data on the race of defendants who go through their system. Instead, they monitor the number of people who are rearrested or fail to show up to trial when released to make sure the tool is working correctly.

Kent County doesn’t track this information either. But Dennis said officials at each stage of the pretrial process -- including public defenders, the state’s attorney and those who conduct interviews with defendants -- regularly check in with one another.

“We all communicate and make sure this thing is actually working,” he said. “Right now, it seems like everything’s okay.”

At the bail hearing, the risk assessment tool recommendation is only part of what a judge considers when making a decision. According to Maryland rules governing pretrial release, judges are also required to take into account several other factors, including the information presented by prosecutors and defense attorneys and the defendant’s history of appearance at court proceedings.

And this should be the case, even if the tool was created and implemented correctly, policy experts like Makar said.

“You really need to know the person and that comes by hearing what defense counsel has to say. There has to be some level of discretion in making that judgment call,” said Makar.

Pretrial officials like Talley said they are comfortable with their supporting role.

“We are there to assist and provide information. It is up to the judge to make the final decision about whether the person should be released or not,” Talley said.

However, some experts believe that tools are essential in decreasing bias in a judge’s decision, since they compile a number of factors from a defendant’s background and criminal history in a single score.

Without the recommendation from pretrial services, “[the judge] will select the pieces [of information] that matter to them the most and they will judge the person in front of them from a completely subjective place,” Burdeen said.

Besides the judge’s ruling, there are several things a risk assessment tool can’t control.

A tool can’t change policing practices or racial discrepancies in the job market or education system. And pretrial services can’t be expected to eradicate all unfairness in the criminal justice system without cooperation from judges, attorneys and police.

But, according to Burdeen, while a tool cannot nullify these discrepancies, a well-tested, properly built one has the power to reduce racial bias in the pretrial system.

“It is an incredible case of schizophrenia,” Burdeen said. “The conversation has to be that we recognize that bias. We’re trying to use a tool to create a less biased decision-making framework.”