On Louisiana’s Gulf coast, hit by a record five hurricanes or tropical storms this year, Native American tribes are some of North America’s early climate refugees as seas claim their shoreline and salinity damages the land that remains.

Four Louisiana tribes requested United Nations assistance this year to force action by the U.S. government. They wrote in a formal complaint citing “climate-forced displacement” that saltwater has poisoned their land, their crops and their medicinal plants.

“That strips us of not only being able to generate an income to provide for ourselves, it also strips us of our ability to feed ourselves healthy,” Shirell Parfait-Dardar, chief of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, said in an interview.

The tribes’ plight offers an extreme example of a lesser-known impact in the climate crisis: saltwater intrusion.

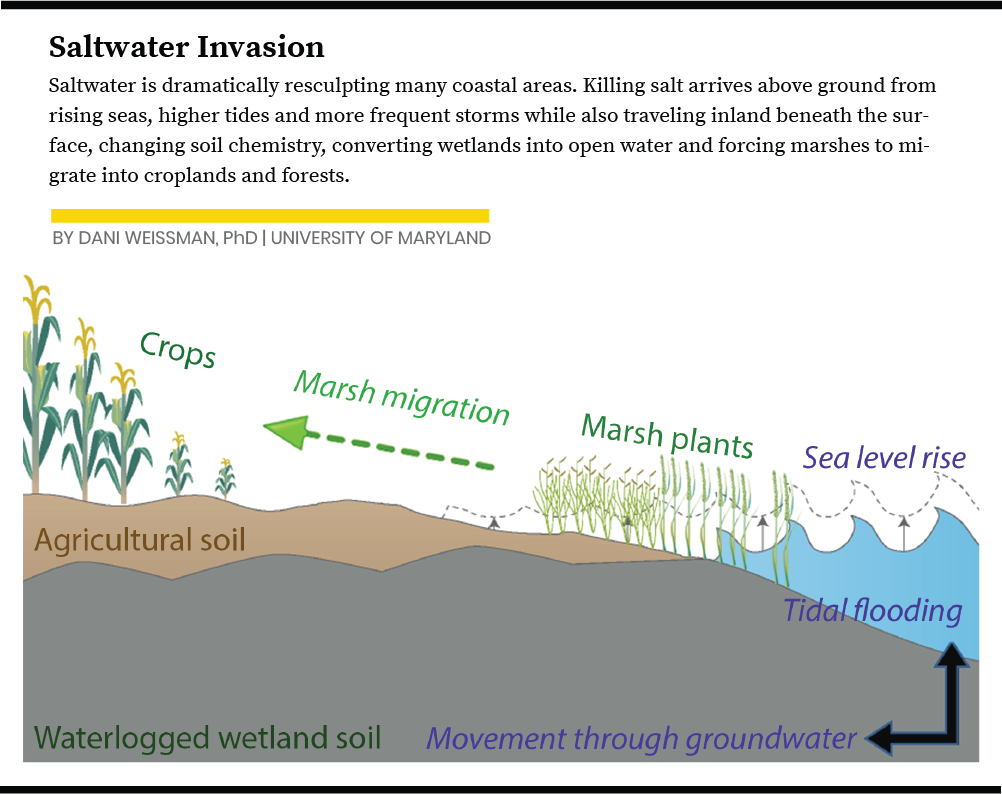

The landward movement of seawater threatens drinking water supplies, coastal farming and coastal ecosystems.

The cascading consequences of saltwater intrusion were starkly revealed in interviews with more than 100 researchers, planners and coastal residents, along with soil testing and analyses of well-sample data conducted by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism.

New scientific research shows measurable and sometimes startling change, much of it from saltwater’s unseen advance beneath the surface. The threat is widespread; roughly 40% of Americans live in coastal counties, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Rising seas, more frequent storms, higher tides, drought and the pressure of pumping for drinking water combine to accelerate the salt invasion. Researchers say that as effects of the changing climate worsen, challenges for landowners, local planners and people concerned about sensitive coastal lands will grow.

“It’s not something that we need to wait until 2050 or 2100 for. It’s not something happening only to polar bears. It’s happening right now,” said Marcelo Ardon, a North Carolina State University ecologist and biogeochemistry who is documenting changes in North Carolina’s coastline. His view of the impact of saltwater intrusion is widely held in scientific circles.

Among the Howard Center’s findings:

• Thousands of acres of farmland have gone out of production as salt imparts its ruinous properties to croplands. In southern Maryland, Howard Center soil testing showed salinity well above levels that stunt the growth of crops or prohibit them altogether.

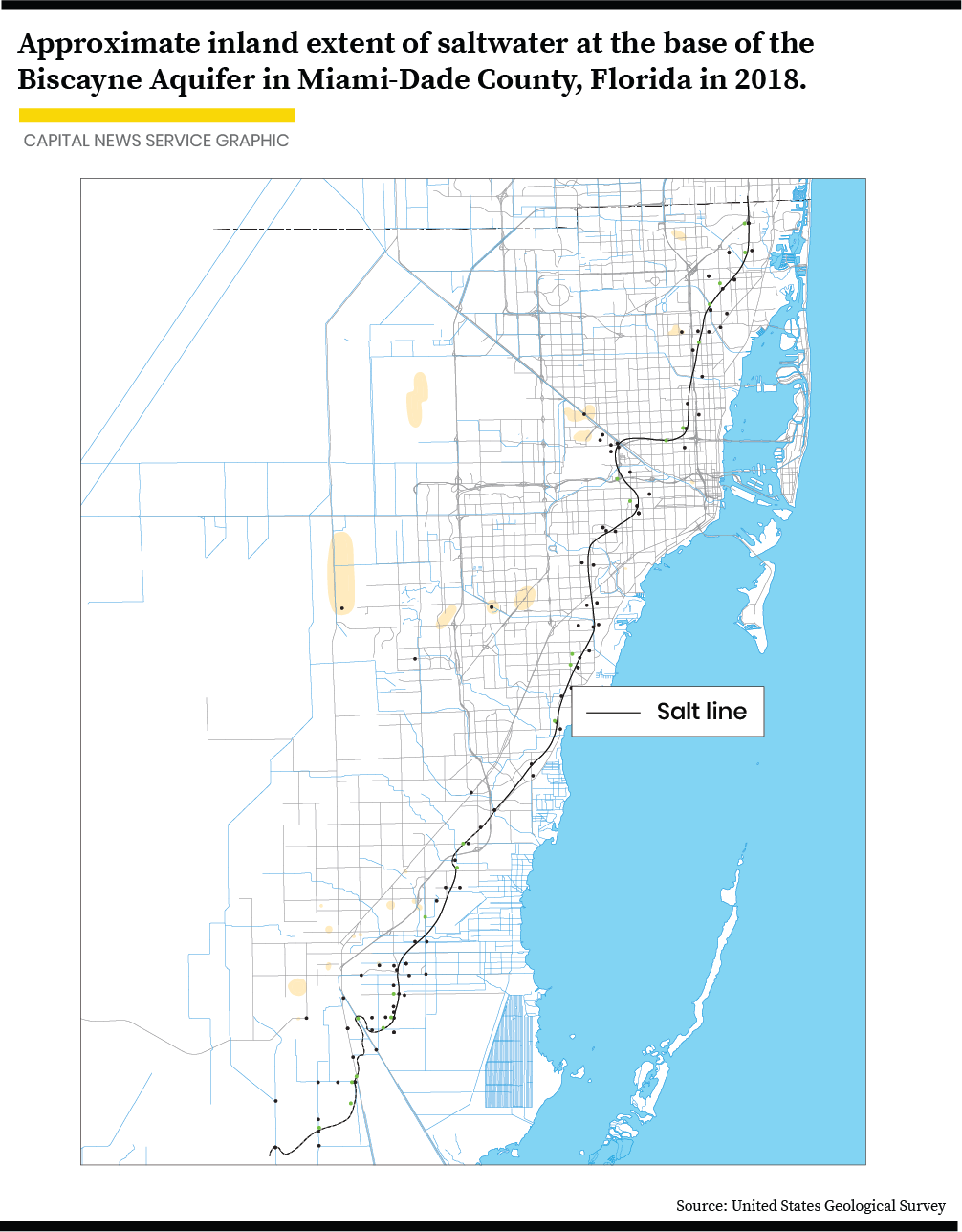

• Drinking water supplies in public aquifers and private wells are increasingly threatened, with utilities in coastal areas closely monitoring salinity and routinely seeking new water sources. Advancing saltwater, several hundred feet yearly in some areas, translates to higher water bills for homes and business.

• “Ghost forests” of dead and dying trees are spreading along coastlines from New Jersey to the Gulf of Mexico as saltwater pummels from above and seeps in from beneath. Once-verdant coastlines along the Chesapeake Bay are being transformed into foreboding vistas of bleached-white tree skeletons engulfed by invasive plants.

• Coastal wetlands, a buffer against more frequent storms and a sink to capture carbon, are fast disappearing. Refuge managers and conservationists are hastening efforts to find new corridors for marshes to migrate to preserve benefits for people and wildlife.

In one recent success, Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge in southern Maryland — a focus of researchers from around the world because of its rapid change — acquired over 3,000 acres for marsh migration.

The transaction pointed to the stakes as coastal lands rich in history disappear: Ten acres of a newly purchased parcel was the homestead of Ben Ross, father of Harriet Tubman, the abolitionist and underground railroad conductor who led the pre-Civil War escape of dozens of slaves.

The Invisible Flood

In early Japanese theater, salt was sprinkled on stage to ward off evil spirits. In Haitian voodoo, salt is a means to purify and bring zombies back to their senses. Now, salt is bedeviling coastlines as its complex and damaging effects become known.

“It’s an enormous change, immense,” Emily Bernhardt, a Duke University ecosystem ecologist, said of saltwater’s impacts. “Even as an expert on the topic, I have been shocked to discover the extent of coastal forests lost to sea-level rise and saltwater intrusion over the last several decades.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the United Nations scientific body established to study the warming climate and prepare for change, observed in a report last year that information is lacking.

“Protection-based adaptation to saltwater intrusion is more complex than adaptation to flooding and erosion, and there is less experience to draw on,” the panel wrote in its special report on oceans.

University of Maryland agroecologist Kate Tully is leading a regional team in search of saltwater-tolerant crops. She described complex changes from salt as “The Biogeochemical Olympics” while speaking to a Princess Anne, Maryland, audience earlier this year.

In July, the National Science Foundation awarded Tully and her partners a $4.3 million grant to study saltwater intrusion — a measure of scientific concern about the problem.

The five-year grant seeks a better understanding of how coastal lands are being transformed to help landowners, farmers and environmental planners cope with sea-level rise and more frequent inundations from high tides and coastal storms.

Tully is in the midst of a separate study along Maryland’s Eastern Shore under a U.S. Department of Agriculture grant. Along with her partners from the Harry R. Hughes Center for Agro-Ecology, she received yet another grant this fall, $470,000 from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. The award aims to restore wetlands and devise strategies to adapt to salting lands.

One of Tully’s research partners, Matt Kirwan, of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, will use the National Science Foundation grant to attempt to measure how the elevation of lands changes when farmlands are turned to marsh.

Land along the mid-Atlantic coast already is sinking as a result of geological processes begun in the last ice age. Kirwan’s research could show whether the subsidence is accelerating under recent inundation, potentially important because it could mean the effects of climate change will be even more severe than predicted.

Duke’s Bernhardt said research in the next few years will be critical to assist coastal communities suffering declining revenues and budget woes from the pandemic.

“These salty fields and dying forests are happening throughout rural coastal areas, which are often economically disadvantaged,” Bernhardt said. “I worry about whether farmers and landowners in these communities will have the resources needed to adapt to the changes already occurring. We’re putting a lot of money into planting things that will not survive in a saltier, wetter future. We could be more creative.”

Tully has emerged as a spokeswoman as the reality of encroaching salinity sets in. In a TEDx talk she delivered in Great Mills, Maryland, in September, she said: “Many people are unaware, but there is an invisible flood moving far inland in advance of the surface floods that can drown our homes.”

She added in an interview: “We can’t in the short term stop the seas from rising, but we can manage this transition intelligently and do it in a coordinated way. But we have to have buy-in from farmers, from the communities and from local governments. And the solutions need to be science-based.”

‘Sleeping giant’

People in some of the world’s deltas badly need solutions.

After upstream dams in China altered the flow of the Mekong River, Vietnam People’s Navy ships stepped in this year to transport freshwater to the Mekong Delta as salinity pushed as far as 60 kilometers inland. The United Nations, along with Vietnamese artists and performers, contributed cash to help victims survive the salt crisis in the country’s “rice basket.”

In Bangladesh, rising seas from the Bay of Bengal further inundated the lower delta plain, poisoning crops and grazing land. A research paper published last year concluded that 20 million Bangladeshi people were at risk of hypertension from saltier drinking water. A study monitoring women’s health nearly a decade ago blamed miscarriages on saltiness of waters.

Saltwater intrusion also is a threat to lands inland.

“It’s the sleeping giant of most semiarid regions on the planet,” Wesley Danskin, a research hydrologist at the U.S. Geological Survey in California, said of troubles stemming from salt.

Danskin described chloride showing up increasingly in California wells as “probably worse than any other contamination.”

In California, where salt is a significant threat in the farm-rich Central Valley, local agencies are implementing plans to balance overdrafted aquifers — critical water supplies that are prone to saltwater intrusion.

Marc Del Piero, an expert in water law who once sat on the state’s Water Resources Control Board, remarked that growing crops in salty soil is “like trying to make a pair of shoes without any leather.”

“If those aquifers are not recharged and restored, eventually you won’t have any agriculture,” he said. “That’s the issue here.”

Proponents say recharging aquifers by putting freshwater back into them will preserve agriculture in California, which produces the vast majority of artichokes, almonds, olives, kiwi, plums and pistachios eaten in the United States. But the path to sustainable agriculture is laden with sacrifice.

Over the next 20 years, farmers in California may have to fallow anywhere from 500,000 to 1 million acres of farmland due to a decreased water supply, according to estimates by the Public Policy Institute of California. More than 10,000 people in the industry could lose their jobs, and billions of dollars in annual revenue on crops and related activities.

Thousands of acres of farmland already have been lost due to increasing salinity, and a University of Vermont study published this year found that most farmers believe California groundwater regulation is necessary, despite the sacrifices.

Areas ‘removed from the rest of the world’

Disappearing wetlands is increasingly a problem around the world. A study published in October in Earth-Science Reviews concluded that drought, which prohibits freshwater recharge of wetlands, is a significant threat that can be “difficult to determine before an event but which poses a catastrophic risk.”

The U.S. Geological Survey is working with nations around the world. The agency’s Wetland and Aquatic Research Center has partnerships with a Chinese government agency and a Chinese university in addition to projects in Singapore, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands.

Researchers in Australia will soon be conducting some of the same studies done in the southeastern United States under another new partnership.

Both for environmental and economic reasons, many nations want to better understand the capacity of wetlands to store carbon.

Coastal wetlands and mangroves increasingly inundated by saltwater are some of the world’s most effective carbon-storage ecosystems. They capture carbon dioxide — the primary greenhouse gas from human activities — and permanently store it, preventing it from entering the atmosphere.

Although no carbon-trading system has yet emerged under the Paris Agreement, many nations are looking ahead to the time of a functioning global carbon market that enables countries and corporations to meet emission-reduction goals by buying credits that, in effect, invest in carbon-cutting projects elsewhere.

U.S. Geological Survey research ecologist Ken Krauss is working with foreign partners in documenting what happens in the transition from marsh to forested wetlands.

“It’s a system that has the potential to be managed,” he said. “Over time, if we can figure out how to do it, you can manage these forests to make them more or less tidal to potentially sequester more carbon and store it long term.”

In the University of Virginia’s Plant Ecology and Remote Sensing Lab, Elliott White Jr. deploys satellite imagery to compute ongoing losses of fragile coastal lands. From National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration satellite data, he calculated that coastal regions from Maine to Texas had experienced a net loss of 5,387 square miles of coastal and river swamps in a 20-year period from 1996 to 2016.

White wrote part of his doctoral dissertation on how saltwater stunts the growth of freshwater trees in coastal forests. With saltwater advancing through rivers and groundwater, forests inland will experience similar loss in diversity and loss in size, he said.

Invading saltwater kills trees from the roots up, leaving ghost forests like this one in the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. (Willey’s Drone Service/Cambridge, Md.)

There are many reasons to care about the fate of swampy coastal lands, he said: “Swamps, despite people always wanting to drain them, are important for cultural reasons. People should care because if we lose these wetlands, we’re losing a multitude of things.’’

Throughout history, coastal swamps have offered refuge for people in need of it, among them enslaved people and Native American tribes. Cajun culture sprouted where the Acadians settled in the swamps of southern Louisiana. Even Shrek, the fictional ogre, lived in a swamp.

“I think of these natural areas, particularly marshes and swamps, as places people have retreated to in times of crisis, in times of change,” said Kirwan, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science researcher.

In the pandemic, people have been drawn to refuges in the tidewater areas. From March through June this year, Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge in Maryland reported visitor increases ranging from 56% to 412%, despite a shuttered visitors center due to the coronavirus. It reopened Oct. 2.

In July, the state of Virginia closed the Cape Charles Natural Area Preserve, citing too much pressure on fragile lands caused by “the urge to get outside during the pandemic.”

David Kaplan, who heads the H.T. Odum Center for Wetlands at the University of Florida, offered a personal assessment of a swamp’s allure as a getaway: “Stand in the shade of a quiet swamp with 100-year-old cypress trees towering above you, with the birds and wildlife, and you think about the majesty and the grandeur of a place that is removed from the rest of the world.”

As forests give way to marshland and open water due to invading saltwater, snow geese and other waterfowl get new habitat. Their visits this summer drew thousands of visitors to wildlife refuges along the coast. (Bill Lambrecht/University of Maryland)

‘Heartbreaking to watch’

The Louisiana coast lost the equivalent of a football field of land — 100 yards — every 100 minutes from 2010 to 2016, the U.S. Geological Survey reported three years ago.

A team that delved back 8,500 years by taking core samples of the Mississippi Delta predicted this spring that seas likely could swallow remaining wetlands in 50 years — or it could take longer.

The changing climate is one cause. In addition, in order to operate their boats, drilling rigs, pipelines, and other heavy machinery in Louisiana and other Gulf states, oil and gas companies have cut tens of thousands of miles of canals through delicate wetlands, enabling faster inland flow of saltwater.

Along the Louisiana coast, the tribes threatened with relocation have yet to hear an answer from the United Nations on their request to two special rapporteurs, one on the rights of internally displaced peoples and one on the rights of Indigenous peoples.

Special rapporteurs are appointed by the U.N. Human Rights Council to investigate human-rights violations and publicly report their findings.

“The communities who have done the least to cause the increase in greenhouse-gas emissions are on the frontlines of addressing this awful issue,” said Robin Bronen, executive director of the Alaska Institute for Justice, which has guided the four Louisiana tribes and an Alaska Native tribe in the legal process.

In their complaint against the United States, the tribes are seeking to protect their right to self-determination and assurance that they would play a significant role if and when relocation becomes necessary. They also want government funding to help restore their land.

On Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw land, Chief Parfait-Dardar said saltwater has killed trees, which leads to more erosion, while destroying community gardens.

“We have plants that would treat anything … good, pure medicines that worked,” she said.

Saltwater intrusion, she said, “affects everything. … It’s all working in one big circle and it’s quite heartbreaking to watch.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.