- SOLOMON SIMMONS

- SOLOMON SIMMONS

(Photo by Amina Lampkin | University of Maryland)

Source: Forward Looking Infrared (FLIR) thermal imaging camera reading from 500 block of North Milton Street on August 1, 2019 at 11:20 a.m.

In July, Anchorage, Alaska, recorded 90 degrees for the first time. Europe suffered through record temperatures, with Paris hitting 109. The heat moved across Scandinavia and into Greenland, where scientists said it speeded the melting of Arctic ice that would increase flooding in coastal cities — including Baltimore.

Average annual temperatures in Baltimore have gone up more than 3 degrees over the last century, nearly twice as much as the rest of the country.

And the planet’s warming has gained momentum, say researchers who estimate the number of very hot days in Baltimore could increase six-fold by the middle of the century.

Left: The heat index on the first floor of Tammy Jackson’s McElderry Park home registered 93 degrees, 9 degrees hotter than it was outside, at 10 p.m. Sunday, July 21. Jackson has several grandchildren with asthma. (Photo by Maris Medina | University of Maryland) Right: Del. Robbyn Lewis points to trees she helped plant on North Potomac Street. (Photo by Amina Lampkin | University of Maryland)

More and more people, including Del. Robbyn Lewis, who represents parts of East Baltimore, are replacing the words “climate change” with stronger language.

“We are,” she said, “in an emergency.”

Urban heat islands

Cities, crowded and paved over, already feel the impact of climate change, with poorer air quality and streets, highways and bridges damaged by storms. But certain neighborhoods will continue to feel the effects of extreme temperatures more than others.

Researchers at Portland State University in Oregon and the Science Museum of Virginia have mapped these areas, called urban heat islands, and data shows that temperatures here and in surrounding neighborhoods can run 8 degrees hotter than in communities that have more trees and less pavement.

McElderry Park, which despite its lyrical name offers little green space, is one of these: the hottest neighborhood in Baltimore, a city whose climate has long been classified as humid subtropical.

Residents in the hottest areas have higher rates of chronic illnesses affected by heat, including asthma and COPD. In hot weather, emergency medical calls for some chronic conditions increase. The rate of emergency medical calls for cardiac arrest and congestive heart failure, for example, nearly double when the heat index hits 103 degrees.

"When we talk about the environment,” Lewis said, “we’re talking about human health.”

The city’s hottest areas are poorer, which means the residents don’t have the resources to move out.

This is true across the United States. In a majority of the country's most populous cities, people with lower incomes typically lived in the hottest areas, an investigation by journalists from NPR and the University of Maryland found.

In short, as the planet warms, the urban poor in dozens of large U.S. cities will actually experience more heat than the wealthy, simply by virtue of where they live.

Sacoby Wilson, who studies applied environmental health as an associate professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Health, said people in low-income neighborhoods walk more, ride more buses and drive fewer cars — so they contribute less to climate change. And yet they are more vulnerable to dying in extreme heat.

“Environmental justice and climate change,” Wilson said, “are inextricably linked.”

The streets have fewer trees than those in more affluent communities. Rowhouses, Baltimore’s signature architecture, trap heat and stay hot even when the heat eases on summer nights. The houses are old, often poorly insulated and hard to maintain. Crime rates are higher, so many people won’t put an air-conditioning unit in a first-floor window for fear of break-ins.

The problems are not new. Many stem from historical segregationist zoning and lending policies that for decades limited where black citizens could live.

“We have to root ourselves in the reality that Baltimore for all this great history has a history of inequality and racism that we don’t like to talk about,” Baltimore City Council President Brandon M. Scott said.

The Code Red weekend

As July’s weather emergency bore down, Baltimore’s health department put out press releases advising citizens to drink water and cut back on outdoor activities. At a Thursday press conference warning of a 100-degree weekend, the mayor told Baltimoreans to stay inside until the weather broke Monday night.

Radio and television stations dutifully broadcast that the city opened cooling centers, where people could rest during the most intense heat. City health officials said the information was also available on its website.

But many East Baltimoreans said during the heat wave that they weren’t aware of any of City Hall’s plans or warnings. Many said they didn’t know cooling centers existed. They never looked at the website.

Inside the rowhouses, even those with an air-conditioning window unit, the heat simmered.

Reporters from the University of Maryland’s Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service placed sensors that record heat and humidity inside several homes in McElderry Park and nearby neighborhoods. Those sensors recorded temperatures that reached as high as 97 degrees and heat index values of 119 degrees.

In some homes, those readings showed that it was hotter inside than outside.

Sensors record startling heat

At 4 p.m. Saturday, July 20, the temperature in Baltimore hit 99 degrees, but the humidity made it feel like 108 degrees. Here is what the combination of heat and humidity felt like inside three East Baltimore rowhouses at 4 p.m. that day:

On the first floor of Tammy Jackson’s two-story rowhouse, the heat index registered 93 degrees at 10 p.m. on Sunday, July 21. Outside, the heat index was 9 degrees lower, 84 degrees.

Stephanie Pingley said she won’t let her three sons — 13, 11 and 7 — play outside the home she rents in the 500 block of her street. “Drugs in the 400 block,” she said. “Drugs and alcohol in the 600 block.”

A sensor inside a bedroom showed that the heat index during the heat wave was consistently higher inside than outside Pingley’s house.

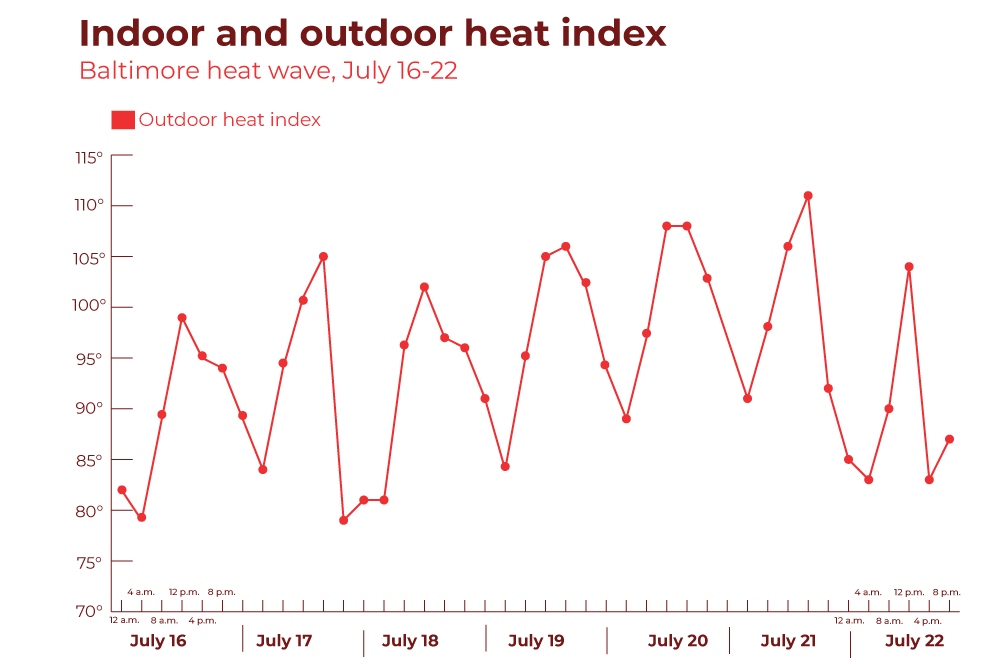

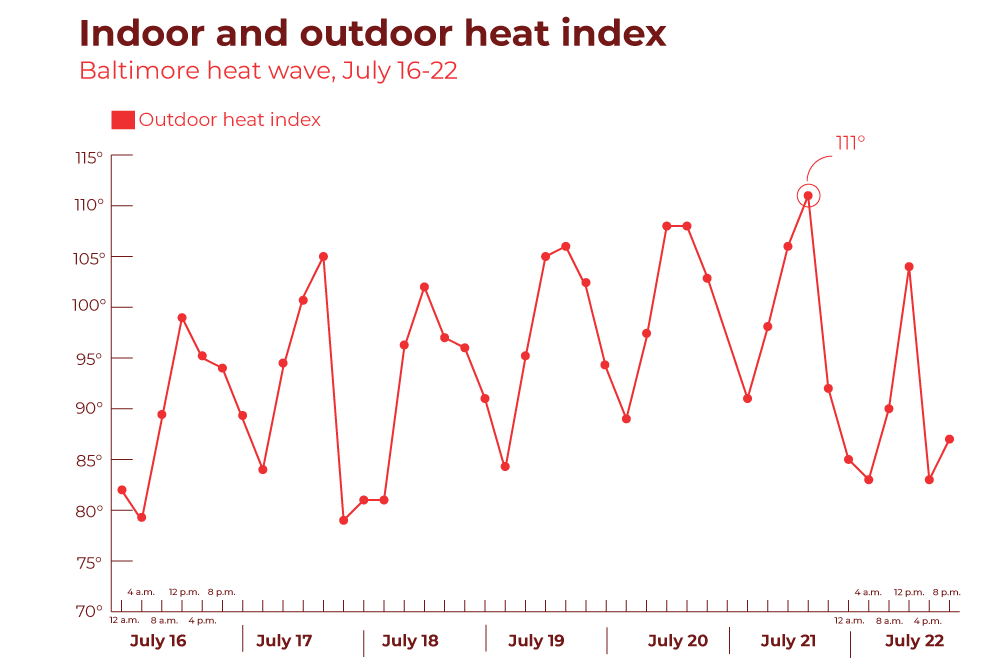

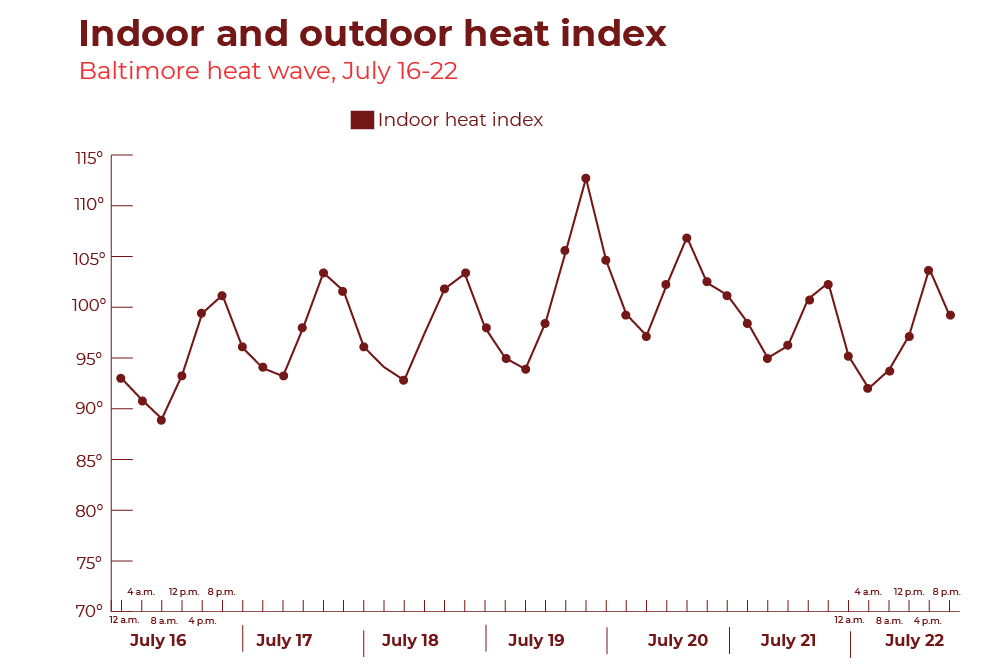

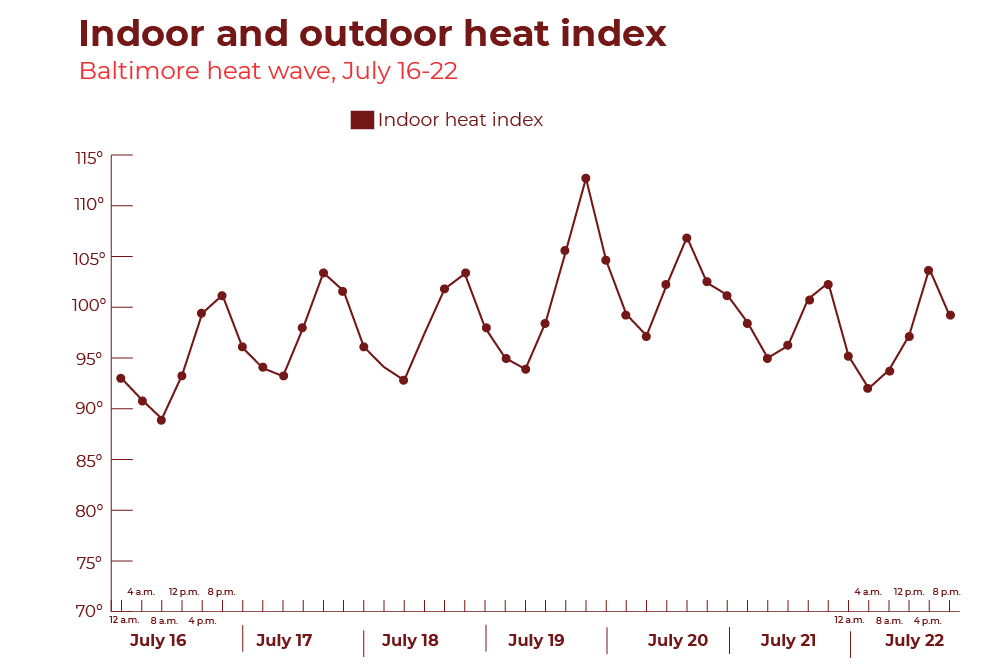

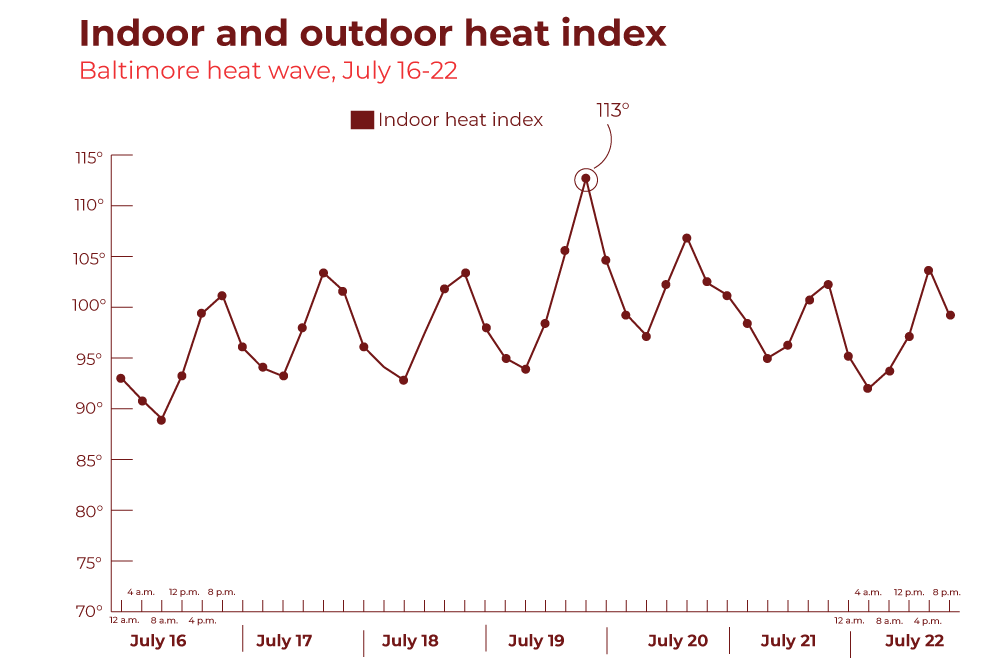

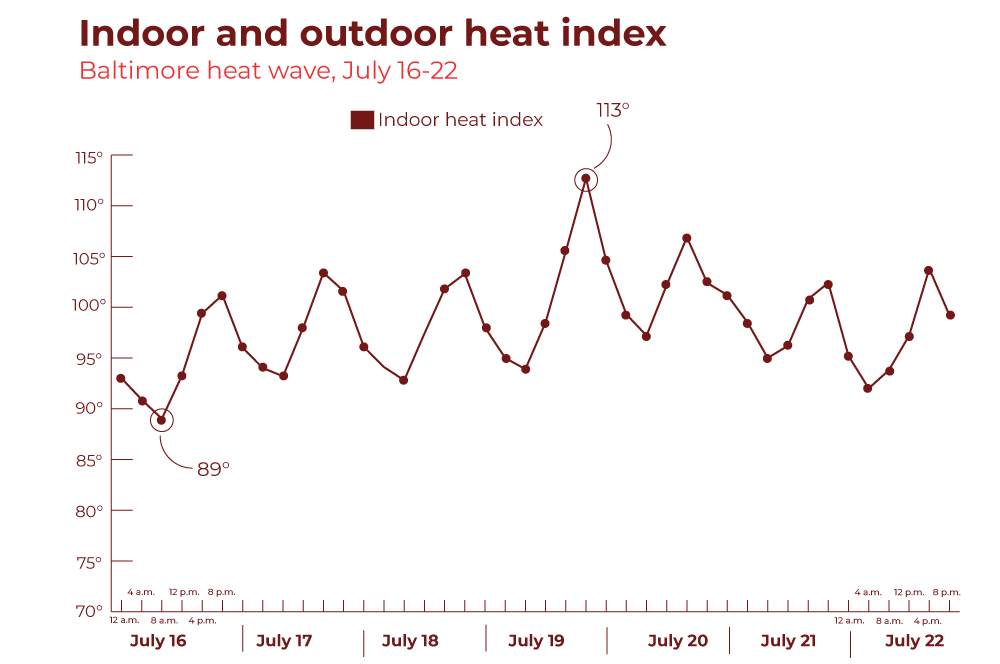

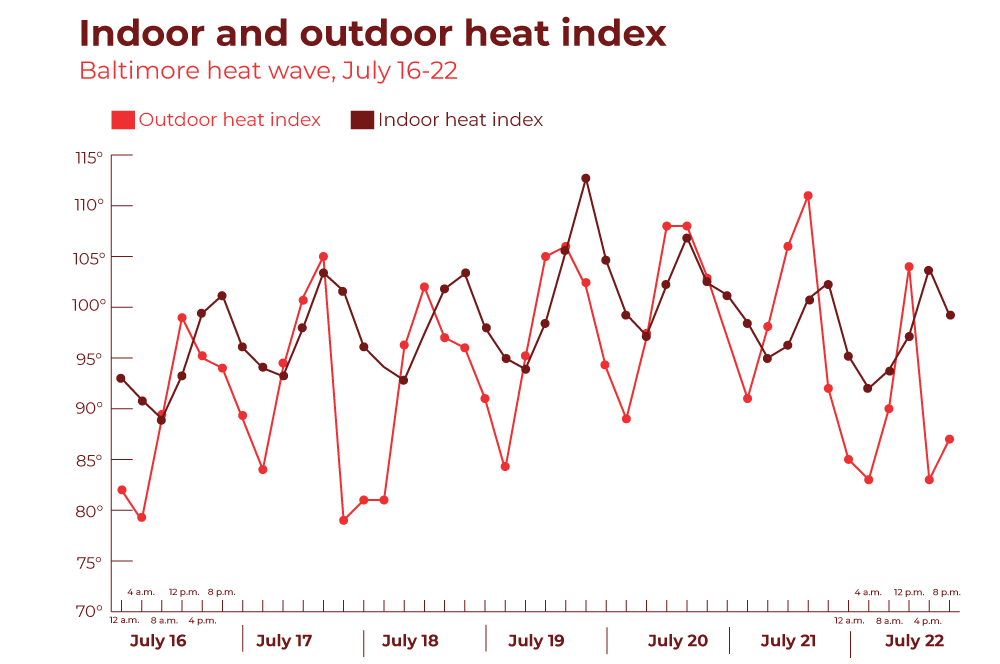

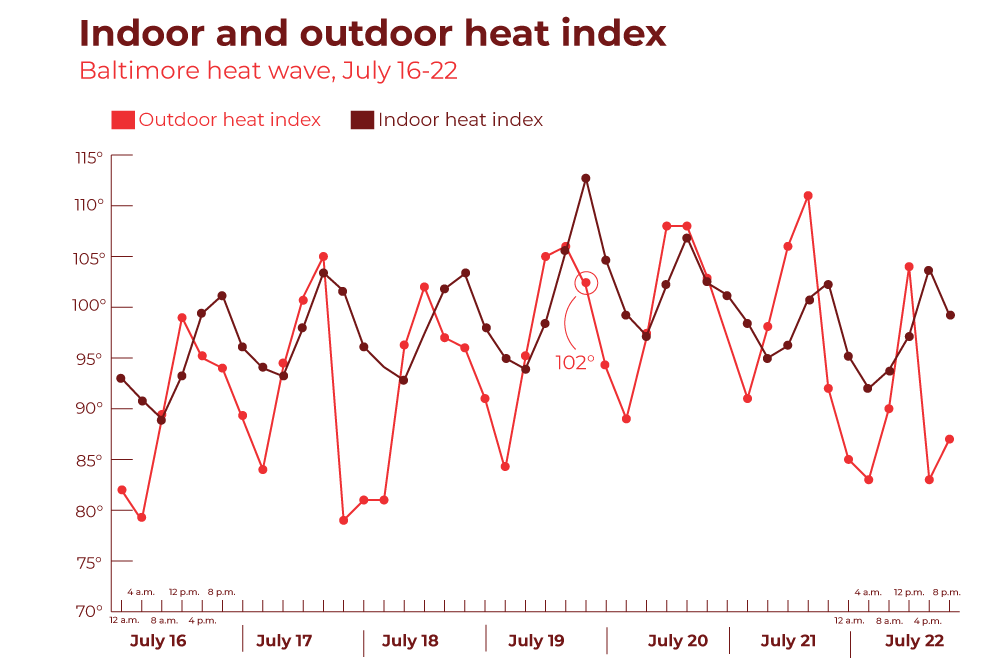

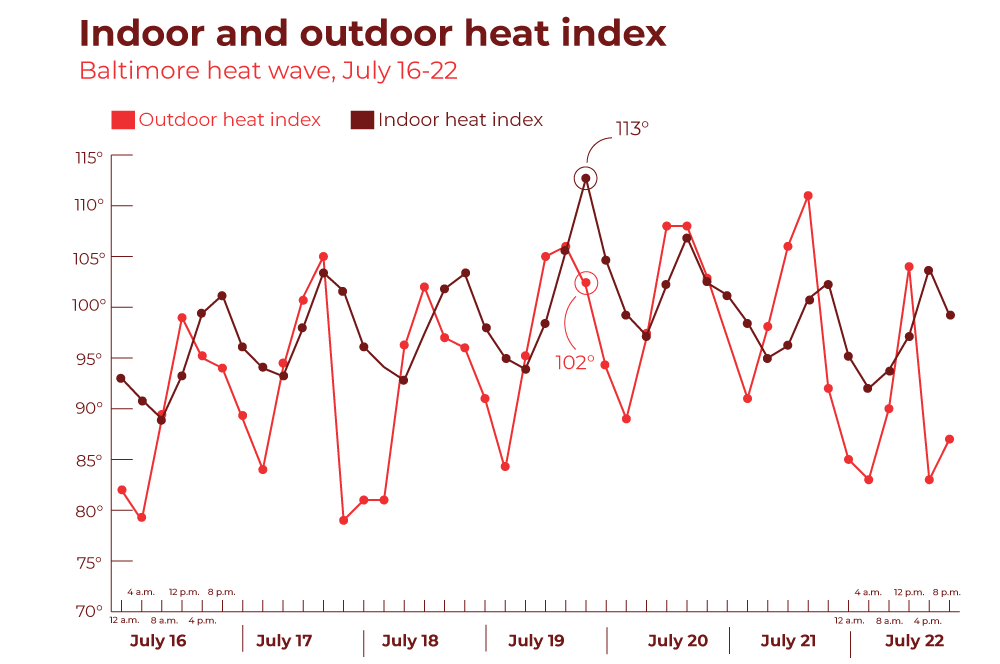

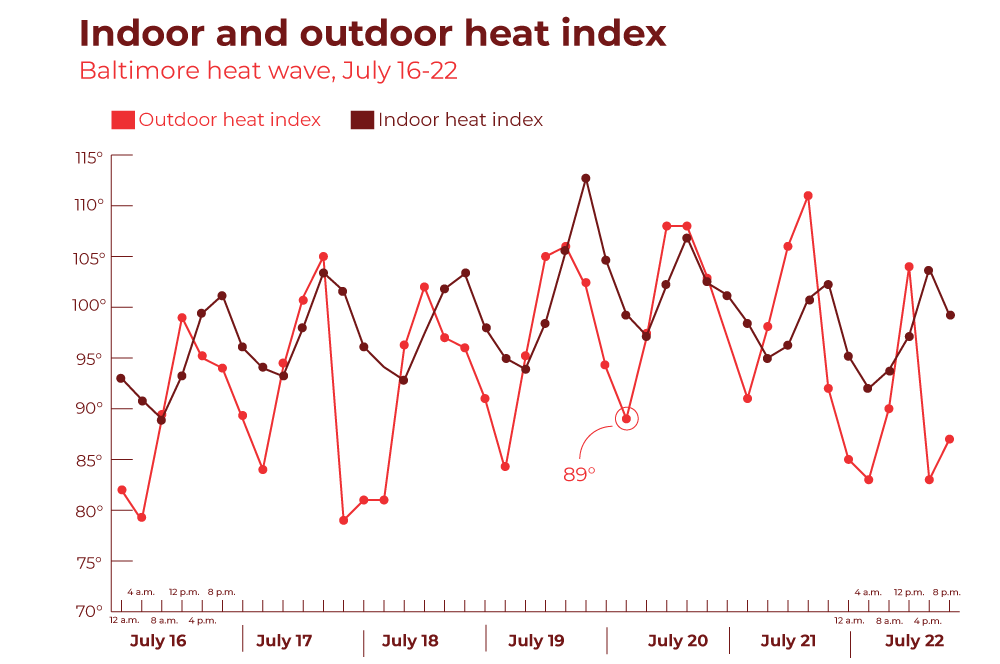

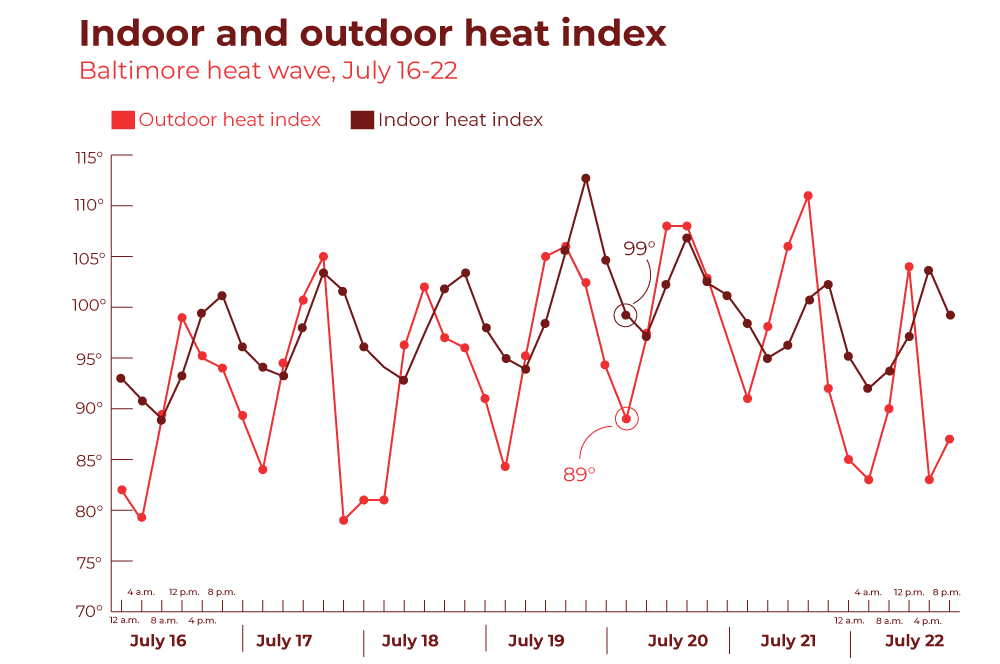

A heat wave hit Baltimore in July 2019.

The seven-day stretch between July 16 and July 22 were the hottest consecutive days of the summer.

The heat index reached 111 degrees at 4 p.m. July 21.

University of Maryland journalists used sensors to continuously record indoor temperature and humidity readings inside Stephanie Pingley’s home.

The sensor was placed in an unairconditioned second-floor bedroom where two children sleep.

The heat index reached 113 degrees at 8 p.m. on July 19; it averaged 98 degrees during the seven-day period.

The average hourly heat index in the bedroom never dropped below 89 degrees.

The heat index was consistently higher inside Pingley’s home than it was outside.

At 8 p.m. July 19, in the midst of the summer's most brutal heat wave, the outdoor heat index hit 102 degrees.

Inside Pingley’s house, it was 11 degrees hotter, with a heat index of 113 degrees.

At 4 a.m. July 20, the heat index in Baltimore was still 89 degrees.

Inside Pingley’s house, in the bedroom where two children sleep, it felt even hotter, with a heat index of 99 degrees.

Source: Federal government weather data via Iowa State University and indoor temperature and humidity sensor data captured by University of Maryland journalists. Graphics by Adam Marton. Data analysis by Theresa Diffendal, Krishnan Vasudevan and Sean Mussenden.Still, she said an air conditioner in the kitchen provides enough relief for the family during the day. She would rather stay home with the shades drawn against the heat than walk her children a mile to a cooling center.

In the neighborhoods

Here’s how the July heat wave felt to the residents of some East Baltimore neighborhoods:

On that Friday, as the worst of the heat wave was taking hold, Myron Watson, a construction worker, was walking to pick up his daughters from summer camp. He said he’s careful to drink water while he’s working outside. But in that week’s above-90-degree heat, “I felt sick a couple of times, kind of nauseous.”

As the summer had gotten hotter, Watson had been taking fewer buses, waiting at fewer hot bus stops. Instead, he was calling ride shares and traveling in air conditioning. He’d heard nothing about the city’s cooling centers.

By Saturday, the heat index inside the second-floor apartment of Michael Thomas and Alberta Wilkerson hit 112 degrees. A fan pushed hot air around. Thomas, 61, has emphysema. Wilkerson, 49, has had a heart attack.

“Just living through it,” Thomas said.

On Sunday, Solomon Simmons, who is retired from a job at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, went to Hope Community Church, where he is a deacon. “We had trouble getting the church cool,” he said. And far fewer people attended services.

(Photo by Amina Lampkin | University of Maryland)

Security concerns

Simmons, 70, and his neighbor Harriett Alexander said McElderry Park used to be more tightknit — “like a village,” Simmons said.

Public health studies have shown that without community cohesion, residents are at more risk when temperatures soar. Baltimore health officials say that isolation is always a danger to health.

Today, Simmons said, many of his old neighbors have died. Only about four people remain from the group of homeowners his mother met when she moved to McElderry Park in the 1980s.

Some residents of McElderry Park say they will not install window air conditioners on the first floor of their rowhouses for fear they offer easy entry for burglars. (Photo by Otto Blais-Nelson | Wide Angle Youth Media)

“Pride is gone,” he said.

He will not put an air-conditioning unit in a first-floor window facing the street “because of security.” He has air conditioning in his bedroom, but he’s mindful that using it costs money.

“One of the things that does concern me is that my electric bill will probably be a lot more just trying to stay cool.”

He said he didn’t know about cooling centers but would rather take an air-conditioned drive or go to the movies than sit in a cooling center.

Alexander, retired from Armco Steel and the Baltimore school system, follows the old Baltimore practice of scrubbing her rowhouse’s white marble steps often. She used to scrub the steps of neighbors’ houses as well. “It’s important to me,” she said. “This is where I live.”

She tends large pots of hostas and lilies that bloom next to her rowhouse steps, and on summer days she sits in the shade of a mature sidewalk tree and chats with neighbors. She has air conditioning in her second-floor bedroom but doesn’t like using it because she fears she wouldn’t hear if anyone was breaking into her house.

“I don’t think it safe to live in a house with an air conditioner running, drowning out everything else,” Alexander said. “You don’t know someone’s in your house until they’re in your room.”

But especially for children, older residents and people coping with chronic diseases, air conditioning is the answer.

Tammy Jackson, who has asthma, said she had to stop cooking dinner one July evening when the heat made it hard for her to breathe. The next day, she told her husband, “Baby, I can’t cook until I get AC.”

Even if someone from McElderry Park decided to find a cooling center, some centers were closed on the weekend. The closest center open Saturday and Sunday was about a mile away — a long walk for the young or the old in 100-degree heat.

Jennifer Martin, Baltimore's deputy health commissioner for population health and disease prevention, said she was “sad and surprised” to hear so many people were unaware of the cooling centers.

By the end of July, the health department had declared 12 Code Red days this year, and the department counted 2,454 people who had visited cooling centers.

Martin said the health department is working with community groups to find places in addition to city-owned buildings — maybe churches or community associations — where residents could find a place with air conditioning. Those would offer relief closer to home.

Scott, the City Council president, said that cooling centers are fine but may not be the answer for everyone. “We have to understand the culture of the neighborhood. Some people are not going to want to be leaving their homes to get cool,” he said.

Lewis said, “We wouldn’t need cooling centers if we had healthy neighborhoods.”

Heading off catastrophe

Twenty people have died of heat-related illnesses in Maryland so far this year, three of them in Baltimore, according to state data through Aug. 28.

From July 16 through July 22, when the heat wave broke, 47 people went to emergency rooms when the heat aggravated chronic conditions such as heart disease, diabetes or lung problems.

Yet it could have been worse. Heat catastrophes are not theoretical. In Chicago in 1995, more than 700 people died during a five-day heat wave.

And summer heat will get more extreme. With every year, researchers warn, temperatures will soar higher and the heat waves will last longer — putting more pressure on city governments to help residents cope.

Historically, the Baltimore area has averaged about six days a year when the heat index exceeded 100 degrees, according to new research from the Union of Concerned Scientists and the University of Idaho.

State of the Climate 2018

The American Meteorological Society releases a State of the Climate report each summer summarizing data collected by global environmental monitoring stations around the world. In 2018, here were five key findings.

Source: American Meteorological Society's The State of the Climate in 2018

If no action is taken to reduce carbon emissions, by mid-century that figure will rise to more than 37 days annually, according to the researchers. The study defines mid-century as starting in 17 years.

By the end of the century, as a baby born today becomes a senior citizen, there will be 65 days with a heat index of 100 degrees or higher, the researchers projected. That’s about the same number as McAllen, Texas, a city that abuts the Mexican border.

Peter Beilenson, Baltimore’s health commissioner from 1992 to 2005, now the health services director of Sacramento County, California, said health departments could use different strategies to deal with extreme heat.

Public health workers could be redirected during heat waves to knock on doors of people who are most vulnerable to heat, he said. That would allow workers to hand out information on cooling centers and give them a chance to assess whether the resident needs to go to the emergency room.

The Baltimore health department has done this to deal with other problems, Beilenson said — for example, to check on tuberculosis patients or alert residents to the dangers of lead paint.

This block at the edge of the city's McElderry Park neighborhood had tree canopy coverage of about 8% in 2015. (Photo by Katia Crawford | Wide Angle Youth Media)

Candidates for office have long used data that tells them which doors to knock on to meet potential voters. Health workers, Beilenson said, could use data to find the most vulnerable during heat waves.

Martin said the health commissioner had recorded a call warning of the heat that was sent to older people who have used the city's services for aging. But during the 100-degree Code Red emergency, Martin said, the health department did not send teams into neighborhoods.

“Being able to identify vulnerable areas [where people are especially endangered by heat] is very challenging,” she said. Also, “in a heat wave, everyone is at risk, including people who knock on doors.”

Trees help with heat

When Baltimore officials are asked how the city is preparing for the more extreme temperatures ahead, several people point to the efforts by City Hall and volunteer groups to plant more trees. Citywide, the tree canopy in 2015 was 28%, up from 27% in 2007.

In 2015, many East Baltimore neighborhoods had a tree canopy of about 10%, according to a Howard Center analysis of tree canopy data gathered by researchers at the U.S. Forest Service and the University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab. Many blocks had no trees at all.

Some city officials resist questions about where climate change falls on the list of government priorities when City Hall has to deal with poverty, crime, police corruption, poor schools and crumbling infrastructure.

“I don’t like to rank things,” said Scott, the City Council president. “For me, when you’re thinking about issues like heat, that’s connected to safety. It’s all interconnected. We need to stop thinking in silos.”

He acknowledges that “trees and climate change were not a high priority for mayors and council members of Baltimore’s past.”

The question, said Scott, who is expected to be a mayoral candidate next year, is “how can we evolve and get more innovative about this discussion?”

At the end of July, Scott released an agenda with 26 priorities for the coming council year. Climate change was not among them.

Rowhouses in the heat

Rowhouses efficiently conserve heat — which is welcome in the winter, a problem in the summer.

On a hot summer day, Melissa Canady walked through the alley behind her rowhouse. The backyard is concrete, poured by a previous owner to create a space that could be cleaned by a broom. Concrete blocks form low walls that separate each yard.

“The neighborhood’s so closed in,” she said. “There are so many houses. There’s no air flow. If there was some way you could get some air into the community.”

Her backyard looks out onto a patch of green, the Amazing Port Street commons, a block of green space cared for by Amazing Grace Lutheran Church and created when a row of vacant houses was razed. The neighbors sometimes use it for events such as community cookouts.

It’s the largest green space for blocks. But some neighbors said they are reluctant to walk their dogs there for fear they will step on syringes discarded by people who use drugs.

Top: The garden entrance at Amazing Grace Evangelical Lutheran Church is one of the few green spaces in the McElderry Park neighborhood. (Photo by Ian Round | University of Maryland) Left: Melissa Canady says that the concrete block walls in her backyard prevent the flow of air and trap heat behind her house. (Photo by Maris Medina | University of Maryland) Right: Harriett Alexander, with her dog, Shakur, doesn’t like using her air conditioner because she might not hear someone breaking into her house.

Coping with the heat

As temperatures in Baltimore reached 100 on July 20, most everyone around the city was staying inside. Some of the people on the streets walked under open umbrellas, carrying their own circle of shade. Men wore damp cloths draped under their caps or on the backs of their necks. No one was moving quickly.

Few people were on the street. “This is the quietest the block ever been,” Tammy Jackson said. “I can’t believe it.”

But city life continued despite the heat. A team of paramedics was called to an East Baltimore block when a resident found a man she didn’t know passed out on her front steps.

The paramedics revived the man, who apparently had overdosed, with a dose of Narcan. He stood up and wandered off, rejecting advice he go to the hospital.

One of the paramedics, holding a bottle of water, stood on the sidewalk and surveyed the quiet street. Everyone walking around on that scorching afternoon was dehydrated, one paramedic observed. Everyone. Keeping enough fluids in the body is difficult in temperatures so extreme.

A little earlier that day, David Brown, 68, sat a few blocks away waiting for a bus. He said he didn’t mind the heat.

And what will he do in future summers, as the heat becomes more extreme?

“Accept it,” he said.

Jake Gluck, Jane Gerard, Xander Ready, Theresa Diffendal and Sean Mussenden of the University of Maryland contributed to this story. Additional information was also provided by Sean McMinn, Meg Anderson and Nora Eckert of NPR.

ABOUT THIS PROJECT: This work is a collaboration between the University of Maryland's Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service, NPR, Wide Angle Youth Media in Baltimore and WMAR television. Learn more about the reporting behind the stories here. Read the first installment of this investigation into the effects of climate change on public health in Baltimore, "Bitter Cold."

FUNDING FOR THE PROJECT: Support for this project comes from generous grants from the Scripps Howard Foundation, the Park Foundation, the Online News Association, the Annie E. Casey Foundation and the Philip Merrill College of Journalism.