Bringing Trees To Broadway East

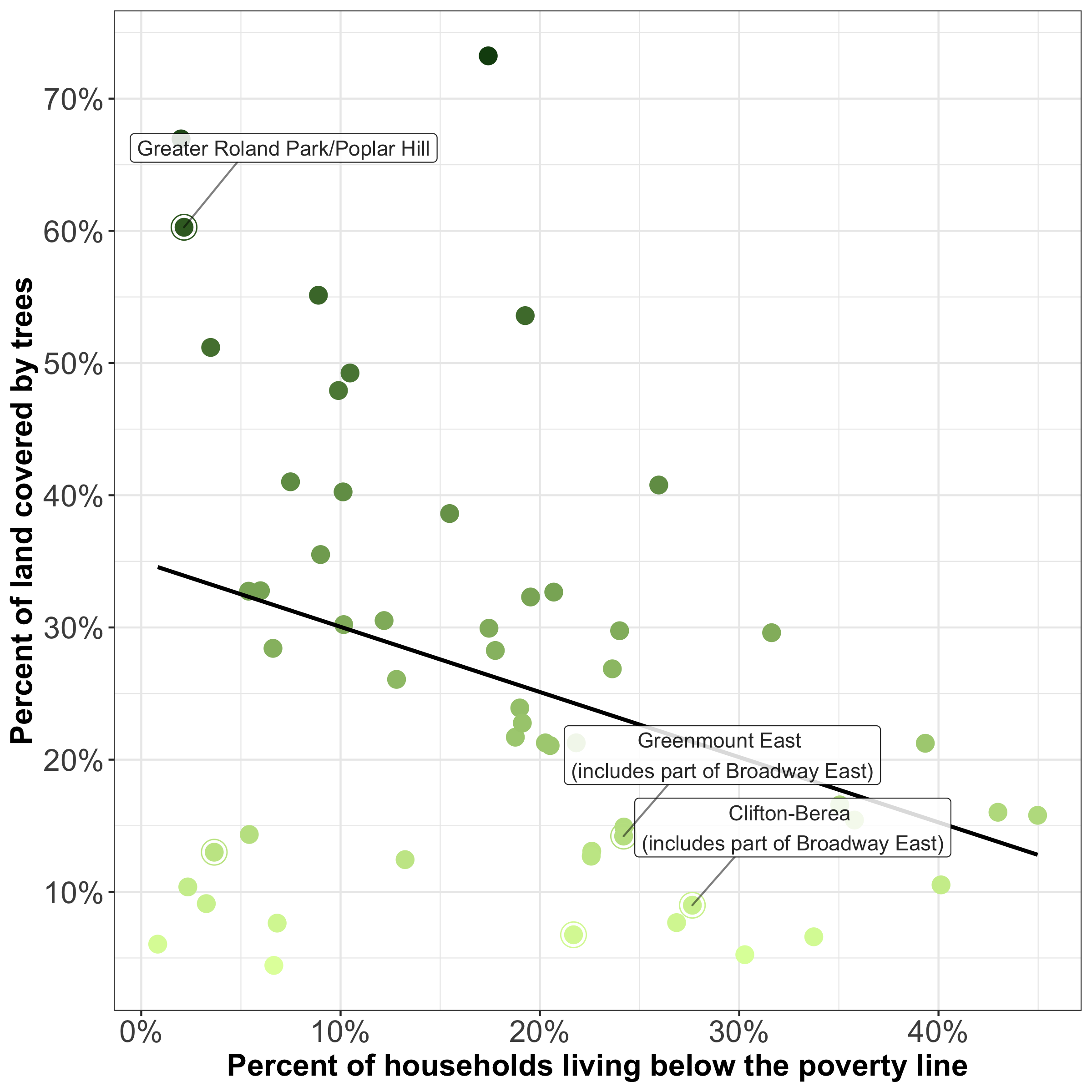

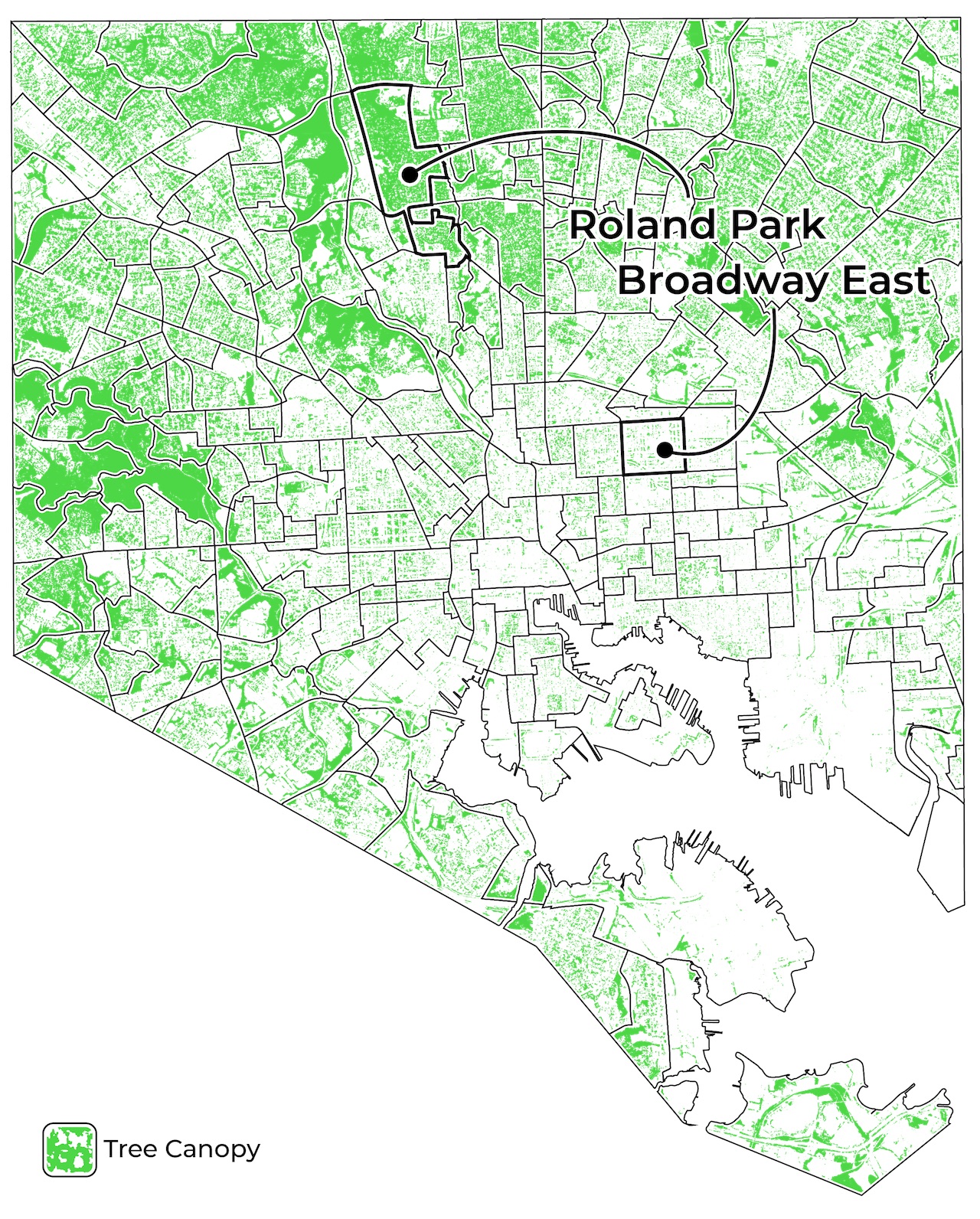

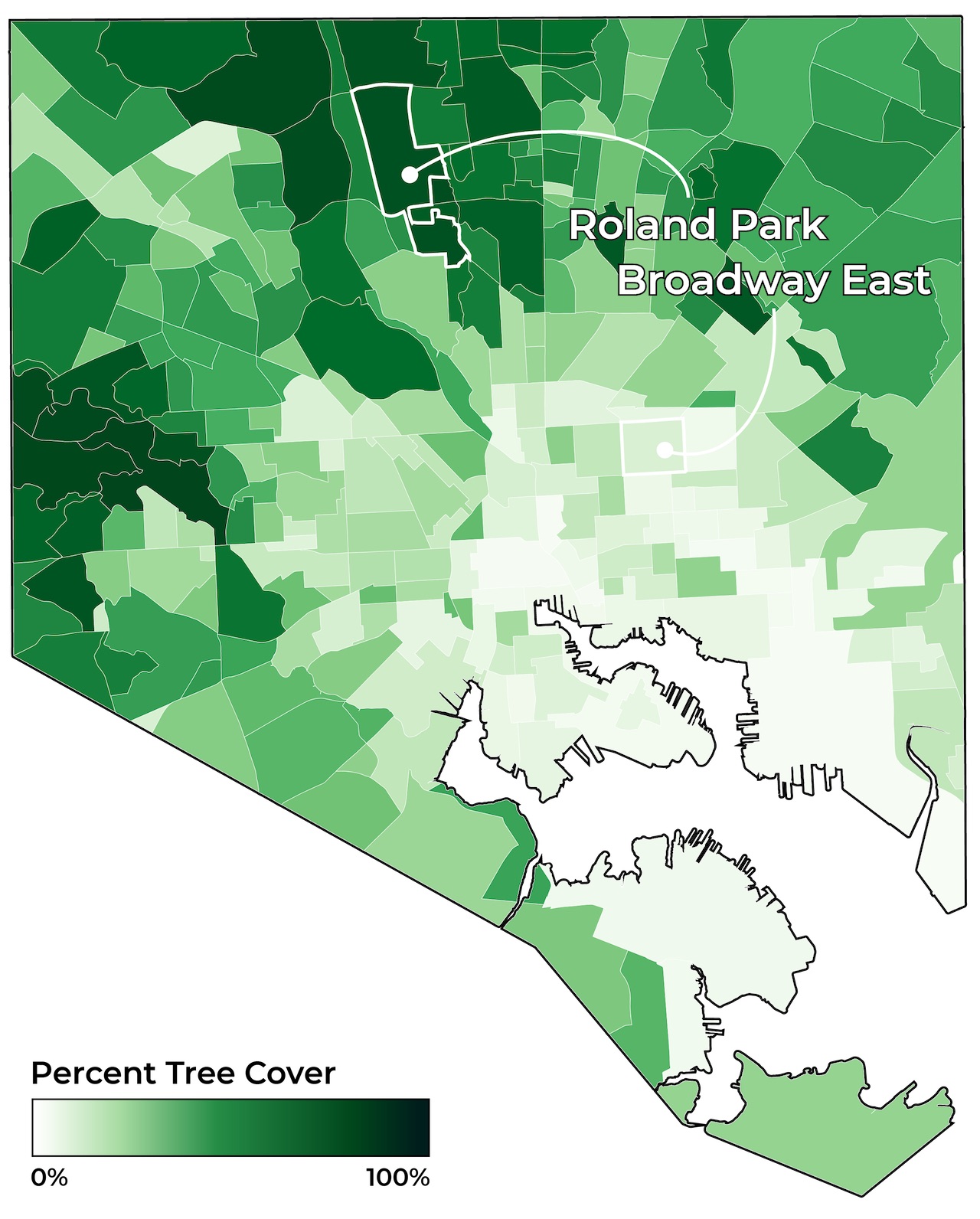

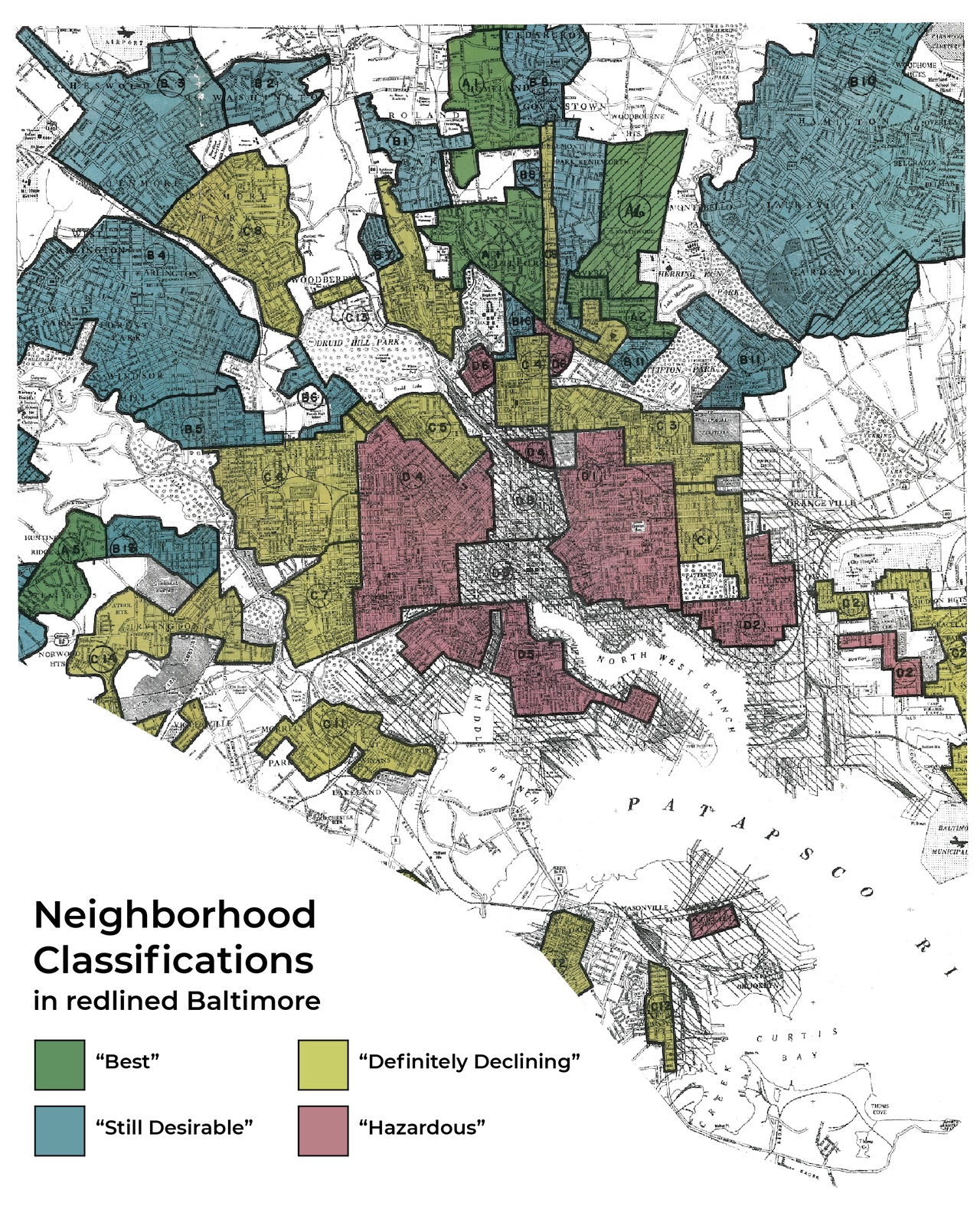

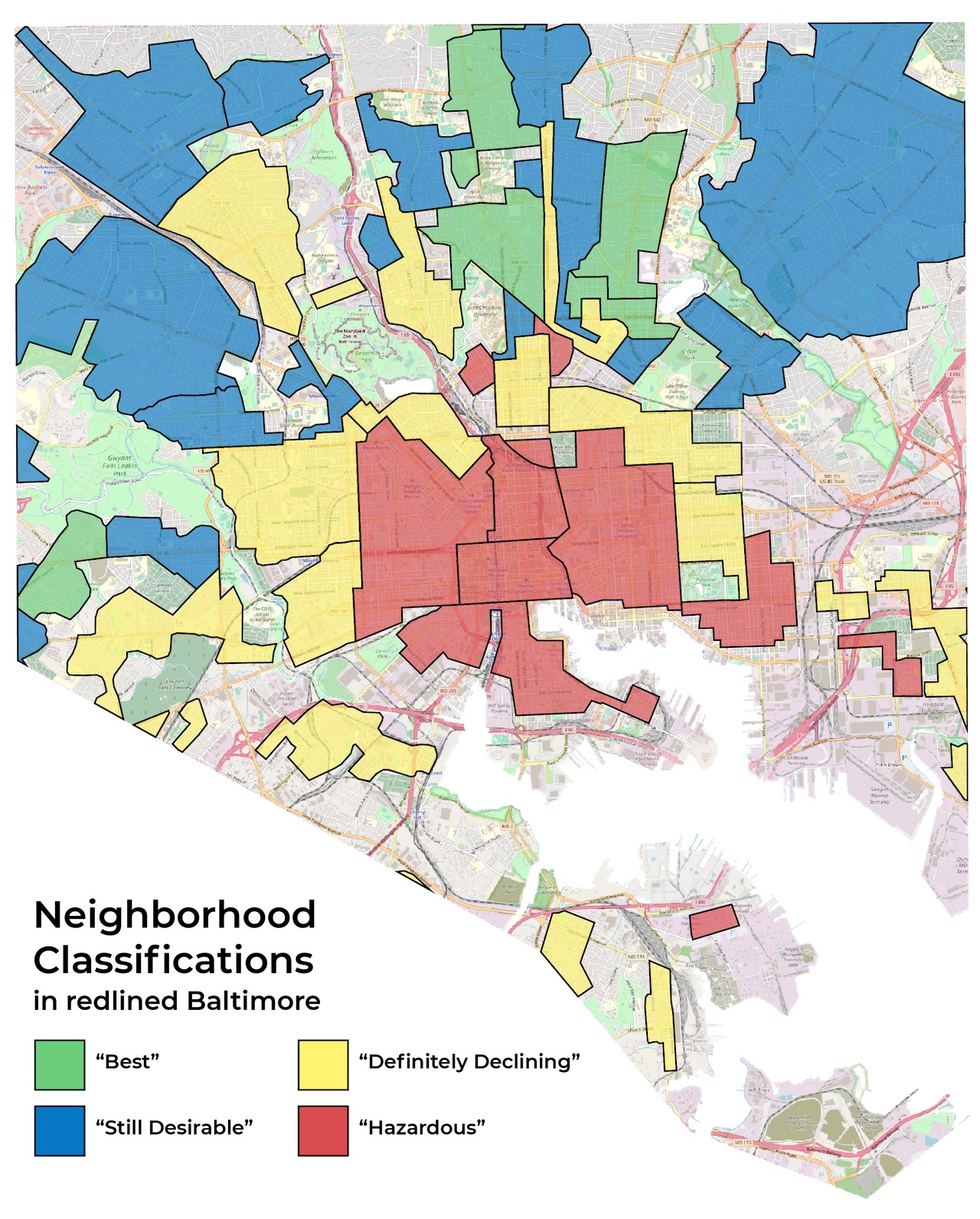

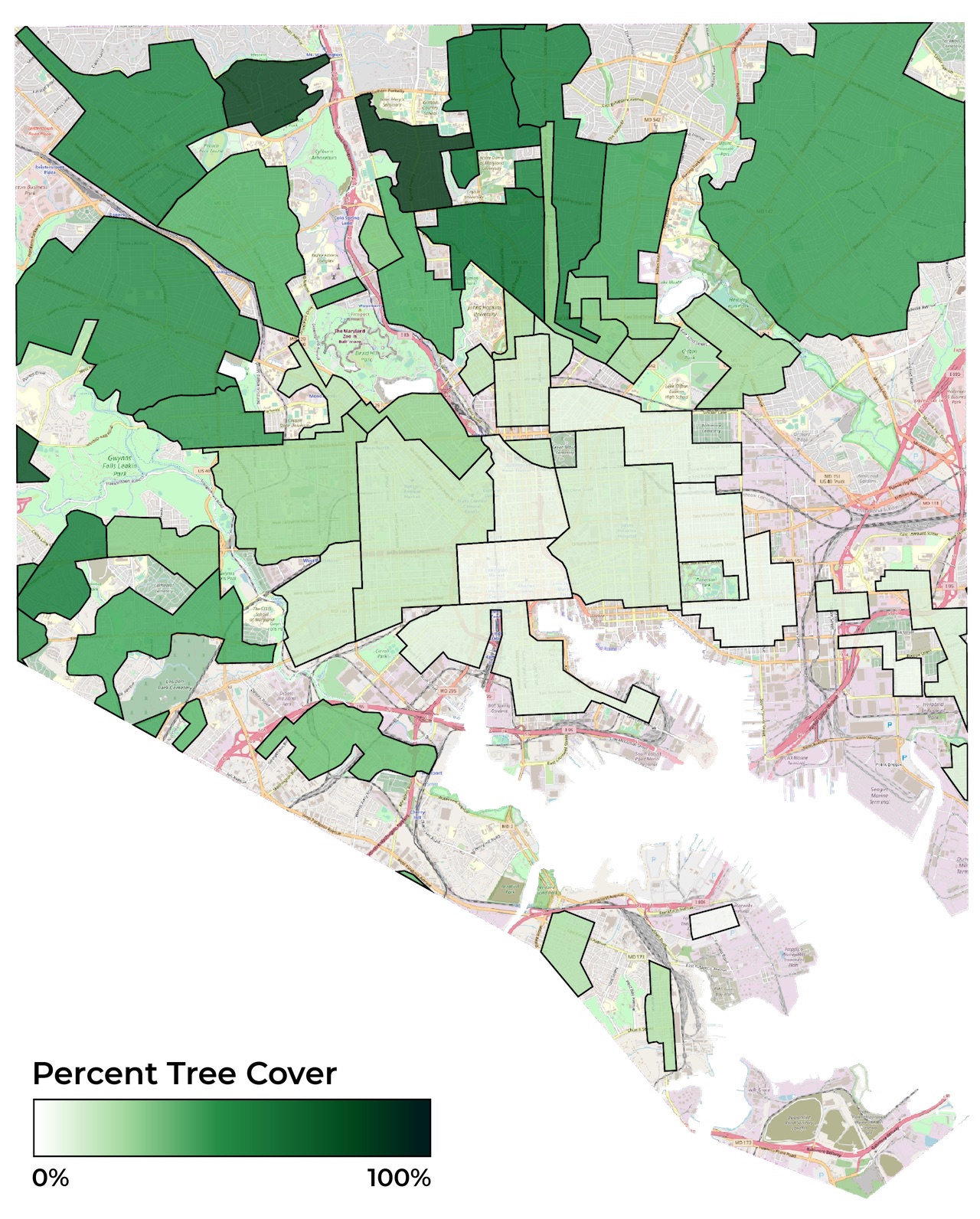

Tree canopy coverage of 40% is, officially, the citywide target the forestry division hopes to hit by 2037. Baltimore was at 28% in 2015, up from 27% in 2007, according to researchers with the U.S. Forest Service and the University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab, who created the two most recent precision assessments of the city's tree canopy.

The city’s forestry division and Grove estimate that the current citywide tree canopy still hovers around 28%.

Collectively, the city and nonprofits would need to plant about 25,000 trees per year, up from the current rate of about 10,000 a year, to hit 40% by 2037. And doing that would require a lot more tree planting on private land, over which the city has no control.

Erik Dihle, the city’s arborist and head of the forestry division, said he was proud of the city’s 1 percentage point overall increase. But, he said, “At [the current] rate, we’re not going to make 40% canopy cover.”

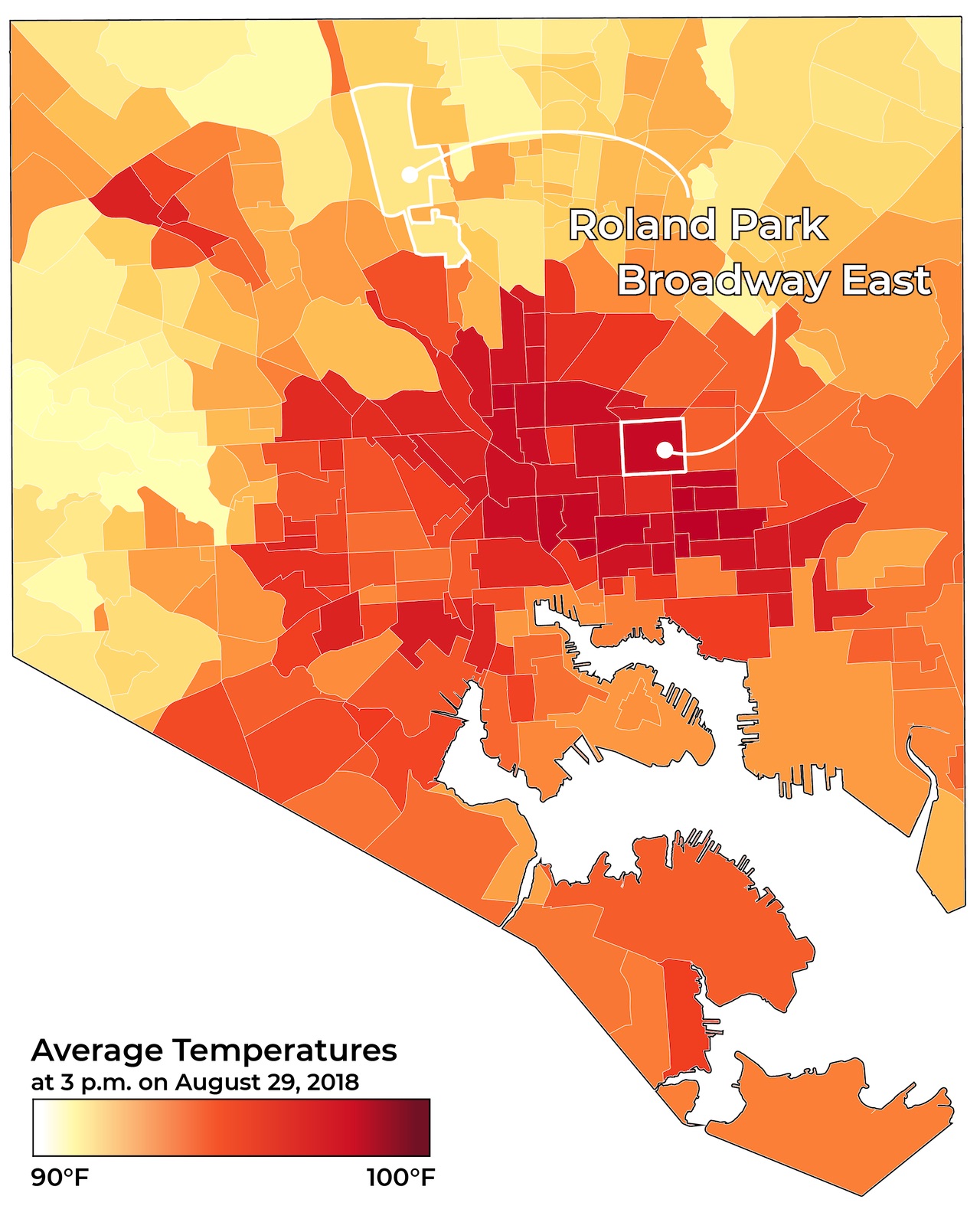

At the level of individual blocks, 40% canopy cover may also be a magic number for heat. In a 2019 study on the relationship between tree canopy and temperature, researchers at the University of Wisconsin and Concordia University found that at least 40% canopy cover was needed to achieve the most significant temperature reductions.

Even with a flurry of planting in recent years, Broadway East and other hot East Baltimore neighborhoods are nowhere near that level and won’t get there anytime soon — if ever.

Trees are an effective cooling solution, but are not a quick fix. They start small, and take years — in some cases, decades — to provide enough shade to significantly move the temperature needle. That’s a big reason canopy growth has been relatively measured despite recent planting efforts.

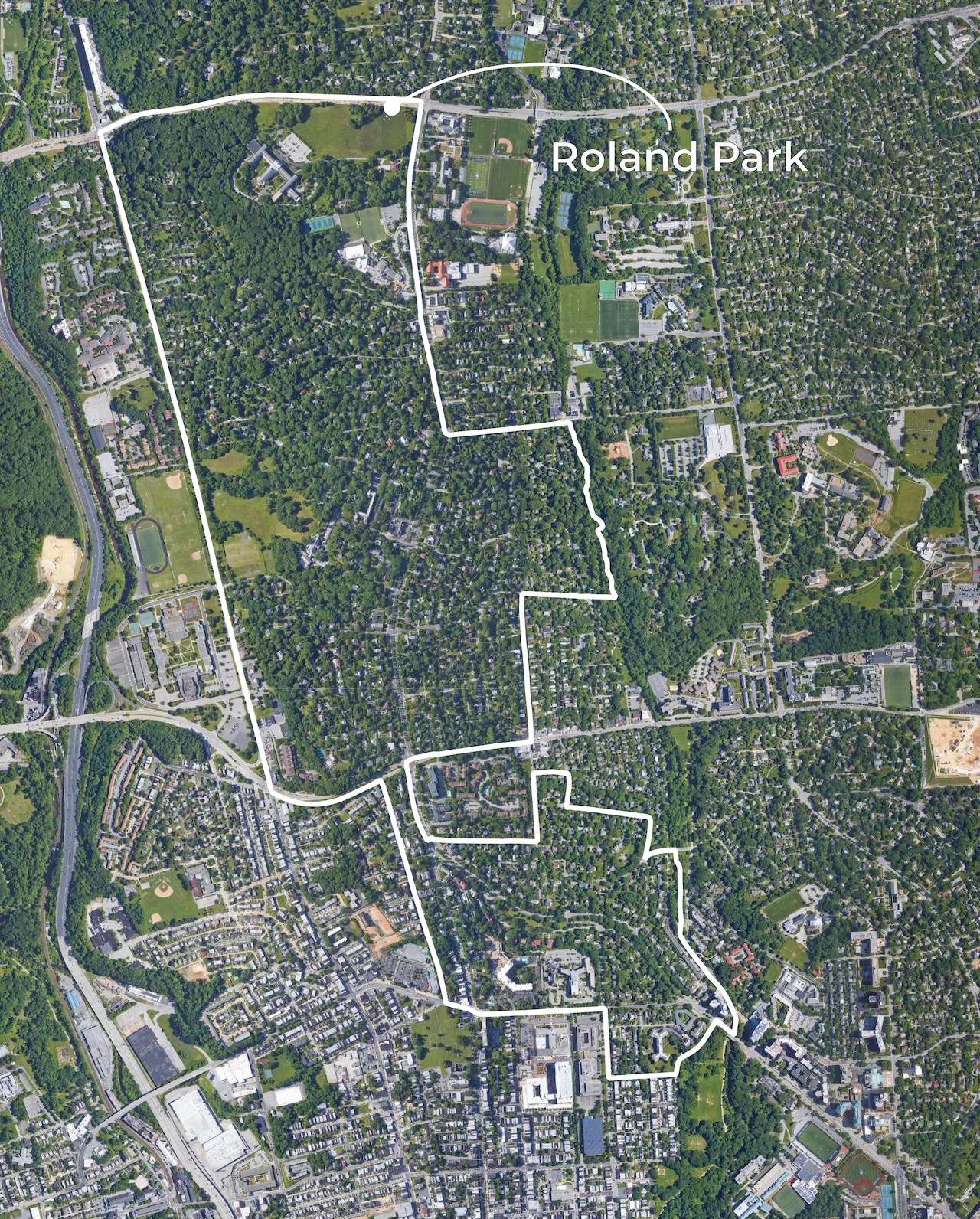

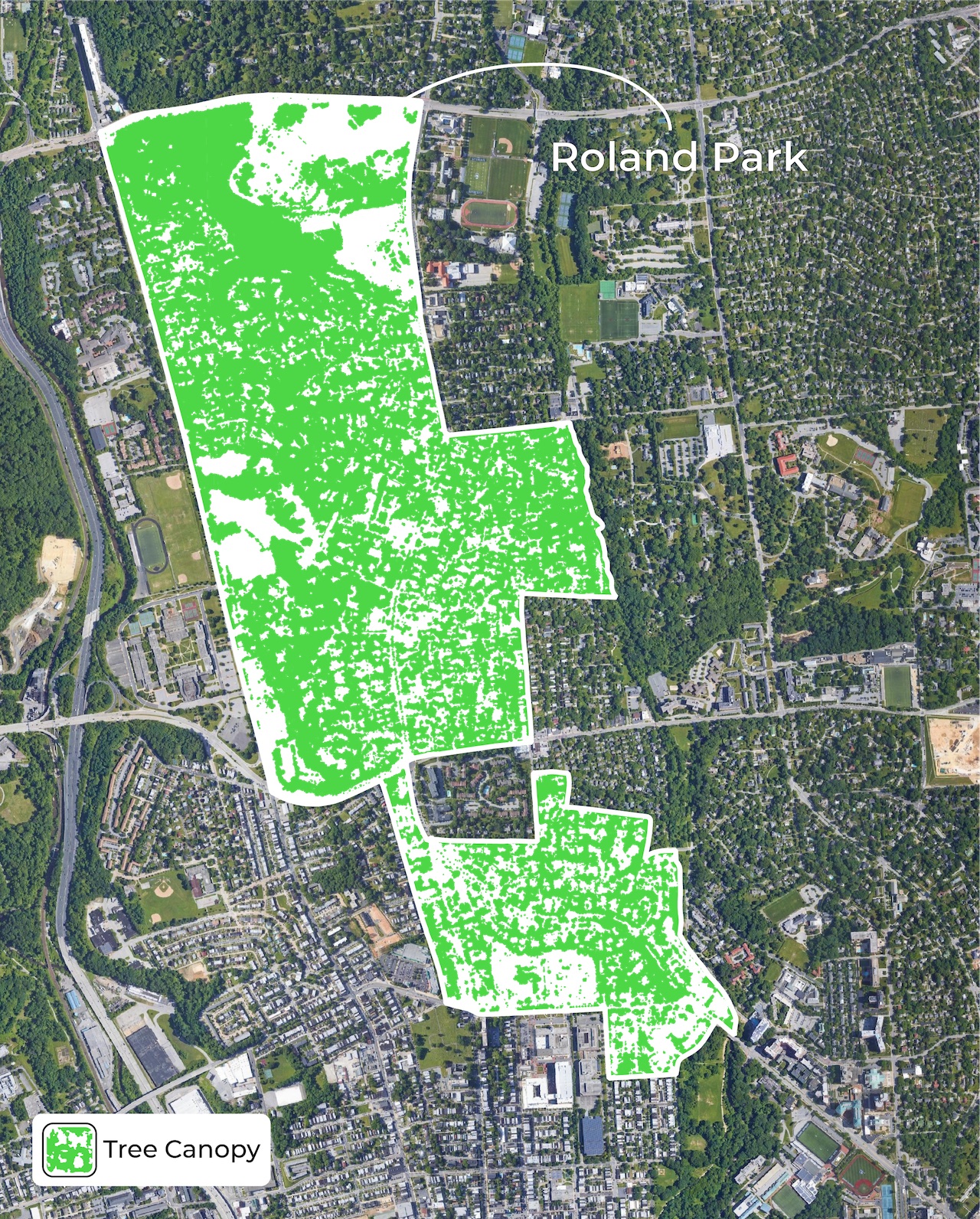

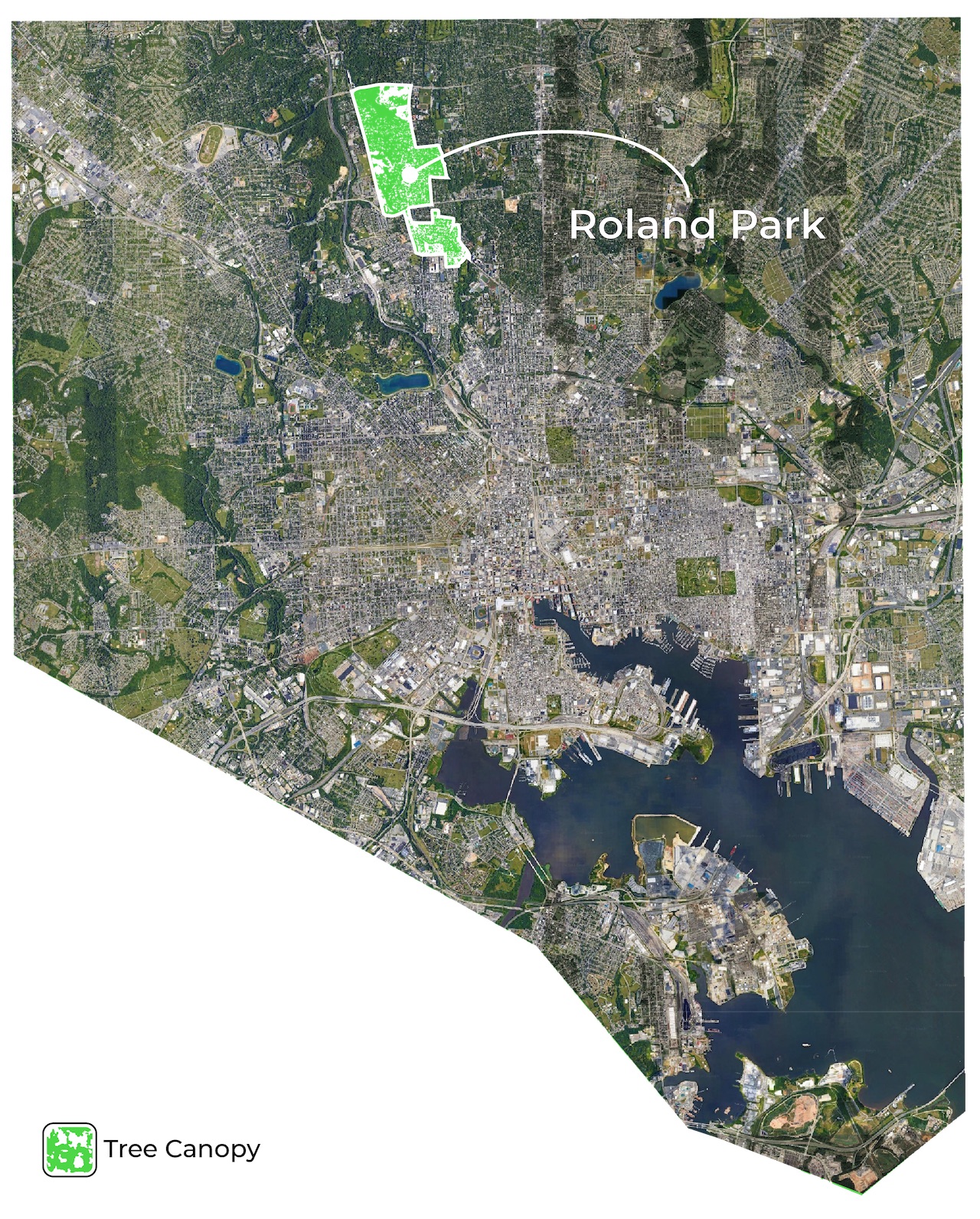

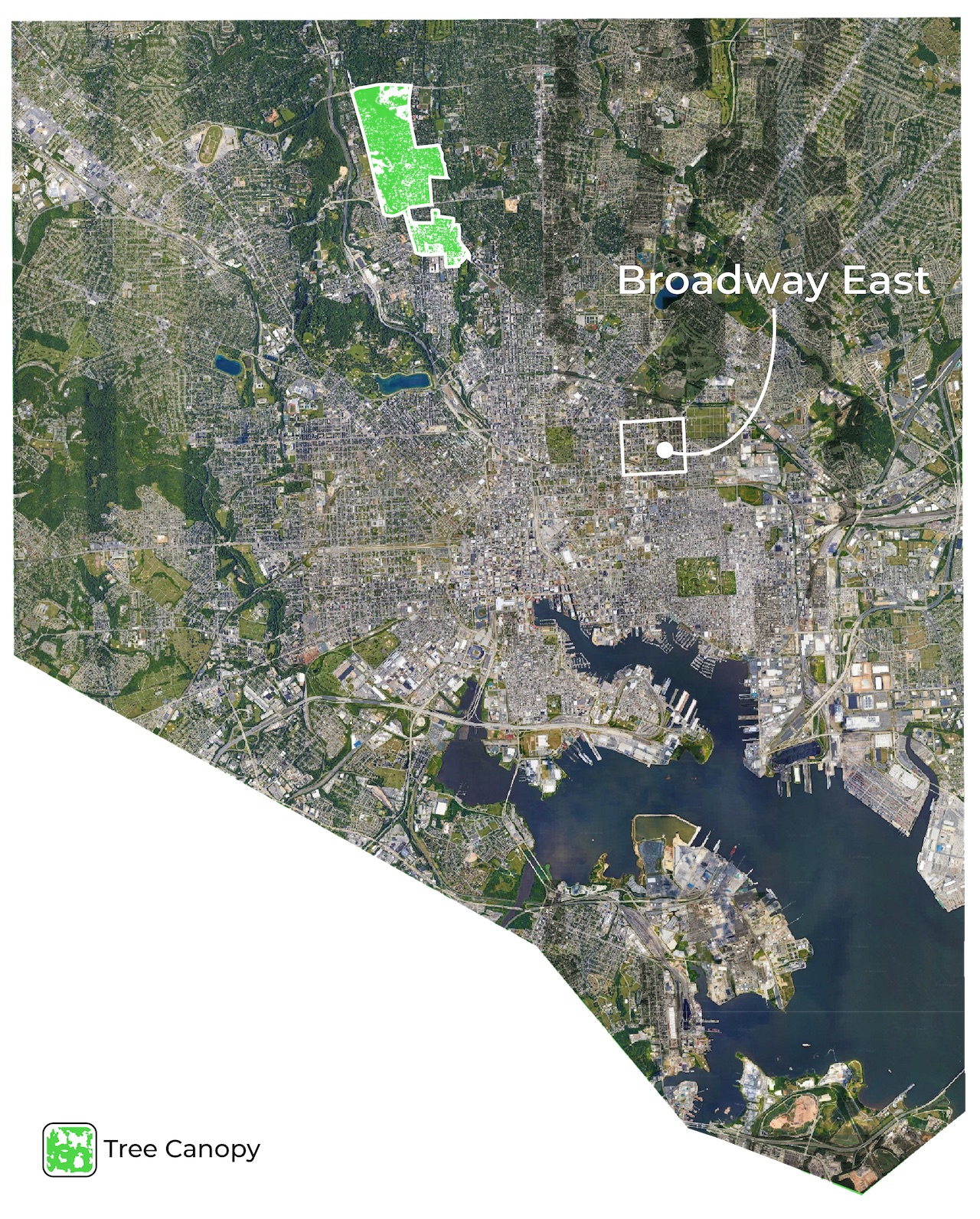

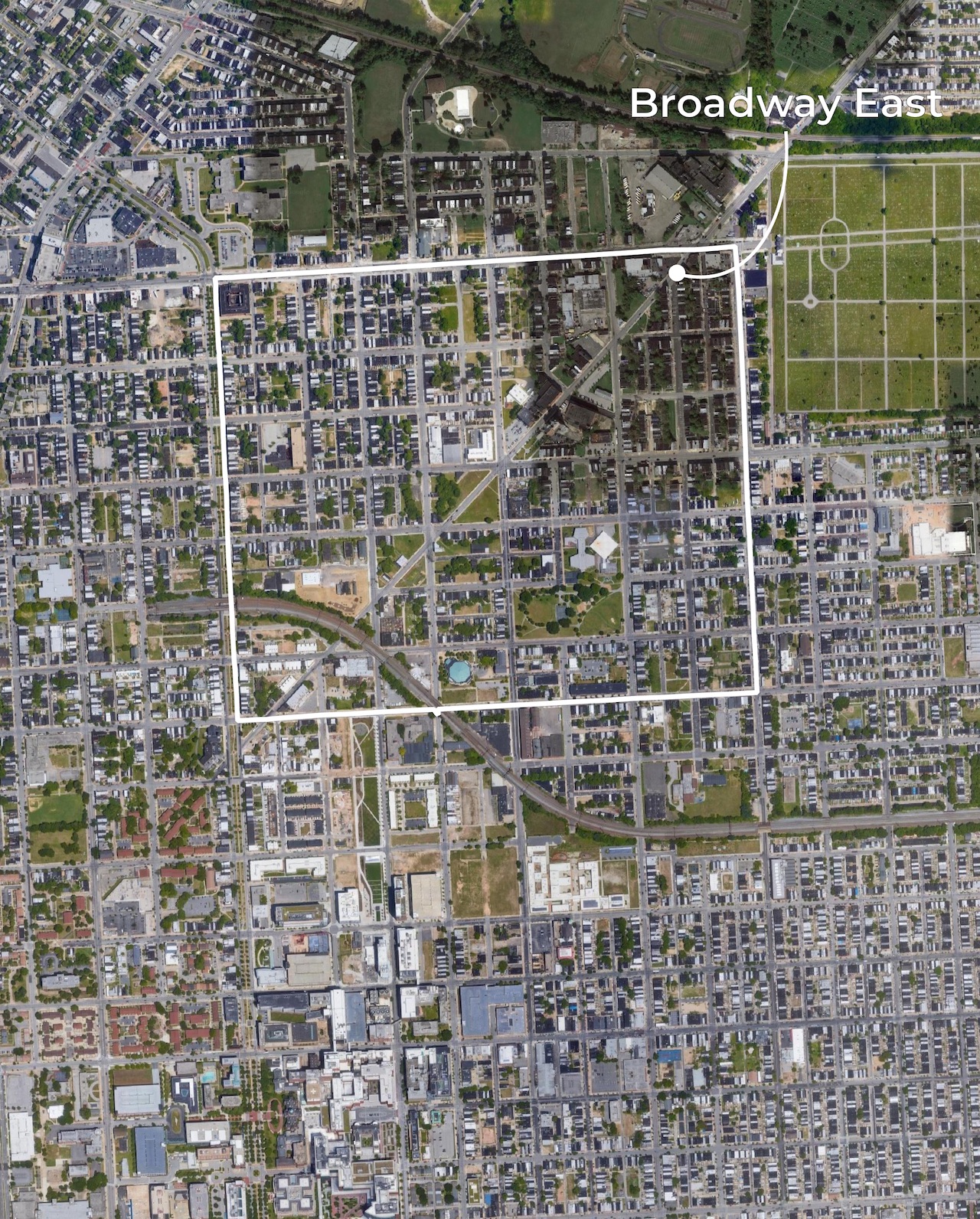

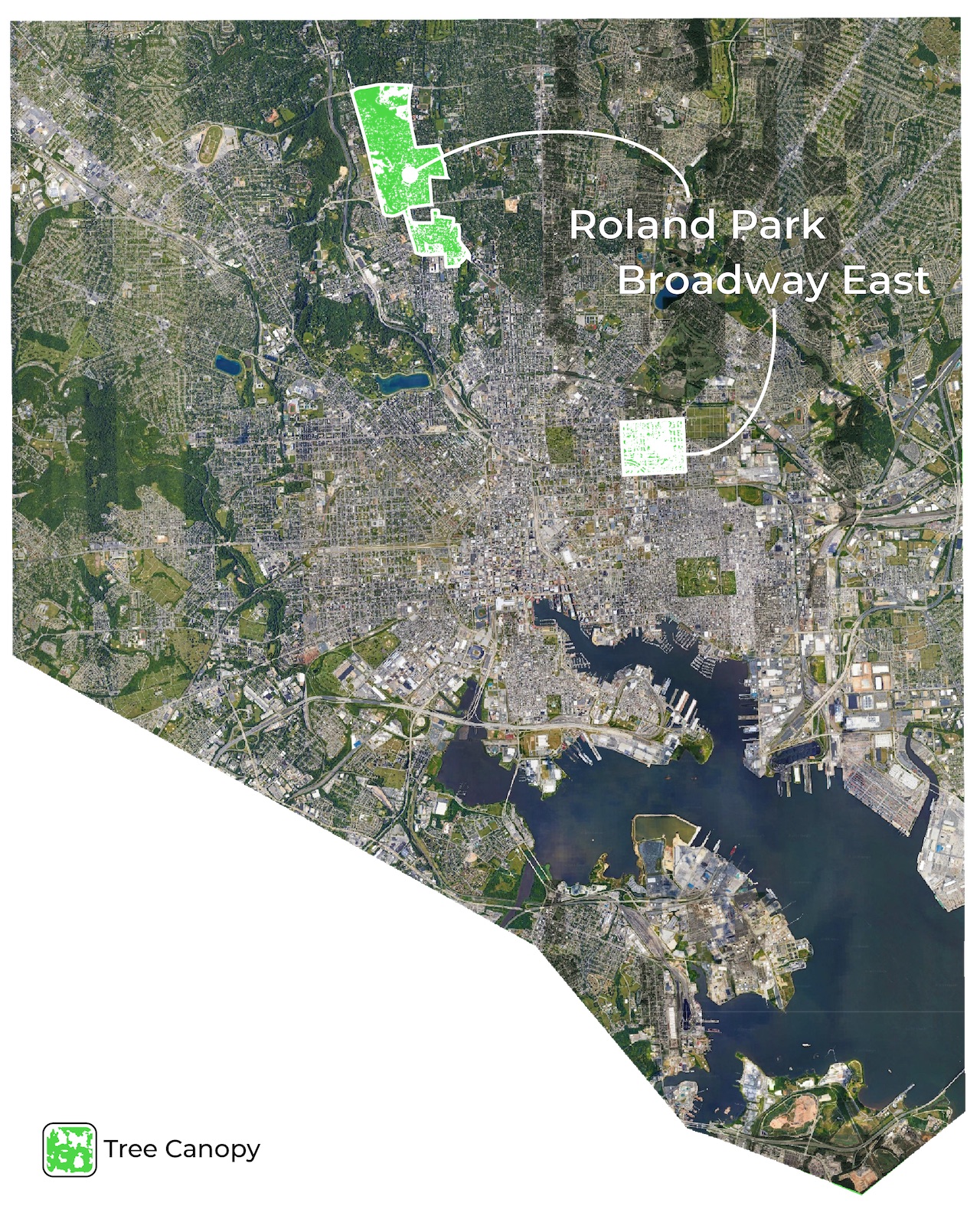

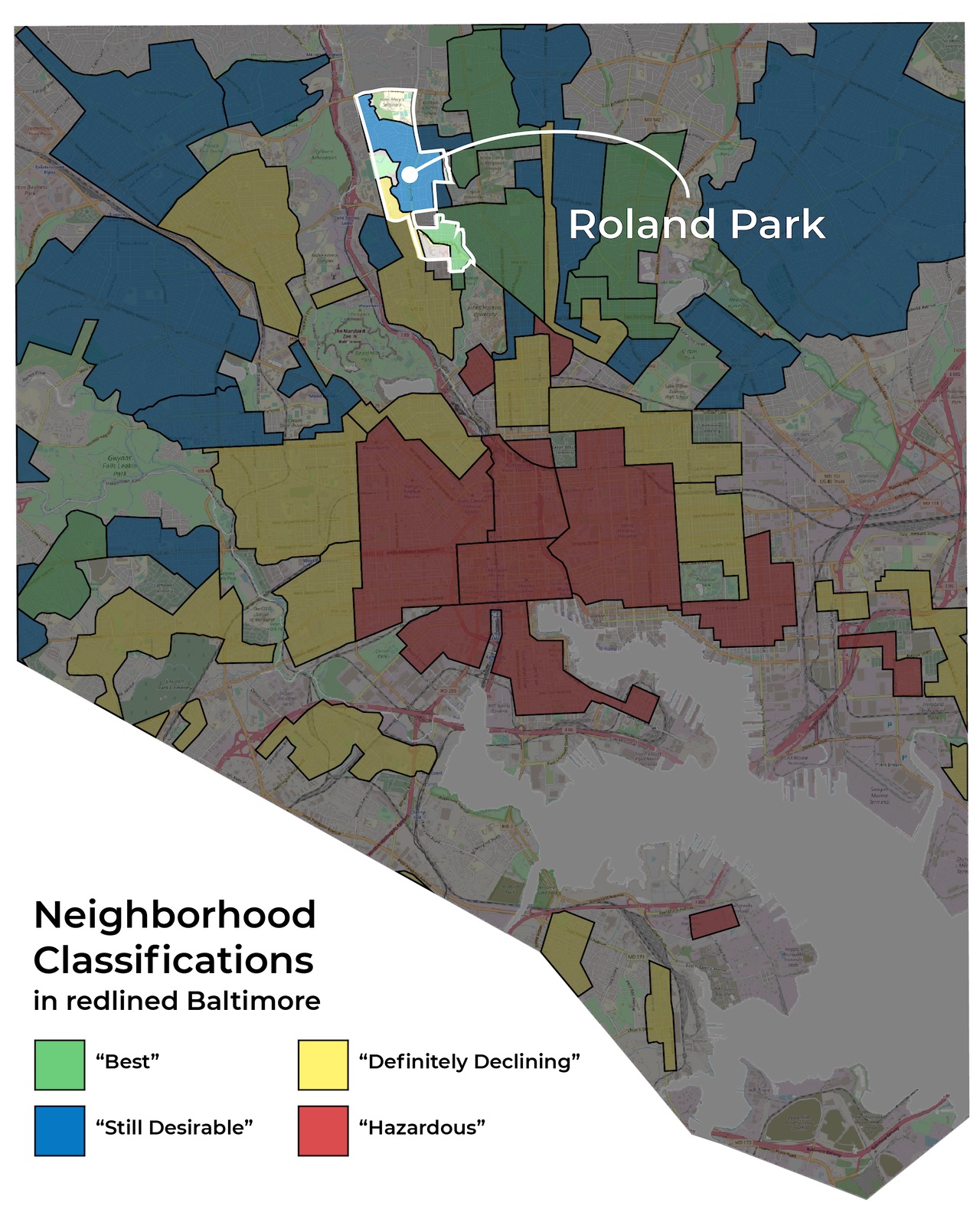

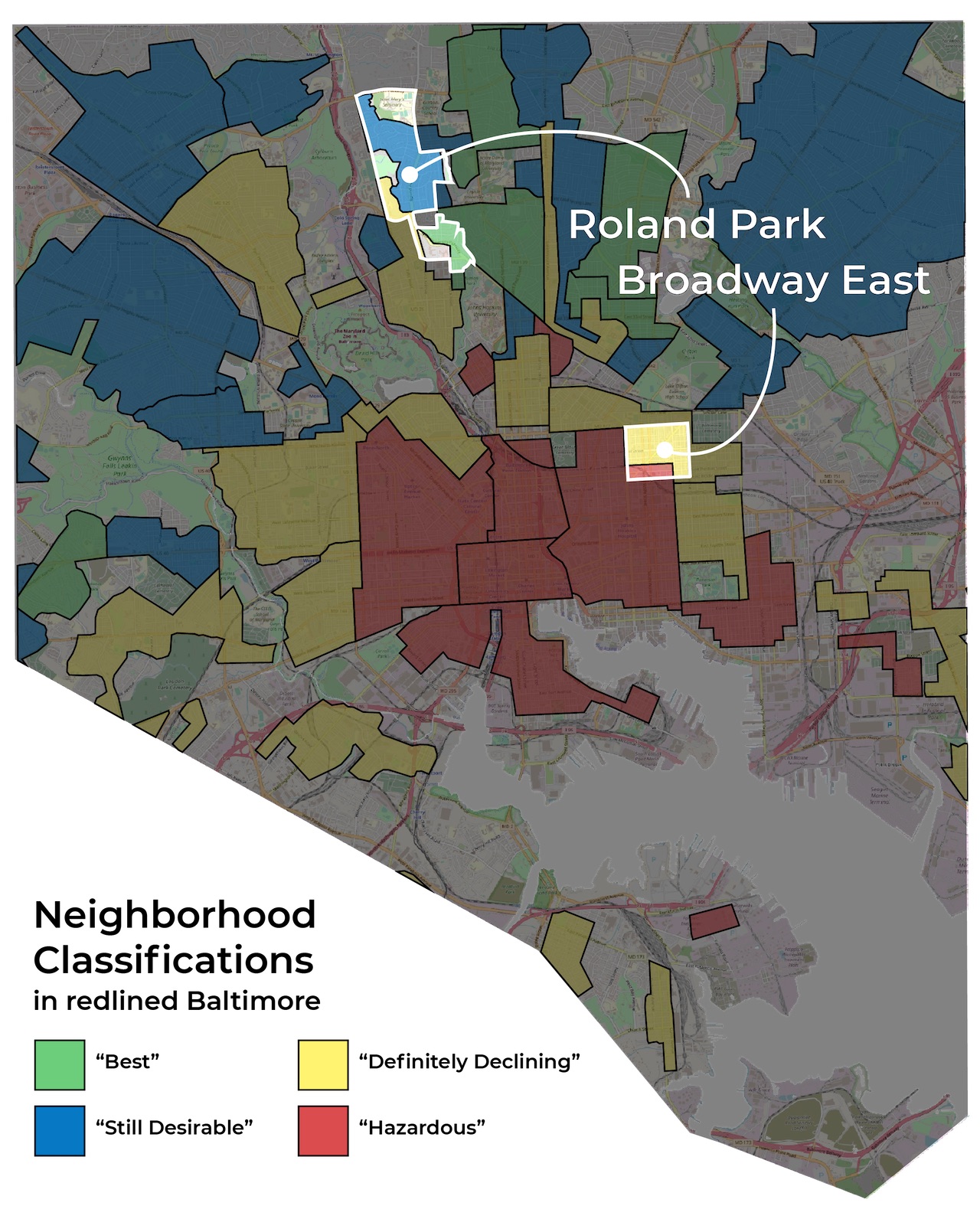

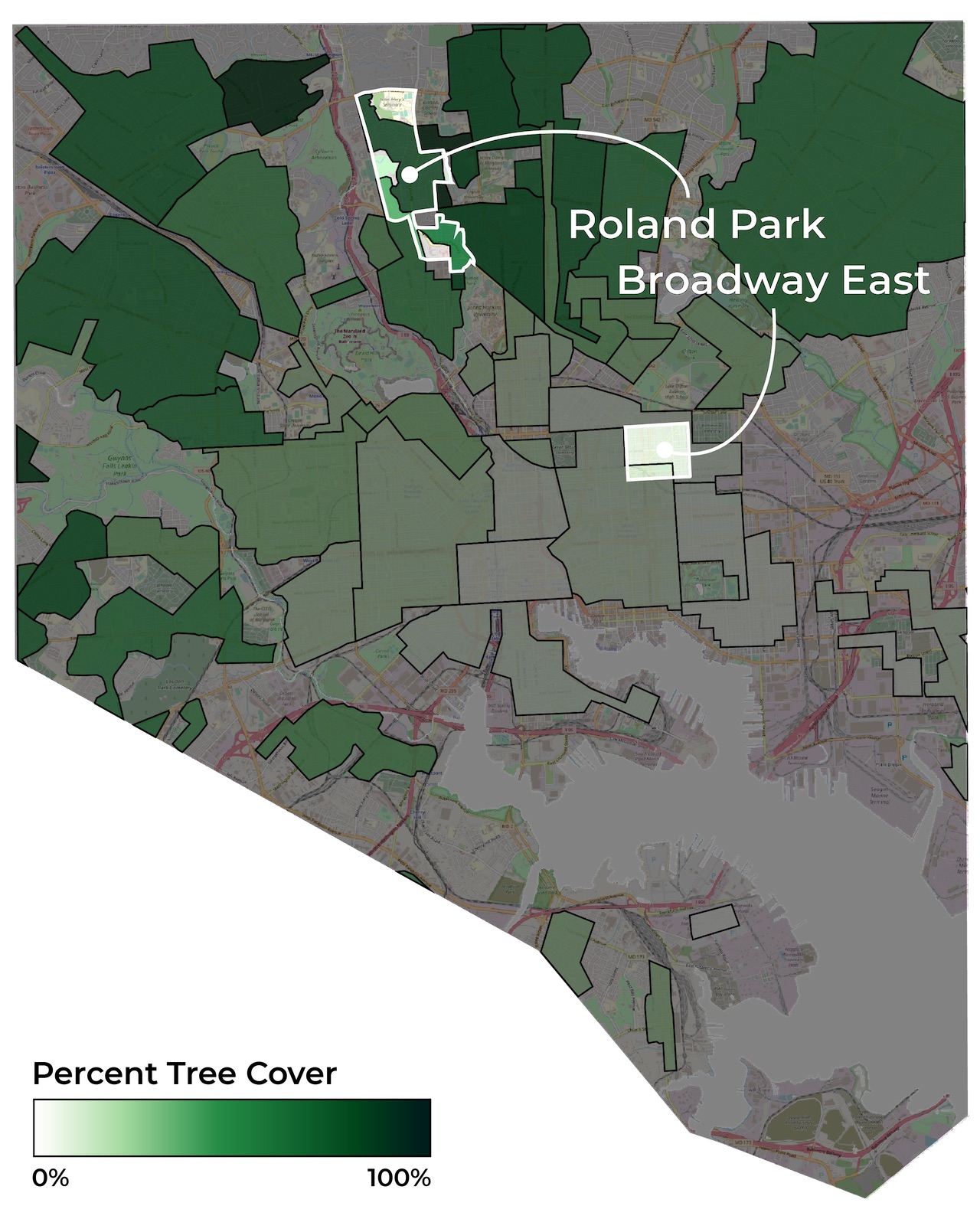

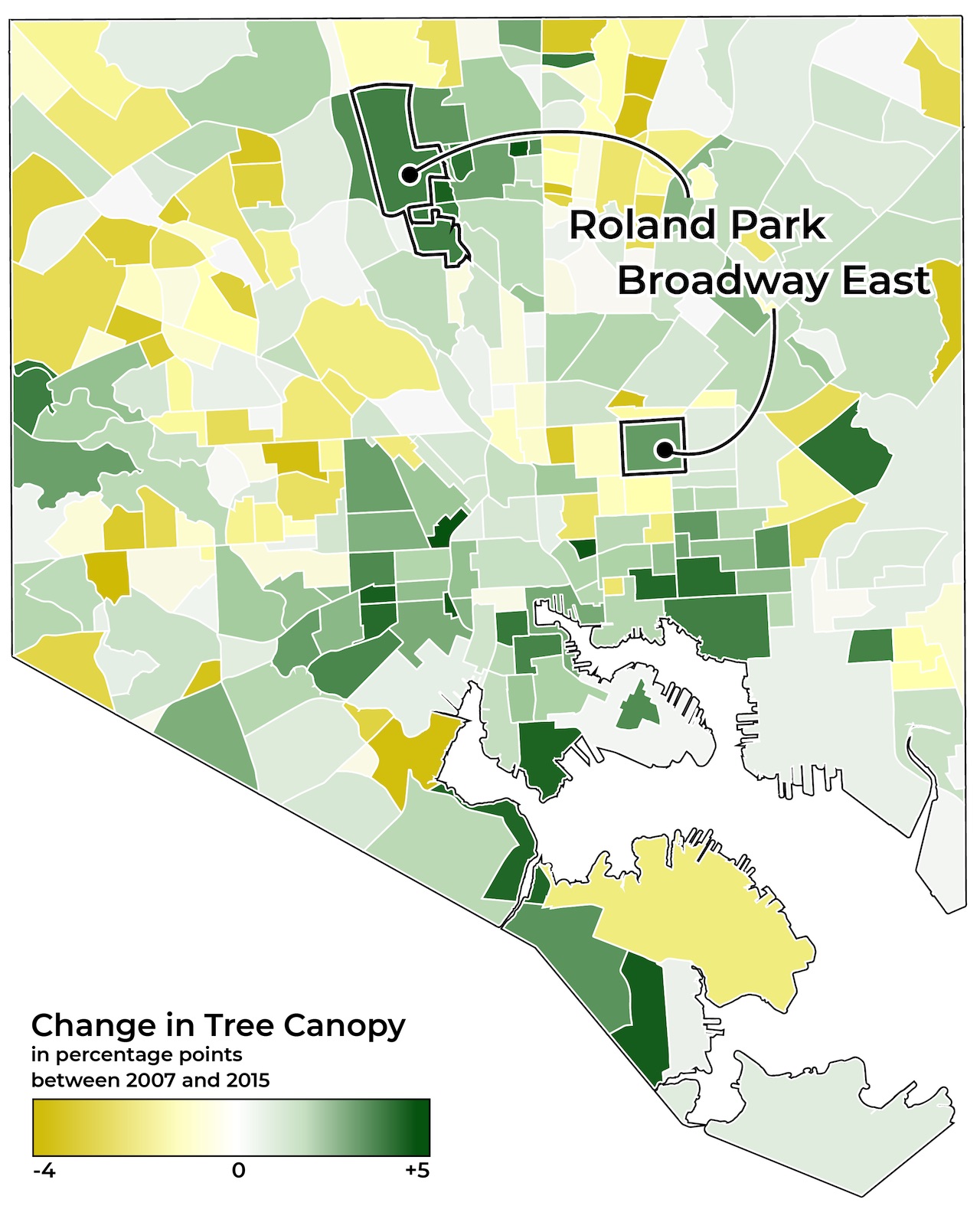

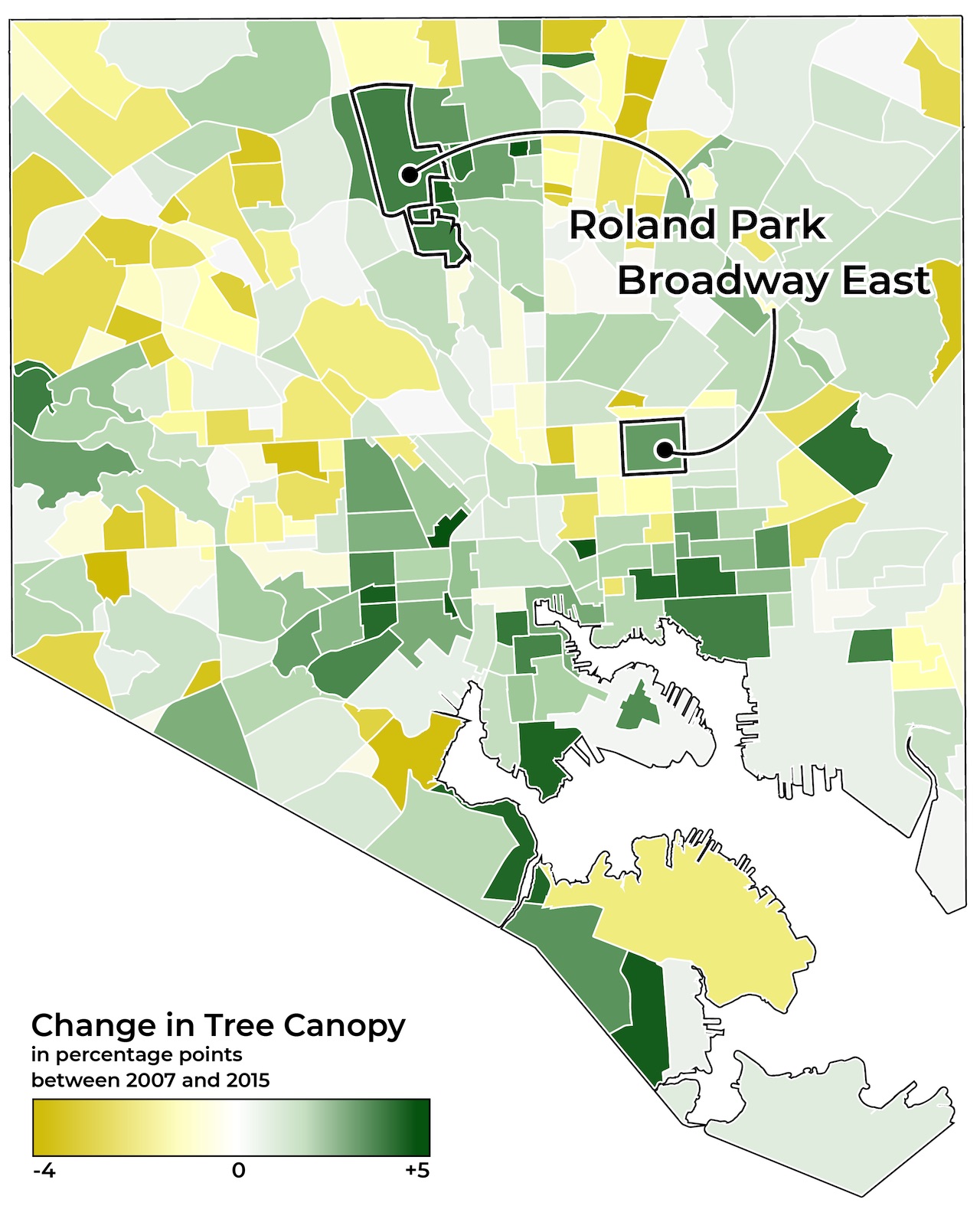

Between 2007 and 2015, tree canopy in Broadway East grew 1.6 percentage points, from 9% to 10.6%, over those eight years. Roland Park, already covered with trees, grew by 2.1 percentage points.

Tree Canopy Change in Broadway East

Between 2007 and 2015, the two most recent years in which Baltimore's tree canopy was assessed by researchers, the canopy in Broadway East grew from 9% coverage to 10.6%. There were losses and gains, but the overall increase was 1.6 percentage points, one of the biggest jumps in the city. Slide the bar to see how the tree canopy changed.

BY XANDER READY

Source: Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service analysis of tree canopy data via U.S. Forest Service and University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab.

The city’s tree canopy is fluid like this. It grows when new trees are planted and existing trees grow larger. It shrinks when trees are trimmed back — or even removed — to accommodate city life, when limbs fall during storms, or trees die from disease or other causes.

“Baltimore is one of those few places where the growth and the planting has outpaced the loss,” Grove said.

Those gains and losses were not distributed equitably. About 40% of city neighborhoods had net losses. The rest had net gains, but the increases in Baltimore's hottest neighborhoods didn't come close to correcting the inequity.

CHANGE IN TREE CANOPY

Both Roland Park and Broadway East showed increases in tree canopy from 2007 to 2015.

BY XANDER READY

Source: Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service analysis of tree canopy data via U.S. Forest Service and University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab.

For Daley, of American Forests, a city’s overall level of canopy cover is less important than the numbers in each neighborhood — and the differences between them.

“A simple percentage for the whole city … can mask those inequities,” he said. “Whatever the right level of tree canopy is for a given city, given its climate and its setting, we should hit that same mark in every single neighborhood. And we have a lot of work to do to bring, particularly, low-income neighborhoods and communities of color up to that citywide standard.”

Maximum Canopy “Not Practical”

As director of operations and community outreach for the Baltimore Tree Trust, Alex Smith helps determine what trees to plant in specific spots in neighborhoods like Broadway East — a red maple on this block, a London plane on that one.

Alex Smith, director of operations at the Baltimore Tree Trust, says the city has so many competing problems that it’s hard to get people to focus on trees. (Photo by Maris Medina | University of Maryland)

His job takes him all over the city and he’s been down streets in Roland Park where giant trees crane over from both sides, forming a living archway of impenetrable canopy over the road.

“It’s shaded. It’s beautiful. It’s almost majestic,” he said. “Somebody designed that. And they could see, when those trees were small, that one day you could drive down [the street], and there’s no way you couldn’t feel the effect of these trees.”

There are no streets like that in Broadway East, and creating them would be impractical, Smith said.

On many blocks, the sidewalks are too narrow to accommodate a tree of sufficient size and allow enough room for people in wheelchairs in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Large roots that crack and elevate sidewalk sections also create accessibility problems.

“If you’re walking down the sidewalk, you don't want to walk into a tree pit or have a wheelchair go into the tree pit,” said Nathan Randolph, a geographic information systems specialist for the city’s forestry division. “We’ve got to have enough width there for foot traffic.”

These limitations mean planters give preference to varieties less likely to take up a lot of sidewalk space in the future. And even planting those trees takes more work here, because it often means breaking concrete.

LEWIS SHARPE'S URBAN MIRACLE

Public health officials say urban neighborhoods can combat climate change by creating more green space. Lewis Sharpe, 81, has done that in Broadway East. Since 1988, he has operated an urban farm on a plot of land where vacant rowhouses once stood. It's called the Duncan Street Miracle Garden, and it now boasts rows of vegetables and fruit trees, which contribute to the neighborhood's tree canopy.

(Video by Maris Medina | University of Maryland)

Planting trees is only part of the canopy equation. Preserving the existing large trees that comprise the current canopy is just as critical. A mature tree can provide significantly more cooling power than a new one, as the 35-foot Callery pear tree in front of Mary Boyd’s rowhouse on East Lanvale Street in Broadway East demonstrates.

This tree — exemplary for Broadway East, average in Roland Park — has stood in front of Boyd’s house for the 50 years she’s lived here. It casts cooling shade and augments her window air conditioners on the hottest days.

“It’s lovely,” she said of the pear tree, which she waters sometimes. “It keeps the sun down.”

Mary Boyd has had a pear tree in front of her home for the 50 years she’s lived in the Broadway East neighborhood. But two other trees on her side of the block are due to be removed because they’re in poor health — a trend she’s witnessed over the years. “We miss ‘em, oh yes we do,’’ she says of the trees. (Photo by Maris Medina | University of Maryland)

There are two other trees on her side of the block, a pair of 35-foot red maples. The city graded them in poor condition and has identified the trees — and their thinning canopy — for removal.

Years ago, there were more trees on this street, she said, with canopy so dense “you couldn’t see up one side,” she said.

“We miss ‘em, oh yes we do,” she said. “But I thank God for what we do have.”

Her pear tree is in “fair” condition, according to the city. Unfortunately, the larger street trees in this neighborhood are simply less healthy than they are in cooler neighborhoods to the north.

Less than half of trees with a trunk larger than 6 inches in diameter were labeled “good” by the city’s most recent street tree census, compared to about 75% in Roland Park.

Planting trees and keeping them alive costs significant money. Baltimore’s urban forestry division budget has grown by 50% since 2012 to $4.4 million, more than the 30% growth rate in the city’s overall budget over the same period.

But the division has also faced cuts to key maintenance programs, most notably a $250,000 cut in “proactive pruning” and disease management programs aimed at keeping trees healthy in fiscal year 2019. Dihle called the proactive pruning program an “important component of the quantity and quality of our tree canopy.” The funding was transferred to support community recreation centers.

“Any department head or division chief worth his or her salt will tell you it's not enough, of course,” Dihle said of the city’s expenditures.

State Del. Robbyn Lewis, who represents parts of East Baltimore, questioned the city’s priorities in spending 100 times more on police than it does on trees.

“And you wonder why we have no trees,” she said.

The funding limitations mean nonprofit groups make up an important part of the tree planting and maintenance effort in Baltimore. Residents, too. Anyone who fills out a form to request the city plant a tree in front of their house must agree to water and provide care for the tree for two years.

Resident hostility presents a challenge in parts of the city, where some say they simply do not want trees. Just east of the Broadway East border, workers broke the concrete sidewalk to plant a maple tree in front of Karen Pailin’s rowhouse over her objections, she said.

“Mostly what I get in the city about trees is disinterest. Because there’s so many other pressing social concerns that the trees are not even almost on the radar.”

- Alex Smith, Baltimore Tree Trust

She had a laundry list of concerns, including the fact that it drops leaves in the fall.

“We didn’t ask for them. We didn’t vote for them. But they put them here anyway,” she said.

Others are excited about trees. For most of the 40 years Lorraine Diggs has lived in her row house on Monument Street, just to the southeast of Broadway East, it was fronted by bare sidewalk. When workers from the Baltimore Tree Trust came to her recently with a plan to break the concrete and plant a tree, she helped select the black gum that now grows there.

“I just wanted something that would stand out,” she said. “Because I’m a standout person.”

East Baltimore resident Lorraine Diggs encourages her neighbors to maintain the trees on the block. She dedicated the small garden in front of her house to her late mother. (Photo by Maris Medina | University of Maryland)

Diggs decorates her tree for major holidays, most recently wrapping them in red, white and silver garlands for the Fourth of July. Even in Baltimore’s hottest neighborhoods, that level of enthusiasm for trees is rare, said Smith, based on hundreds of conversations a year with residents.

“Mostly what I get in the city about trees is disinterest. Because there’s so many other pressing social concerns that the trees are not even almost on the radar,” he said.

Pressing social concerns like crime. Indeed, in Baltimore, the needs of the police department sometimes take precedence over the goal of growing the tree canopy, despite solid academic research showing the presence of trees can actually reduce crime.

“Trees, to the criminal, are … like a sign that says ‘neighborhood watch.’”

- Morgan Grove, a research forester with the U.S. Forest Service

Trees send a signal that a neighborhood is cared for by the people who live there, said Grove, who has studied the relationship between crime rates and tree canopy. Shady trees also help create “social cohesion” in neighborhoods, because people in areas with a lot of tree canopy are more likely to spend time outside and know their neighbors by name.

And, Grove said, “Trees, to the criminal, are … like a sign that says ‘neighborhood watch.’”

Since early 2018, trees were removed or trimmed back at least 94 times across the city at the request of the police department, records show, including one a few blocks south of Broadway East.

“The police department says, ‘Gee, we can't see down the street. This entire row of zelkova trees is in our way, can you whack them back or get rid of them, so we can look for the drug dealings going down at the liquor store at the corner down there?’” Dihle said. “We will push back.”

In some instances, Dihle said his division will trim the trees back instead of removing them to avoid “doing more harm than good.”

The Baltimore Police did not respond to several requests for comment.

In Broadway East, nearly a third of homes are vacant, the most prominent marker of disinvestment here. Across the neighborhood, indifference allowed trees to grow large in concrete alleys behind vacant houses.

Vacants prove fertile ground for tree growth

Between 2007 and 2015, the large concentration of vacant houses in Broadway East helped contribute to the growth of the neighborhood's tree canopy. Throughout the neighborhood, it's not uncommon to see trees growing into — and often through — vacant homes. Slide the bar to see how the tree canopy changed in this section of Broadway East that features entire blocks of vacant houses.

BY XANDER READY

Source: Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service analysis of tree canopy data via U.S. Forest Service and University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab; and vacancy data through July 2019 via City of Baltimore.

It’s not uncommon to see trees growing large through the shells of vacant homes, collapsed roofs allow nourishing light to intrude.

The city and state are moving to demolish vacant homes here, part of a citywide effort called Project C.O.R.E., to remove blight and make way for future developments and investment in this historically underserved neighborhood. All of that has implications for the existing tree canopy.

In late June, there were seven vacant rowhouses in the 1500 block of North Bradford Street in Broadway East. A few weeks later, they were gone, systematically “deconstructed” by workers from Details, a firm that specializes in removing salvageable materials — brick, wood, marble — from Baltimore’s neglected rowhouses before they are demolished.

As foreman Davon Jones and his crew arrived one steamy July morning, there were piles of red bricks nestled against one of three large trees Jones’ crew had carefully avoided taking down. They had to remove one tree behind the houses that showed evidence of extreme poor health that, in their judgment, was at risk of falling into electrical wires.

But, Jones said, “If you got trees growing inside the house, it has to come down.”

In the Broadway East neighborhood, it's not uncommon to see trees growing through the hollowed-out shells of vacant houses, like this one on East Oliver Street. (Drone footage by freelance videojournalist Nate Gregorio)

On a densely forested patch five blocks to the west, on North Washington Street, Dave Landymore was loading into a truck busted up concrete that once formed the foundations and parking pads of more than a dozen rowhouses. In the decades since they were demolished, dozens of trees, some of the largest in the neighborhood, had been allowed to grow.

Landymore’s organization, The 6th Branch, cleans up vacant lots in some of Baltimore’s hottest neighborhoods. They preserved most of the trees on this lot, but removed a few, to make it more accessible for people in the neighborhood.

“The only real benefit remaining to the neighborhood is the tree canopy,” Landymore said. “The goal is to make this a clean, inviting safe space for the neighborhood, while preserving environmental benefit.”

Jake Gluck and Jane Gerard of the University of Maryland contributed to this story. Meg Anderson and Nora Eckert of NPR also contributed to this story.