TUCKER, Arkansas — There were reasons from the start to doubt Charlie Vaughn’s story that he and three other people raped and murdered a 78-year-old woman in 1988.

As Vaughn pleaded guilty in court, he stumbled over details. Without prompting, he couldn’t name all the people he had said were with him. He was confused about the charge to which he was pleading guilty.

Vaughn was 24 but couldn’t read or write. He told the judge he’d been tested to see if he was mentally competent. The judge didn’t ask for the results. He accepted Vaughn’s guilty plea and sentenced him to life in prison.

The other three people were convicted of murder a year later, largely on the basis of Vaughn’s guilty plea and testimony.

More than 20 years later, the case unraveled. One of the four admitted to committing the crime — alone. Two had their convictions overturned.

But Charlie Vaughn, now 51, remains in prison here, a man with cognitive disabilities who, in pleading guilty to a crime he did not commit, gave up nearly all his legal rights.

More than 9 of 10 convictions in the United States result from plea bargaining. The criminal justice system could not function if every defendant sought a trial. But the system has flaws. A nationwide team of journalists has identified 137 cases in which defendants pleaded guilty despite significant evidence of their innocence.

There are many reasons. But at heightened risk are defendants like Vaughn, who have mental disabilities that may make them unable to understand the nature of the proceeding, or to assist their attorneys — the standard set by the U.S. Supreme Court for whether defendants are competent to stand trial, or to plead guilty.

No one knows how often defendants with mental disabilities plead guilty, and certainly not how many of those might be innocent. But more than 95 percent of cases end in pleas. And about 2 of 10 prisoners and 3 of 10 jail inmates reported having a cognitive disability, according to a 2011-2012 Bureau of Justice Statistics survey.

The team identified four such cases among the guilty pleas by suspects who likely were innocent.

In 1960 the U.S. Supreme Court first laid down guidelines for when a defendant is competent to stand trial.

It is not enough for a judge to find that the defendant knows where he is, and when, and has “some recollection of events.” The test, the court wrote, “must be whether he has sufficient present ability to consult with his lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding — and whether he has a rational as well as factual understanding of the proceedings against him.”

In 1993, the Supreme Court established that the test used in trials — a defendant’s ability to both understand and assist his lawyer — also applies to guilty pleas.

“The whole process is supposed to be designed to make sure there is an assessment if the defendant is unfit, and then everything grinds to a stop,” said Mark Heyrman, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School who specializes in mental health law. “If a defendant is unfit, there cannot be a trial and there cannot be a guilty plea.”

But that standard has limitations. Jerry Frank Townsend was 27 in 1978 when police officers picked him up in connection with the rape of a pregnant woman on a Miami street. He was described as having the mental capacity of an eight-year old. Nevertheless state psychiatrists ruled him competent.

Under questioning by police, Townsend did not admit to just the rape. He began admitting to six unsolved murders around Miami-Dade and Broward Counties dating back to 1973.

Townsend had a tendency to want to please those who questioned him, his lawyer, Dennis Urbano, said in a recent interview.

He “could function, but he was susceptible to saying anything you wanted him to say,” Urbano said. “I got him to confess to the Lindbergh kidnapping just to prove that point. He obviously did not know who that was, nor did he have anything to do with that.”

Experts say the desire to please is common among people with mental disabilities and makes these individuals more prone to false confessions.

The developmentally disabled, wrote Richard A. Leo, a law professor at the University of San Francisco who studies police interrogation practices, “tend to have a high need for approval and thus are prone to being acquiescent. They have adapted to their cognitive disability by learning to submit to and comply with the demands of others, again especially those of authority figures.”

That makes them more likely, in the first instance, to confess to police; and later, once they confess, to then plead guilty in court, experts say.

Townsend was tried and convicted of first-degree murder for two 1973 killings for which the key evidence was his confession.

Townsend then had a choice: Plead guilty to more crimes he did not do, or risk more convictions and the death penalty. By accepting a plea deal, Townsend would avoid Death Row.

“Jerry wouldn’t be here today if he hadn’t pleaded guilty,” Urbano said.

Townsend pleaded guilty to two murders that occurred years earlier in Miami, and he pleaded no contest to two more murders in Broward County.

He was sentenced to life in prison.

Eighteen years later, at the urging of the mother of one of the victims, authorities discovered that the DNA on one of the bodies belonged not to Townsend, but to a serial killer named Eddie Lee Mosley.

Four years after that, in 2000, Mosley’s DNA was found on other victims whom Townsend had confessed to killing. In 2001 Townsend was cleared of the remaining murders and released after almost 22 years in custody.

No mental competency hearing was held before 20-year-old Sammy Hadaway pleaded guilty to attempted robbery in Milwaukee in 1996, after testifying he had taken part in a robbery-murder with another man, Chaunte Ott.

Hadaway had severe cognitive and intellectual disabilities caused by cerebral palsy and seizure disorders since birth.

“I don’t think there was any factual dispute that these disabilities rendered him with competency problems,” Steven Wright, co-director of the Wisconsin Innocence Project and Hadaway’s post conviction lawyer, recently said of Hadaway.

He also said, however, that Wisconsin holds a high standard for incompetence. “It’s unlikely that a judge would have ruled him incompetent in this type of case,” he said.

Police were investigating the murder of a 16-year-old runaway, Jessica Payne, when a jailhouse informant pointed them to Hadaway and Ott. Payne’s body had been found behind an abandoned building, her throat slashed and her clothing mostly removed.

The police picked up Hadaway and questioned him over two days, before he told officers that he and Ott had walked behind a house, where Ott raped and then killed Payne.

A jury convicted Ott of first-degree murder and attempted robbery after Hadaway and the original informant testified against him. After testifying, Hadaway pleaded guilty to attempted robbery, and received a five-year sentence.

Chaunte Ott was released from prison in 2009, 13 years after his conviction, after DNA tests of Jessica Payne’s body excluded Ott and Hadaway, but matched DNA found on the bodies of two unsolved murders in North Milwaukee.

Ott was in custody when those murders were committed.

By then Hadaway had completed his sentence. But when he sought to overturn his conviction, a Milwaukee Circuit Court judge sided with the state. He ruled that Hadaway committed perjury by falsely accusing Ott in his 1996 trial, so he was not entitled to relief.

In August 2018, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals reversed that ruling.

Barry Scheck, co-director of the New York-based Innocence Project, said defendants who plead guilty have a more difficult path to prove their innocence for several reasons.

They may have entered the guilty plea before critical evidence surfaced. But in guilty plea cases there is typically no trial record, so it can be difficult to prove whether evidence discovered later would have made a difference.

On top of that, Scheck said, courts like finality. Courts “are reluctant to ever allow you to set aside a plea agreement that you entered into voluntarily.”

Most lawyers don't learn anything about mental illness or disabilities in law school, said Heyrman, the University of Chicago Law School expert, and so may fail to recognize their clients’ disabilities and raise the issue.

In the case of Edgar Coker, 15, accused of raping a 14-year-old girl in Virginia, his court-appointed defense attorney never bothered to gather school records or consult with experts to establish his mental deficiencies.

Coker suffered from “very limited intellectual capabilities,” according to a teacher and special education coordinator’s affidavit submitted after his guilty plea. But Coker’s mother said his lawyer told her the teen’s mental limitations were not relevant to defending him.

According to court records, the lawyer, Denise Rafferty, told the boy and his family that the detective on the case said Coker had confessed. She told them there was DNA evidence. It was probable, she said, that he would be convicted as an adult and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Rafferty later contended that she did not say there was DNA evidence. She did not respond to several requests for comment.

The teenager had a grim choice: Plead guilty and be sentenced as a juvenile, or go to adult court and face potentially decades in adult prisons. Coker took the deal.

In August 2007 he pleaded guilty and was sent to the Hanover Correctional Center for an indeterminate juvenile sentence. As important, he was listed on the state registry of sex offenders, a lifetime designation.

He remained in Hanover even after the girl recanted her accusation. The courts denied Coker’s efforts to vacate his guilty plea. Finally in 2009 he was released on parole.

But being released only complicated Coker’s legal struggle; lower courts found that once he was free and had completed parole, they no longer had jurisdiction to even consider his petition to reverse his guilty plea.

The legal battle went up to the Virginia Supreme Court, which in 2012 ruled that Coker’s petition could be considered because he was still on probation at the time the petition was filed.

Meanwhile, his status as a sex offender loomed over his family. According to his mother’s affidavit, she once came home from work to find a note on her door saying, “We don’t want a rapist living in our neighborhood.”

On another occasion, Coker was arrested at a football game at Orange High School, which he attended and graduated from, for being a sex offender on school grounds. He was jailed for five hours before his bail was posted.

Coker was now represented by the University of Virginia Innocence Project. His new attorneys built their case for overturning his guilty plea on allegations that his defense lawyer, Rafferty, inadequately represented him.

It turned out that not looking into Coker’s school records and mental capacity was not Rafferty’s only oversight.

In post-conviction proceedings, Rafferty said Detective Gerald Lloyd told her Coker confessed directly to him to breaking into the girl’s house, going up to her bedroom and raping her.

But Detective Lloyd testified he did not tell Rafferty that Coker had broken into the house or forced himself on the girl. Lloyd testified that Coker contended he had consensual sex with her.

In an interview, Coker said he never had confessed to a crime.

According to testimony, Rafferty never learned that the interview with Lloyd was recorded, and never listened to it.

The girl’s mother agreed in affidavits that her daughter had a history of false accusations.

In February, 2014, Virginia Judge Designate Jane Marum Roush ruled that Rafferty had failed in her representation of Coker, and found a reasonable probability that those failures caused Coker to be wrongly convicted. His conviction was overturned, and his name was removed from the Virginia sex offender registry.

Jeffrey Aaron, a psychologist, evaluated Coker following his conviction in 2007, and found that he has borderline cognitive abilities. Speaking generally, Aaron said, such deficiencies limit a defendant’s ability to understand the issues around entering a guilty plea.

“When you get to a plea bargain,” Aaron said in an interview, “a decision to accept a guilty plea and give up all your rights or many, most of your rights away, you've got to weigh a lot of different things simultaneously.”

Aaron said that the kind of cognitive limitations that Coker had would leave defendants more vulnerable to falsely confess to police, as well as more vulnerable in court proceedings.

"They're going to be more vulnerable in the course of the legal proceedings themselves to just sort of blindly go on and do what they're told or not assert themselves,” he said.

In a recent interview, Coker, now 27, said he thought he had no choice but to plead guilty. “I think it was a trap game,” he said. “They wanted a conviction. It was never fair. I never had a fair shot.”

Police Chief Ronnie Poole found a grisly scene when he arrived at the home of Myrtle Holmes in Fordyce, Arkansas, in 1988, according to trial testimony.

Relatives had reported the 78-year-old woman missing. Poole found the carpet and couch in her living room spotted with blood, and a broken knife blade on the floor. Her bedroom was ransacked, her bed covered in blood. A trail of blood led police to the garage, where they found her body in the trunk of her car.

With no arrests, frustrated family members engaged a private investigator, who agreed to a $5,000 reward if he solved the case. Eventually, he later testified, two informants told him that Charlie Vaughn and Reginald Early were involved in the murder.

On March 16, 1991, the county prosecutor charged Vaughn, Early, and a third man, John Brown, with murder.

Vaughn had been a special education student until he dropped out of high school. At age 24, he could neither read nor write. Authorities repeatedly questioned him, and on March 24 he confessed in the presence of his attorney and his mother, naming Early, Brown, and another person, Tina Jimerson, as participants in the crime.

The next day, March 25, he walked into Circuit Court Judge John M. Graves’s courtroom and pleaded guilty to murdering Holmes, in exchange for the charge against him being reduced to first-degree murder from capital murder.

Graves noted that he had granted a motion for Vaughn to take a mental examination, and asked Vaughn if he had done so. Vaughn said he had, though he could not recall the doctor’s name.

The judge did not ask for the test results, and Vaughn’s lawyer, Robert Remet, did not intervene.

Instead, Graves began addressing Vaughn about his plea, to assure that Vaughn understood the legal rights he was giving up by admitting guilt.

At times, the transcript indicates, Vaughn was confused, as when the judge read the charge: “You did commit or attempt to commit a felony and in the furtherance of the commission of that felony, you or one of the accomplices caused the death of Myrtle Holmes, under circumstances manifesting extreme indifference to the value of human life, and the felonies that were involved were one of either rape or robbery. To that charge, how do you plead, guilty or not guilty?”

Vaughn asked, “To robbery?”

“Not to robbery,” the judge replied. He repeated the full charge with different wording and Vaughn nodded, according to the transcript.

The judge then asked Vaughn to describe the night of the murder:

Vaughn responded that Jimerson drove him, Brown, and Early to Myrtle Holmes’s house that night, intending a robbery. While Jimerson waited in the car, the men broke in through a window. When Holmes woke up, Brown started beating her. The three men then raped her. Brown then stabbed and killed her, and he and Vaughn put the body in the trunk of her car.

Vaughn said he had written a statement for the police with the same information.

But again, Vaughn seemed confused or unsure of details. Where Holmes lived. What weapon was used to beat her. Asked if Holmes was conscious or unconscious when she was raped, Vaughn answered, “I think so, sir.”

Despite Vaughn’s confusion, Graves accepted Vaughn’s plea and sentenced him to life in prison for first-degree murder. “I’m sure that some governor somewhere down the road will reduce the sentence or commute it to a term of years,” he commented.

Both Graves and Remet died years ago. The prosecutor, Robin Wynne, now a justice on the Arkansas Supreme Court, did not respond to a request for comment.

A year after Vaughn’s guilty plea, Brown, Early, and Jimerson went on trial in 1992 for capital murder. The trial ended in a hung jury, after the state presented DNA evidence that excluded Brown and Vaughn as suspects in Holmes’s rape.

At a retrial, no DNA evidence was presented. The main evidence was Vaughn’s earlier confession implicating Jimerson, Brown, and Early, along with testimony from witnesses who claimed to have seen them together on the night of the murder.

On the stand, though, Vaughn said he could not recall the name of the victim. Nor could he remember having seen Brown, Jimerson, or Early anywhere except in the courtroom.

Asked about his plea agreement, Vaughn responded, “I was just going by what y’all said.” He added, “Y’all put words in my mouth.”

“When you say ‘y’all,’ what do you mean by ‘y’all’?” the prosecutor asked.

“The lawyer I had,” Vaughn said. His lawyer “had me say it all that day” so he would be prepared to recite the story at the plea hearing, he added later.

Vaughn said he was confused and feared the death penalty. He added that he could not write, so the reference in the plea hearing to him “writing” a statement could not be true.

Nonetheless, the jury convicted Jimerson, Early, and Brown of first-degree murder. Each received a life sentence.

Decades later, enough doubts had emerged about the convictions that pro bono attorneys began digging into the case.

In 2015, Karen Thompson, an attorney for the New-York-based Innocence Project representing Early, filed a motion seeking DNA testing on his behalf. But Early contacted her about something she needed to know: He had committed the robbery, assault and murder of Myrtle Holmes by himself.

The DNA was likely to incriminate him, he told his attorney. Vaughn, Jimerson, and Brown had had nothing to do with the crime.

Early told Thompson he wanted to go public with his confession to help the others, and signed a detailed affidavit.

The post-conviction attorneys also discovered a recorded confession that defense lawyers were never told about. An inmate in jail with Vaughn after his arrest said the sheriff offered him leniency if he would “get the guy to talk about the murder” and record the conversation.

Armed with Early’s confession and the withheld evidence, Jimerson and Brown were given post-conviction hearings to argue they had been wrongly convicted.

At Jimerson’s June 2016 hearing, Jimerson’s trial lawyer testified that he had never been told about the inmate’s recording of Vaughn. The recording cannot be located and is believed lost or destroyed.

Under U.S. Supreme Court rulings, the prosecution is required to turn over any evidence that may be exculpatory. The trial lawyers for Jimerson and Brown contended that the statement Vaughn made to the inmate might have helped cast doubt on his confession to police.

Also at a post-conviction hearing, Vaughn took the stand, and again insisted that he had nothing to do with the murder.

He also said that, despite his life sentence, he should not still be in prison. “I overdid my time,” he repeated multiple times.

When Jimerson’s attorney, Karen Daniel, of the Northwestern University School Pritzker School of Law Center on Wrongful Convictions, asked if he had understood he was pleading guilty to a life sentence, Vaughn responded, “I did, but I really didn’t know.”

After Vaughn’s testimony, Stuart Chanen, a lawyer at the Valorem Law Group in Chicago who does pro bono work, took on his case. Chanen and his team began investigating, including trying to find out if Vaughn’s mental health assessment had ever been completed. They found no record of it.

Brown had his hearing in September 2017. Nearly a year later, in August 2018, U.S. District Judge Billy Roy Wilson overturned his conviction, finding that Early’s confession, the withheld evidence, and doubts about Vaughn’s original testimony left strong doubts about Brown’s guilt.

“The only direct evidence against him,” Wilson wrote, ”was the enticed, recanted confession of a mentally deficient co-defendant that was the result of a glaring Brady violation.”

A month later, U.S. District Judge Brian S. Miller overturned Jimerson’s conviction. He expressed doubt about relying on the word of a witness — Vaughn — who “could not read and had been enrolled in special education classes until he quit halfway through high school.”

Both Brown and Jimerson are free while the state appeals. Vaughn has not been so lucky.

Vaughn, years earlier, had filed a habeas corpus petition without the help of an attorney. To file a second petition now, Chanen’s team needed permission from the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. It filed for permission in March 2017.

To Chanen’s shock, an appellate panel summarily denied the motion in January 2018.

Chanen is preparing a new motion asking the Eighth Circuit to reconsider, based on the rulings in favor of Brown and Jimerson. Such motions are rarely granted, but Chanen says it is the right outcome: Vaughn “was the one who was taken advantage of every step along the way.”

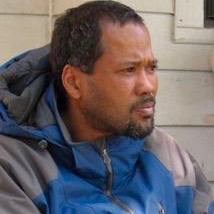

Vaughn, meanwhile, remains in the state’s maximum security unit in Tucker, Arkansas. This month he greeted Chanen, with a reporter present for the visit, by saying he was “ready to go home.” He had no clear understanding of his legal predicament.

It was his turn to be released, Vaughn continued to insist, following Brown and Jimerson.

Asked why he pleaded guilty, he responded, “They had got me confused all up. They had scared me up a bit.” He later added, “I didn’t know what was going on.”