CHAMP, Md. — Eric Bedsworth’s day of reckoning arrived a year ago.

His soybean field got such a salty soaking from last fall’s tidal waters that he abandoned it mid-harvest. This season, the land sprouts only weeds. Unless researchers create a salt-tolerant crop to his liking, Bedsworth likely never will plant this soggy field again.

“I hate to see the land go out of production. But I’ve lost so much money down there,” said Bedsworth, a third-generation farmer in Somerset County, Maryland.

His is a fate farmers increasingly confront amid rising seas and punishing storms, according to a study by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland.

Thousands of acres have been abandoned on the Eastern Shore peninsula that lies between the ocean and Chesapeake Bay, spanning three states. The long-farmed land was “the breadbasket of the revolution.”

Nearby, Bob Fitzgerald also took a field out of production.

“I quit farming it because it drowned out every damned year,” said Fitzgerald, 81, whose family has farmed in Somerset County since the mid-17th Century.

Surveying a salt-scarred patch in another field, he summed up the plight of many farmers: “It’s an issue that’s here and going to stay and we’re going to have to live with it.”

With seas rising, farmers along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts increasingly suffer from one of the initial impacts of climate change: saltwater intrusion. The plague of salt is arriving not just from storms and tide but also underground, where it can migrate undetected until crops shrivel. Often, the damage is compounded by farming methods ingrained over the years.

In North Carolina, rich coastal lands drained for farming are going barren as saltwater soaks into the earth and advances inland through drainage ditches dug for the opposite purpose: to carry water away.

In Florida, rich farmland of the past has turned to marsh, and in recent years storms and salty tides rob acreage of productivity miles inland.

One of the world’s most productive farmlands, California’s Central Valley, lies partly atop an ancient salt sea, a geologic history that already had left salty soils. Growers get irrigation water with salinity pumped from the California Delta, a transition zone between saltwater and freshwater. An estimated 250,000 acres have gone out of production due to salt accumulation and 1.5 million acres are designated salt-impaired.

“It’s like the early stages of cancer,” said Daniel Cozad, executive director of the Central Valley Salinity Coalition, an alliance of public agencies, nonprofits and private interests.

“You don’t feel it, you don’t see it and everything seems to be pretty normal. But if you’re not keeping track of it, it can get much worse,” he said.

‘Even weeds won’t grow’

In Maryland, soils that nourished corn, soybeans and vegetables on the Eastern Shore are overrun with phragmites, jungles of sharp-leaved invasive plants 10 feet or more in height.

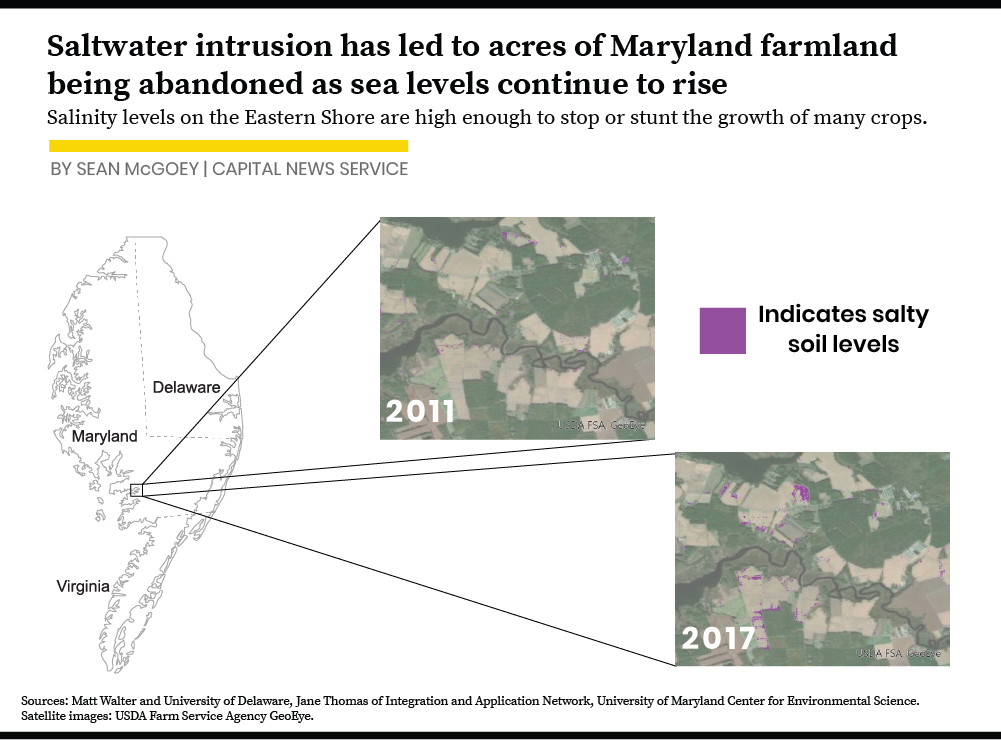

Soil testing by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland showed levels of salinity too high for common crops. A dozen samples on field locations showed salinity levels ranging from 1.3 parts per thousand (ppt) to 3.6 ppt — enough to stop or stunt the growth of traditional crops.

Fifty miles north in Dorchester County, Maryland, samples from a cornfield of shriveled stalks showed salinity ranging from 3.7 to 4.5 ppt. Corn seedlings typically don’t withstand more than 0.9 ppt.

“I don’t think even weeds will grow in some places,” remarked the property owner, Richard Abend.

Change has arrived more swiftly in the mid-Atlantic than along other coasts because land is sinking, a geologic process begun millennia ago after advancing ice raised its level. It continues to subside, a factor in seas rising from 3 to 6 millimeters a year, depending on location, hastening research to help farmers and landowners adapt.

In September, the National Science Foundation awarded a $4.3 million grant to University of Maryland agroecologist Kate Tully and colleagues in Delaware and Virginia to study the transforming effects on the already watery coastal lands of Delaware, Maryland and Virginia — the Delmarva Peninsula.

The award could yield benefits beyond the Atlantic coast. A United Nations University study six years ago estimated nearly 5,000 acres of land was being lost daily from salt degradation — 62 million hectares (153 million acres) affected already. The study noted salt-degraded lands in Central Asia, the Yellow River Basin in China, the Indo-Gangetic Basin in India, Pakistan’s Indus Basin, the Euphrates Basin in Syria and Iraq, the Murray-Darling Basin in Australia and the San Joaquin Valley in California.

In Maryland, the U.S. Department of Agriculture found a drop in farm acreage of 9% in between 2012 and 2017 in Somerset County, a place whose population also has declined below its 1900 Census tally.

Somerset’s loss of uplands over eight years was nearing 2.4 square miles, most of it farmlands, according to newly published research by wetlands ecologist Keryn Gedan of George Washington University, and Rebecca Epanchin-Niell, of Resources for the Future, members of Tully’s research team.

Tully and colleagues are seeking crops that can tolerate salt even as she and other researchers unravel the complex changes in soil chemistry as salt creeps farther inland. The salty and wet conditions can trigger release of phosphorus and nitrogen stored in fields from farming, polluting the surface and groundwater.

Tully’s team monitored Somerset County’s waters for three years before publishing research documenting that nutrients that have accumulated on farm fields “are moving downstream through connected agricultural ditches and tidal creeks.”

That exodus could mean more trouble for Chesapeake Bay, where dead zones of oxygen-starved waters — caused in part by fertilizers — nearly tripled last year.

Corn to Quinoa?

In 1988, farmers and pundits slapped their knees over Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis’ suggestion that Belgian endive replace corn and soybeans in rural Iowa. The vision of tiny white heads sweeping to the horizon was strange enough. More improbable was finding a market in rural Iowa for vast quantities of an expensive lettuce with a foreign name.

Alternative crops are taken more seriously today. If, that is, “a farmer has the right expertise to grow and make a profitable harvest,” said Paul Ulanch, executive director of North Carolina Biotechnology Center’s crop commercialization program.

Andrea Gibbs of the North Carolina State Cooperative Extension service for Hyde and Tyrrell counties tested kale, asparagus and beets in the coastal region called “the Blacklands” in tribute to its historic fertility.

In 2016, the region was pummeled by slow-draining saltwater from Hurricane Matthew, the first Category 5 storm in the Atlantic in nine years. Two years later, Hurricane Florence hit, leaving behind the wettest Carolinas on record.

Add in the gradual salting from rising seas and more frequent tides, and parts of this land no longer welcome traditional crops. Asparagus, on the other hand, did fine, Gibbs said.

But as was the case with Belgian endive in Iowa, it’s doubtful that sufficient markets could be found in rural North Carolina for tons of asparagus.

In California’s Central Valley, some farmers have turned to Jose tall wheatgrass, animal fodder that can withstand heavy salting.

“Sounds like it’s a great idea, except almonds are worth a lot more than Jose wheatgrass,” observed Cozad, the Central Valley Salinity Coalition director.

In southern Maryland, Tully has experimented with crops that have more promising markets than asparagus. Sorghum might be used to feed chickens in Eastern Shore broiler houses. Switchgrass has potential as poultry bedding. Barley, which she said fared “pretty good” in her test plantings, could be sold to regional microbreweries.

Quinoa, a super grain and technically a fruit, is among the most salt-tolerant food crops. But farmers outside Colorado have shown little interest.

Tully has tested soybeans bred to withstand salt but reports little success, not good news along Maryland’s lower Eastern Shore, where farmers in three counties planted about 85,000 acres of soybeans last year.

At Cape May Plant Materials Center, a U.S. Department of Agriculture installation working on problems in nine states, a dozen of the 16 crops being tested aim at adaptation to salty soils, according to Christopher Miller, installation manager.

Miller noted the potential for alternative crops of saltmeadow cordgrass for mulch or hay to feed animals, adding, “If the markets are there. Now that’s a whole other issue.”

‘Running out of time’

The USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service is signing up farmers willing to turn over salt-scarred land for restoring marshlands and other conservation purposes.

From aerial photos, The Nature Conservancy identified dozens of parcels in Maryland and Virginia where salt buildup was so heavy along farmland ditches that they looked like roads from the air.

Appeals to landowners showed some recent success. In Maryland this spring, the conservancy said it had agreements to put 130 acres into permanent preservation.

Projects in Virginia show promise. Near Bloxom, a tiny town along the Chesapeake Bay, the Natural Resources Conservation Service has begun an elaborate wetlands restoration project on 33 acres surrounding a home built in 1730.

The agency planted millions of seeds of plants with names that suggest they are up to the task of battling saltwater, creeping spikerush and bearded beggarticks among them.

Dr. Charles Wilder, who owns the land, is keenly aware of the climate crisis and signed up for the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program because, he said, he wanted to put his acreage to good use.

“I think we’re running out of time, I really do,” said Wilder, 67.

Near the town of Accomac, Virginia, close to the Atlantic Ocean, a farmer weary of ruined crops signed up for the Conservation Stewardship Program, which includes rental payments and Natural Resources Conservation Service expertise.

In July, a field barren and salt-scarred a year ago shone the brilliant yellow of Plains Coreopsis.

Coreopsis is one of nine salt-tolerant plants that bloom successively. “A smorgasbord for native pollinators,” is how Jane Corson-Lassiter, district conservationist at the USDA’s NRCS, described the lush meadows buzzing with bees.

“I think there’s going to be a lot of interest for these salt-intruded sites,” she said.

Getting to the point where landowners agree to subscribe to programs and easements — the legal right to use part of their land — is challenging work. They might see more value in priming the land for duck hunting, a Delmarva tradition that would bring in some income.

“Most landowners really don’t want to change things unless they can see a clear benefit for themselves,” said Jim McGowan, The Nature Conservancy’s regional land protection manager in Virginia. “They don’t want to see land taken out of production unless it’s gotten to the point where it’s so wet that it’s not worth their time.”

That time is fast coming. But environment-friendly escape routes for farmers likely will narrow, along with other state and local attention to coastal defenses, as a result of pandemic-squeezed state and local budgets.

“We won’t see any programs like that in my lifetime,” said Larry Fykes, 66, the Maryland Department of Agriculture’s soil conservation district manager in Somerset County, referring to financial assistance for farmers planting trees. “COVID-19 has hit everything.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.