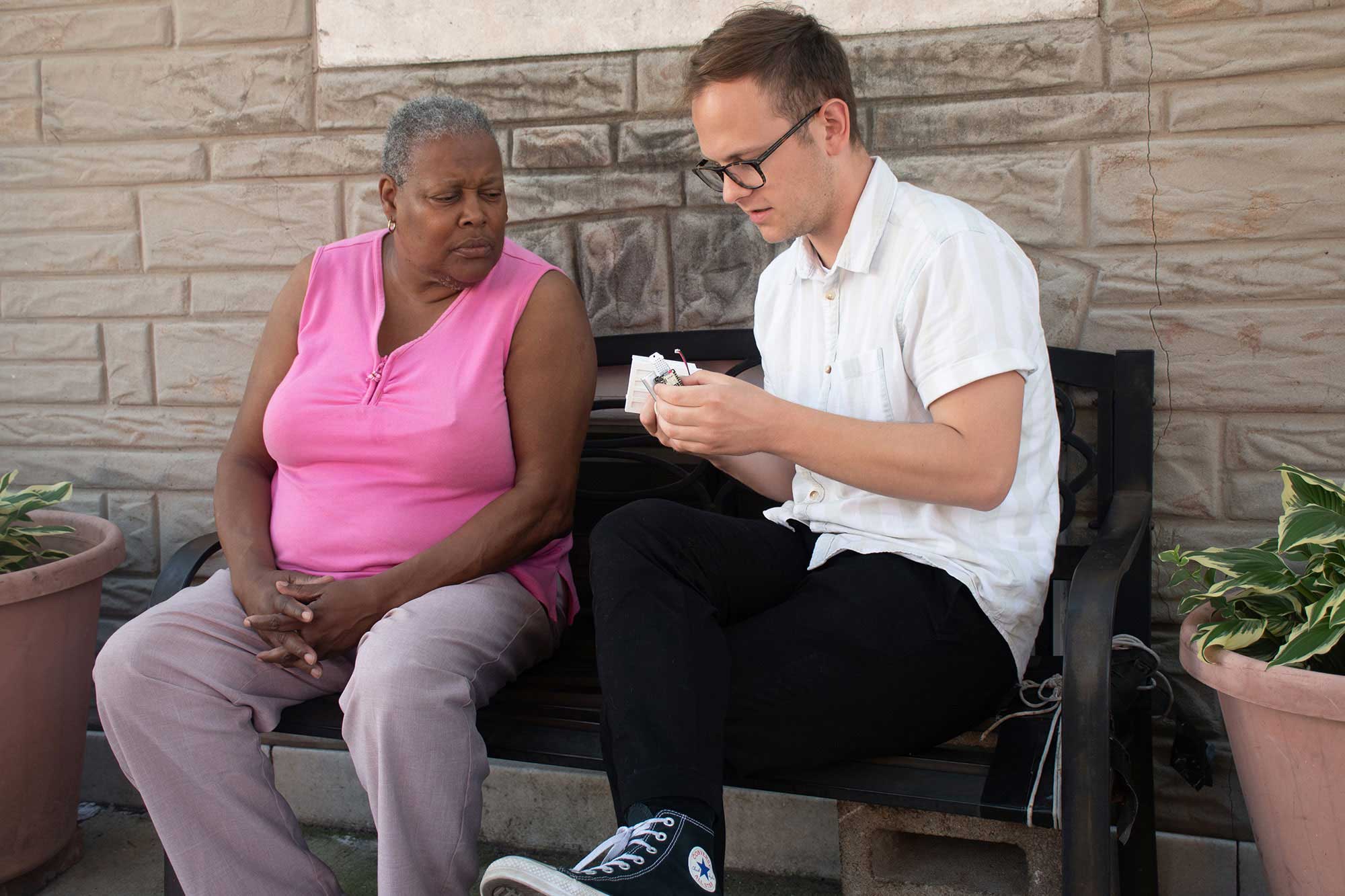

(Top photo by Amina Lampkin | University of Maryland)

A summer in Baltimore’s hottest neighborhoods

September 3, 2019

A year and a half ago, journalists at the University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism and NPR started planning an ambitious reporting project to cover one of the most important challenges of the modern era — the accelerating climate crisis.

It’s a global topic, of course, and there are thousands of journalists reporting thousands of stories, including the rapid melting of Greenland’s ice sheets, the increase in wildfires in the American West, ocean acidification killing coral reefs, oil companies hiding climate change evidence, and rising temperatures that are quickly making some parts of the world unsuitable for human habitation.

For our part, we wanted to develop a deep understanding of how climate-change driven temperature increases were already affecting the health of people in our own community, in Baltimore, Maryland. We spent a year gathering and analyzing data and talking with climate and health experts. We built temperature and humidity sensors to help understand what it was like to live in rowhouses in Baltimore’s hottest neighborhoods. Our data analysis identified McElderry Park as the city’s hottest neighborhood, and we spent a summer reporting on the community and the people who live there.

Here’s how we did it.

Monitoring heat and humidity in homes with data-collecting sensors

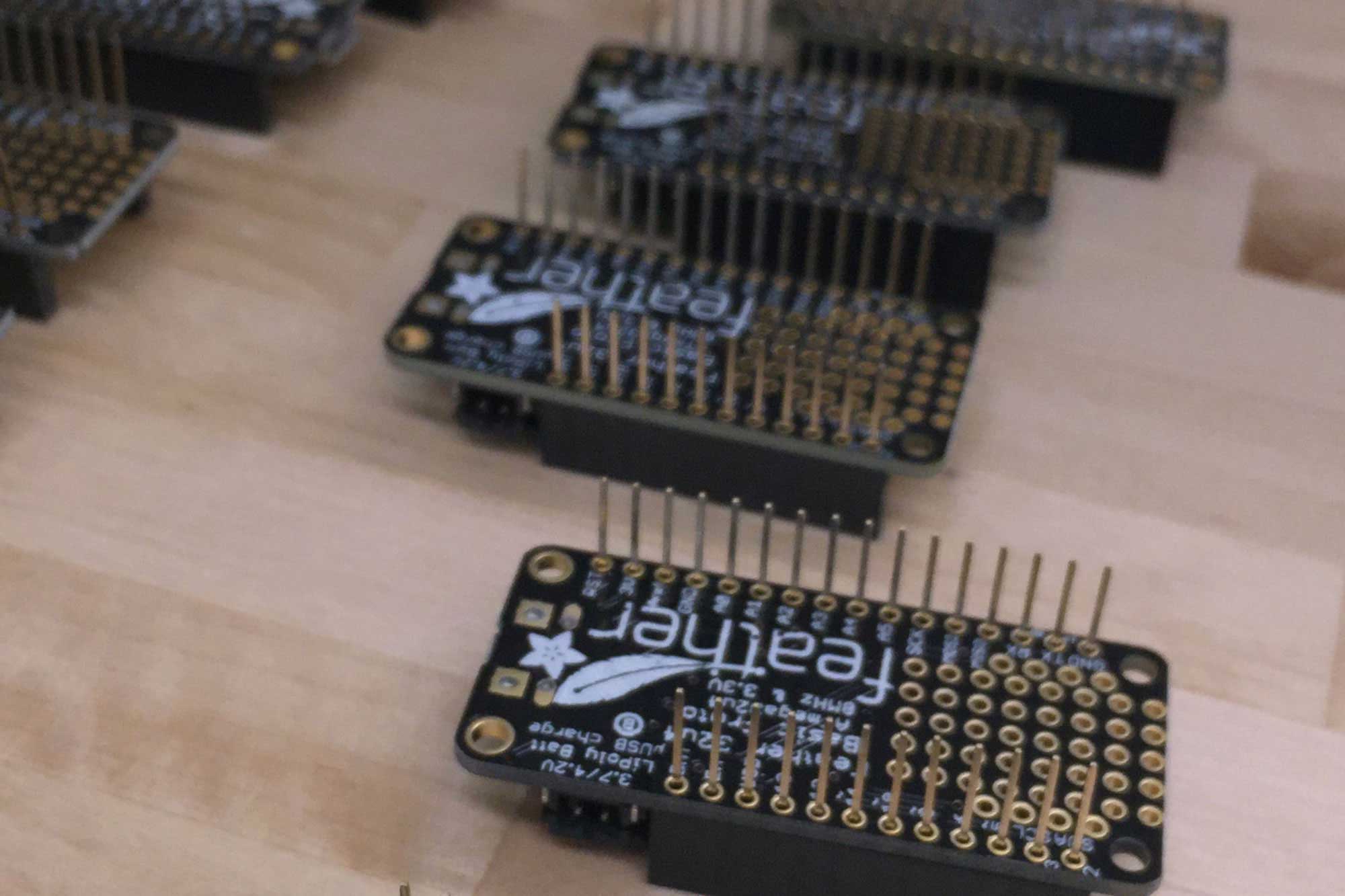

University of Maryland journalists built 80 sensors, with guidance from UMD’s A. James Clark School of Engineering, to monitor extreme summer heat and humidity in Baltimore homes.

The sensors’ structure was modeled after devices used for the Harlem Heat Project, a 2016 investigation by WNYC and AdaptNY. That project found indoor spaces remained intolerably warm throughout the day in the Manhattan neighborhood as temperatures rose and fell outside.

Left: Heat and humidity sensors built by the University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism and students at Wide Angle Youth Media in Baltimore, using labs at the university’s A. James Clark School of Engineering. (Photo by Timothy Jacobsen | University of Maryland) Right: A sensor sits on a shelf in the rowhouse of a Broadway East resident. (Photo by Ian Round | University of Maryland)

John Keefe, a journalist who worked on the project, published open-source code for the construction and use of the technology online, which allowed University of Maryland journalists to build on the work in Baltimore. Each device includes a monitor that includes a small computer, a temperature sensor, a clock, batteries and an SD card, which allows it to record and store information. The sensors were housed in protective 3D-printed cases. They were tested and calibrated for accuracy before deployment.

This summer, nine sensors in seven homes recorded data. Reporters placed one or two sensors in most homes in locations where residents spent significant time. They were installed between knee and shoulder height, away from heat-emitting appliances and windows, where direct sunlight would not artificially increase temperature readings.

The sensors recorded temperature, humidity, date and time about once every minute. University of Maryland journalists returned to the homes, with permission from residents, every few weeks to download information the devices documented and interview the residents about the data findings.

Those sensors recorded indoor temperatures as high as 97 degrees Fahrenheit and heat index values of 119 degrees. The heat index — a combination of temperature and humidity — describes what the air temperature feels like.

Data collected from the sensors showed that for many people who have no central air conditioning or only low-powered window units, their homes don’t cool off that much in the evening, even though the outdoor temperature has decreased. It also showed that for many people, it was frequently hotter indoors than it was outside. In one couple’s home during a heat wave in July, the heat index reached 116 F indoors at 10:30 p.m. — 22 degrees hotter than the heat index outside at the time.

The data

The Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service also analyzed more than a dozen separate data sources for this project, including:

Detailed health records describing inpatient and emergency room hospital visits, as well as emergency medical services response records.

Detailed temperature data, including hour-by-hour historical temperatures at the Inner Harbor and block-by-block temperature data collected by researchers from Portland State University and the Science Museum of Virginia, describing geographic variations in Baltimore’s urban heat island and projections of future temperatures.

Detailed tree data, including a database of trees lining Baltimore’s streets, requests by police to remove or trim trees, a snapshot of Baltimore’s urban tree canopy in 2007 and 2015 created by researchers at the University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab and the U.S. Forest Service, and more recent canopy data created by researchers at Descartes Labs.

Detailed demographic and housing data from the U.S. Census and other sources detailing poverty, income, crime, historical mortgage lending patterns and vacant houses.

On-the-ground reporting

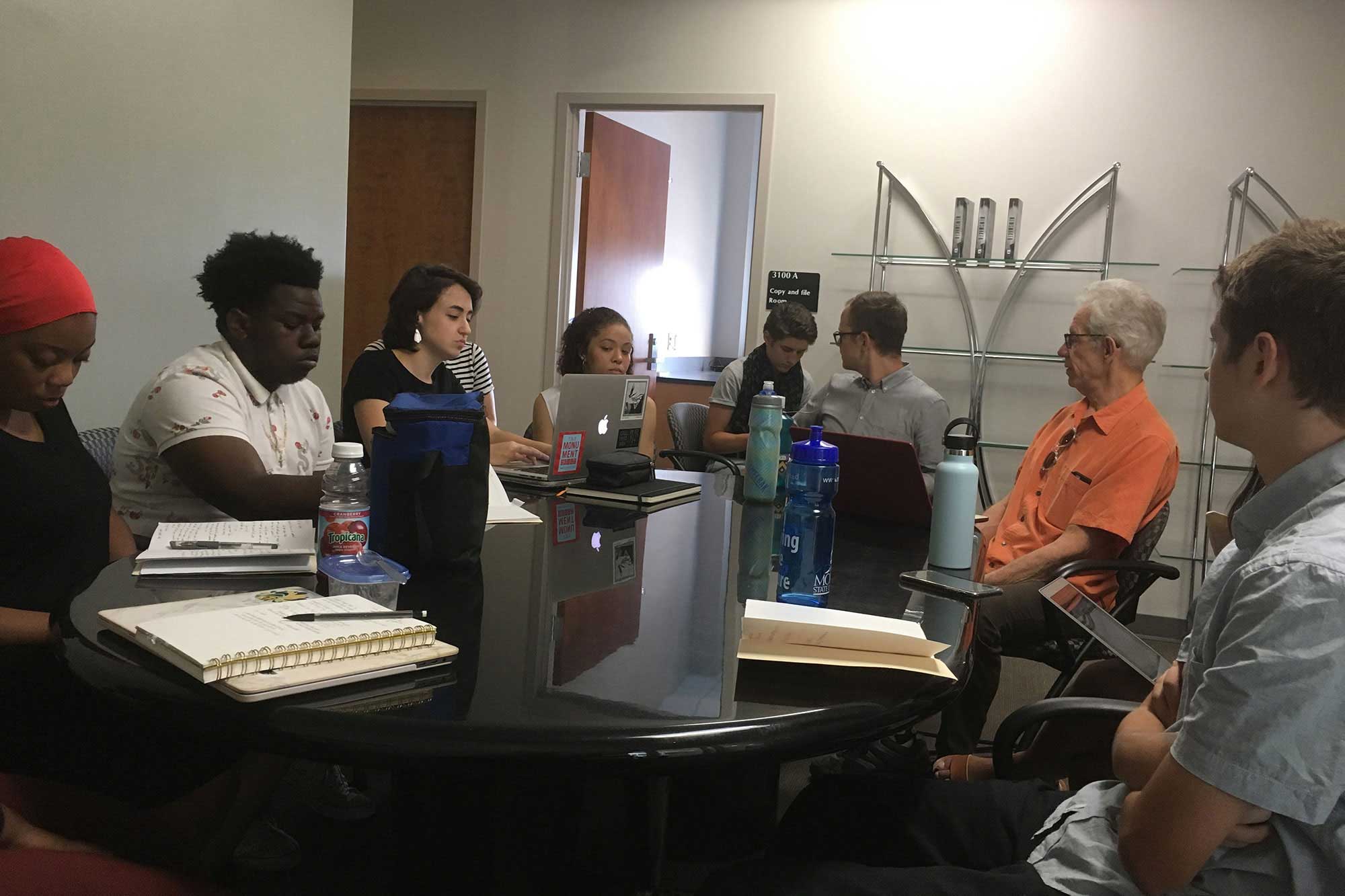

University of Maryland reporters and photographers spent 10 weeks in neighborhoods identified as some of the hottest in Baltimore. A team of 10 reporters interviewed residents of McElderry Park, Broadway East and other neighborhoods about their health conditions, their daily lives and what they do to combat high heat. The reporters also interviewed emergency room doctors, public health leaders, city and state officials, climate scientists, urban foresters, tree-planting crews, and church leaders.

Two University of Maryland photographers worked with photographers from Wide Angle Youth Media, a nonprofit based in Baltimore that teaches visual storytelling to young people. Together, they documented life on the streets and inside residents’ homes during the long, hot summer. A freelance journalist shot drone video to illustrate the tree canopy and the lack of reflective surfaces on roofs in the area.

Faculty and staff members with decades of professional journalism experience oversaw the work.

The Howard Center, Capital News Service and partners

The Howard Center for Investigative Journalism launched this year through a grant from the Scripps Howard Foundation. The multidisciplinary program gives Merrill College students the opportunity to work with news organizations across the country to report stories of national or international importance to the public.

Capital News Service is a student-powered news organization run by the University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism. For almost 30 years, CNS has provided award-winning coverage of issues important to Marylanders.

Read the first installment of this investigation into the effects of climate change on public health in Baltimore, "Bitter Cold."

For this investigation, the Howard Center and CNS partnered with NPR, WMAR television and Wide Angle Youth Media, a Baltimore nonprofit that teaches digital media skills to young people ages 10 to 24.

Support for this project comes from generous grants from the Scripps Howard Foundation, the Park Foundation, the Online News Association, the Annie E. Casey Foundation and the Philip Merrill College of Journalism.

Credits

Reporting and writing: Jazmin Conner, Theresa Diffendal, Bryan Gallion, Kaitlyn Hopkins, Dan Novak, Xander Ready, Ian Round, Jermaine Rowley, Sandy Banisky, John Fairhall and Sean Mussenden

Photography: Amina Lampkin, Maris Medina, Timothy Jacobsen and Ian Round

Graphics: Amina Lampkin, Maris Medina, Xander Ready, Camila Velloso, Adam Marton, Sean Mussenden and Krishnan Vasudevan

Design and development: Camila Velloso and Adam Marton

Data analysis: Theresa Diffendal, Xander Ready, Jane Gerard, Jake Gluck, Adam Marton and Sean Mussenden

Video: Amina Lampkin, Maris Medina, Nate Gregorio and Timothy Jacobsen

Editing: Brooke Auxier, Sandy Banisky, Kathy Best, John Fairhall, Timothy Jacobsen, Martin Kaiser, Adam Marton, Sean Mussenden, Alex Pyles and Krishnan Vasudevan

Social Media:Brooke Auxier, Bryan Gallion, Brittany Goodman, Kaitlyn Hopkins and Alex Pyles

NPR: Meg Anderson, Nora Eckert, Sean McMinn and Robert Little

Wide Angle Youth Media: Emma Bergman (Editing), Katia Crawford, Justice Georgie, Sonia Hug, Justin Marine and Otto Blais-Nelson