April 22, 2016

Homeowners Forced to Relocate Due to Purple Line Plans

Next door to Wise Lampkin's home on Riverdale Road in Maryland sits an empty home. The neighbor who lived here settled with the state in early January 2015 to make way for the Purple Line, according to documents provided by the Maryland Transit Administration. (Capital News Service photo by Brittany Britto)

RIVERDALE -- Wise Van Lampkin’s home sits on Riverdale Road, tucked between the memories of two neighbors. To the east, there is only a vacant lot, sprinkled with straw. To the west, the house is stripped of its siding, windows shattered.

Lampkin’s, a welcoming yellow house with wooden shutters, will be vacant soon.

His home, which he bought in April 1995, belongs to the Maryland State Highway Administration, to make way for the state’s newest transit project, the Purple Line.

The Purple Line will be a 16.2-mile double track light rail with 21 stops running from Bethesda in Montgomery County to New Carrollton in Prince George’s County.

The $5.6 billion transit project will connect to the red, green and orange Metro lines, as well as all three MARC Train lines and Amtrak, and is projected to create more than 23,000 jobs within the state over six years, according to Gov. Larry Hogan’s administration. The state transit administration plans for trains to begin running in the spring of 2022.

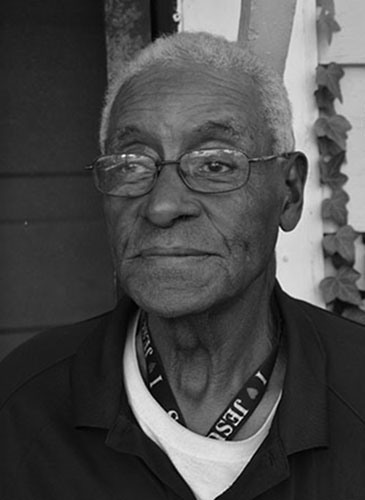

Wise Lampkin, 84, of Riverdale, Maryland, received a notice in the mail from the Maryland Transit Administration more than a year ago. The letter told him that his property would be taken by the state to make way for a public transit project, the Purple Line. By April, he was still living in the home, but a house next door had been torn down. (Capital News Service photo by Brittany Britto)

But in the process, more than 150 homes will be impacted.

According to the Maryland Transit Administration’s August 2013 Purple Line impact statement, a total of 25 single-family homes in Maryland are being fully acquired by the State Highway Administration to make way for the light rail line, meaning residents in the area will have to relocate and look for new places to live.

More than 120 residential properties, including apartment units, will undergo partial acquisitions, meaning portions of the properties, such as front yards, can be taken -- permanently or temporarily -- for construction purposes.

Riverdale will be one of the hardest hit.

Twenty-two homes in the Riverdale area will be fully acquired before preliminary construction is set to begin later this year to make way for the line, which will lead to a new station -- Riverdale Park. More than half are already sold and vacant, and some have already been demolished, making way for major construction that will most likely begin later this year, according to the Maryland Department of Transportation.

At least 20 owners in Riverdale have already settled with the state -- including Wise Lampkin. West of Lampkin’s home, the owner settled in January 2015 for around $155,000, according to state property tax records. To the east, the owner of the neighboring home settled in August 2014 for $149,000.

In mid-October, Wise Lampkin signed over his property for $131,000. The sale was finalized in November, according to property records, but it was not without a struggle.

The 84-year-old has lived on Riverdale Road for two decades.

His home was the base for holidays and events for him and his family of 12 -- including his wife, eight daughters and two sons. It was a safe haven for his nephew and two daughters who once lived there. It was the reason he and his wife stayed together, Lampkin said.

Now, Lampkin lives alone. His wife died 2011. His 10 children, the youngest one now in her 40s, have all grown up.

The two-bedroom, one-bathroom home is modest in size, but it was something he wanted to pass on to his children.

“I want them to have something we had,” Lampkin said before the settlement was made.

The senior citizen, who works at a nearby car dealership as a lot attendant, said he has been pouring himself into the home since he bought it in 1995.

“I’ve been spending money on this house,” Wise Lampkin said, pointing to the pavement, which he installed himself years ago with a pick and shovel -- “the old-fashioned way.”

It would hurt him to move, he said, “but they’re going to do what they got to do.”

If worse comes to worst he will move in with his daughter Betty Lampkin, he said. She takes care of him.

There was no compassion at all.

- Betty Lampkin, Daughter of Homeowner Wise Van Lampkin

The 59-year-old, who lives in Washington, is the oldest of Wise Lampkin’s eight daughters and acts as his caretaker.

Late last year, she sat outside the Riverdale home in a silver car, out of earshot of her father, who she said gets visibly upset whenever anyone brings up the Purple Line and his home.

“It just tore him down mentally. He’s so discombobulated. It’s just sickening,” Betty Lampkin said of her father, who in his old age, is forgetful and displays early symptoms of dementia.

Betty Lampkin, who visits her father regularly, initially had no idea that her father’s house was in jeopardy. She hadn’t seen the many envelopes that had been arriving at the house, and her father wasn’t reading them.

“He didn’t think about half the mail -- he wasn’t looking at it. He wasn’t opening it. That should have told (the Maryland Transit Administration), ‘Okay, we’re not getting a response from this person. We need to do more research.’ They didn’t do any research. They just kept sending correspondence and not getting any answer. That should’ve raised a red flag,” Betty Lampkin said.

Had they came to see him, Betty Lampkin said, her father would have called her and she could have jumped in a long time ago. She only learned about the transit plans in summer of 2014 through her nephew who found the envelopes. Since then, the process since has been an inconvenience, she said.

Busy with a family of her own and searching for steady employment, Betty Lampkin is working to finish her associate’s degree, a feat she nearly gave up on after her mother’s death in 2011.

On top of it all, Betty Lampkin has never owned a home.

“I’m in school, and I can’t get my stuff done because I’m working on this. This is new,” Betty Lampkin said of this transition with her father and the home. “I don’t know how to do this. It’s like having a newborn baby.”

There were several papers to sign and the option to go to court to appeal and request more money in the settlement, but ultimately, Betty Lampkin said, she and her father had no choice. They were told they would have to give up the property voluntarily or involuntarily.

“There was no compassion at all,” Betty Lampkin said.

After settling in October, the family initially had until mid-January to move out, but yet to find a home, Betty Lampkin prolonged her father’s stay, hoping to keep him until the last minute possible. In December, Betty Lampkin said, she was given 30 days notice, but in January, she still wasn’t ready. She communicated with the transit administration and set a March deadline for herself. But now April is here, and Betty is still looking for a new home for her and her father.

“I don’t have any place for him to sleep, and they’re pushing me hard,” Betty Lampkin said.

More than 20 homes in Riverdale, Maryland, will be bought by the Purple Line in order to make way for the light rail. This house was sold to the state over a year ago. (Capital News Service photo by Brittany Britto)

But the Maryland Transit Administration recognizes that property acquisitions put pressure on businesses and homeowners. It is often a part of any important state project involving construction, Sandy Arnette, Maryland Transit Administration spokeswoman, said.

“Maryland Transit Administration carefully follows all federal and state laws and offers fair market values during property acquisitions. We also work closely with all property owners to ensure they are treated in a fair and equitable manner,” Arnette said.

Betty Lampkin tried to do what she could to fight for the house. She hired an attorney -- a friend of a friend -- but she said it wasn’t worth it; not only because the house would be lost to the state regardless, but because the attorney disappeared.

“I called and left her messages, and she never returned my messages,” Betty Lampkin said.

To get her father to sign the papers to relinquish the property was one of the most difficult things she ever had to do, Betty Lampkin said.

“To take him out of his environment and revamp his whole life, it has been an emotional rollercoaster ride for me, and especially for him,” Betty Lampkin said. “He just felt like he was being taken advantage of.”

“‘My wife is gone. My house is gone. Now I don’t have anything’,” he would say to her.

“That’s all he knows since my mother was living there,” Betty Lampkin said.

Mindy Fullilove, a psychiatrist and professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University’s school of public health, said that the sense of loss that a family feels when being forced to move is more than just grief and pain.

Moves like Wise Lampkin’s can shake up core psychological processes for the homeowners.

Fullilove has studied the effects of moving and urban renewal for the past 20 years and said she believes that though public transit is a legitimate public taking for the greater good, governments should be more mindful of the eminent domain process and how moving affects residents in the long term.

For people like Wise Lampkin, a house is not just a house -- it’s a way of life, Fullilove said.

“A house is located in a neighborhood and city. The people you know are connected to a house. All of those things are interconnected ... In a way, when you lose a space that you lived in with a (significant other), you lose the memories,” Fullilove said.

Many people, especially those older in age, feel especially disoriented after being relocated, said Fullilove, referring to this process as a part of orientation psychology.

“It’s a process where we know where we are in a space. We know where things are that we need, both in the house and neighborhood. It shakes you up and everything you think you know about the world,” said Fullilove.

A home closely relates to a person’s identity, and that sense of belonging and orientation for a healthy life is not optional, Fullilove said.

The Maryland Department of Transportation has spent $19.3 million on property acquisition for the Purple Line through October 2015, according to Maryland Transit Administration. An estimated total of $263.5 million has been budgeted for property acquisitions between the 2016 and 2021 fiscal years.

The Maryland Transit Administration has declined to comment on negotiations that are still in process, but a relocation assistance program document provided by the Maryland Transit Administration said that the owner of a home may be eligible to receive payments to help purchase a replacement home as well as assistance with any moving costs or increases in mortgage payments if asked to relocate.

Betty Lampkin has said that the state has offered to pay off Wise Lampkin’s home loan along with his moving costs and storage for up to two years.

And though Betty Lampkin can put some of the settlement money toward a house, she said, her father still wants his space and independence.

“He wants this house -- that’s it. He doesn’t want to move with anybody.”

But neither of them have a choice, Betty Lampkin said.

Wise Lampkin currently pays around $800 a month for his home, a deal Betty Lampkin said would be hard to find elsewhere. But now, he is living on a ghost street of vacant homes.

According to Betty Lampkin, the transit administration has expressed concerns about her father being alone on the block, since he is one of the last residents left on Riverdale Road, and his home is surrounded by vacant properties.

“They think they are doing people a favor by making sure he’s in a safe environment,” Betty Lampkin said, but really, the Maryland Transit Administration is putting her under immense amounts of stress.

The final decision for the Purple Line was made April 6 at the state Board of Public Works meeting where the $5.6 billion contract was approved.

“It’s putting pressure on my family to uproot my home and his, because I don’t have the space. They just care about putting the (Purple Line) in there,” said Betty Lampkin, noting that moving out this month is not practical. She will be putting it off as long as she can to buy time, she said.

Betty Lampkin still has to find a home. She has to choose the storage unit for her father and send the bill to the transit administration. She has to get estimates from at least two moving companies, and then she has to wait for the state, which will make the final decision. Only then can she and her father pack up the house and the memories and start anew.

“I’ll be glad when it’s over,” Betty Lampkin said.