BALTIMORE—In the cinder-block group cells at the Baltimore Central Booking and Intake Center, you might find a defendant accused of murder sitting beside a man who had one beer too many at an Orioles game. The two concrete benches on opposite sides of these tight quarters offer limited seating. It’s not uncommon to spend a night on the floor.

Joshua Insley, a defense attorney and former public defender, describes a night in jail as “hell on earth.”

But more defendants are being held without bail, according to data from the Maryland Judiciary, because the number of defendants held without bail has increased — despite bail reform that intended to let more people remain free before trial.

In February 2017, Maryland adopted new laws meant to decrease the number of people held with unreasonably high bail. It is an issue that largely disadvantaged low-income residents, said Douglas Colbert, a law professor at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law.

Bail reform has decreased the number of defendants held because they do not have the money to post the bail set for them, the court data show. But judges are ordering more people held without the chance to post bail, according to the courts — leaving almost the same number of people sitting in jail.

According to the judiciary report “Impact of Changes to Pretrial Release Rules,” bail reform was designed to “promote the release of defendants on their own recognizance or, when necessary, unsecured bond.”

The bail reform changes also say that judges can impose additional measures to ensure defendants show up for trial and to protect the community, but the judiciary is encouraged not to impose financial burden.

At the start of this year, news articles quoted sources who criticized judges, who, with the passage of bail reform, were holding more people without bail than they had been before the new rule. However, numbers later in the year have not changed much, according to the court system’s data.

Baltimore data show just 2 percent fewer people were held at their initial appearance in court in July 2018 than were were being held in January 2017, one month before the state adopted reform — from 51.5 percent at the start of 2017 to 49.5 percent last July.

Since the start of bail reform, the number of people held with cash bail in Baltimore has dropped from 35.6 percent to 14.4 percent, data show. However, the percentage of people held without bail has jumped from 14.8 percent to 34.2 percent.

Statewide data shows similar patterns. In Maryland, the number of people held with bail decreased from 29.8 percent to 18.4 percent over the past 18 months, while the number of people held without bail has increased from 13.6 percent to 22.6 percent.

Terri Charles, a spokeswoman for the Maryland Judiciary, said that “the courts and public safety [officials] have been working diligently and collaboratively to implement” the reforms in bail and pretrial release.

But some observers, including Joshua Insley, say Baltimore has been unsuccessful in its approach to bail reform because the city went in with a negative mindset.

“These are statewide rules, but for whatever reason, Baltimore City has adopted this philosophy of presumptive detention,” Insley said.

He believes judges are more likely to hold people accused of crime with no bail unless they can be convinced of an adequate reason to release defendants.

William H. “Billy” Murphy Jr., an attorney and former Baltimore judge, said that judges in Baltimore often resort to setting a high bail. He said this has not changed much since the Justice Reinvestment Act of 2016, which aimed to improve public safety, reduce corrections spending and reinvest savings in evidence-based strategies to decrease crime and reduce recidivism, according to the Governor’s Office of Crime Control & Prevention.

“Judges get caught up in the pressure of public opinion,” Murphy said. “They are attacked when someone who is out on bail commits a crime, so they set much higher bails.”

Murphy represented the family of Freddie Gray, who died after being injured in police custody in April 2015. Six Baltimore police officers were charged in Gray’s arrest and death, but all officers were either acquitted or had their cases dropped.

“The bails for those police officers were ridiculously high,” Murphy said. “The officers did not represent a danger to the public and a risk of flight.”

If a defendant is considered a risk, some jurisdictions just opt to hold them without bail, instead of turning to alternatives like pretrial services, said Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh. If assigned pretrial services, a defendant may get counseling while awaiting trial or receive a text reminding them when and where to attend their trial.

“If someone is a threat or won’t show up to court, they won’t set high bail, they’ll just lock them up,” Frosh said. “Courts will say, ‘You failed to show up three times. We’re not letting you go this time.’ ”

Charles, the Maryland Judiciary spokeswoman, said that judges look to the pretrial release rule, effective July 2017, when deciding bail. The rule was designed to promote the release of defendants on their own recognizance and suggests when additional conditions should be imposed.

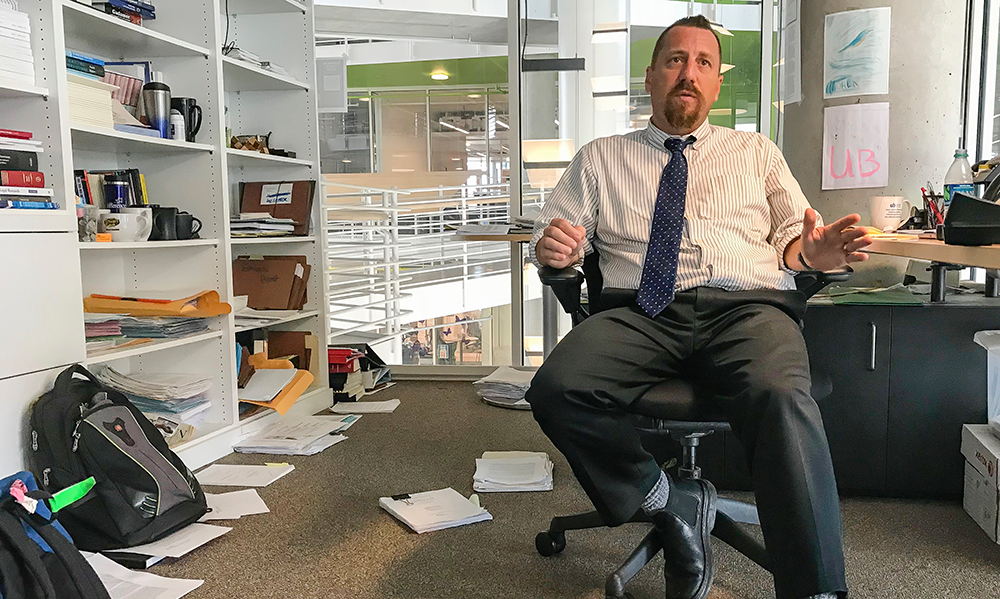

While bail reform is working in some aspects, more work needs to be done, said Colin Starger, associate professor of law at the University of Baltimore School of Law and the co-director of the law school’s Pretrial Justice Clinic. The ultimate goal of bail reform should be having fewer people locked up.

Locking up large populations isn’t going to solve issues of violence in Baltimore, Starger said.

“It’s a hard time figuring out which people are genuine threats and which aren’t,” Starger said. There’s a better-safe-than-sorry approach being used.”