Deep beneath the Homestead-Miami Speedway, home of NASCAR’s Dixie Vodka 400, saltwater carries on a slower but more consequential race into the drinking-water supply of 3 million people in South Florida.

In 1999, the U.S. Geological Survey installed one of its first monitoring wells there using an electromagnetic technique to measure the thickness of intruding saltwater into the Biscayne aquifer. The racetrack is situated 5 miles from the Atlantic Ocean.

By 2018, a saltwater wedge at the bottom of the aquifer had expanded to a thickness of 20 feet. By last year, the chloride concentration had increased more than tenfold, to 12,000 milligrams per liter. The chloride concentration of seawater is about 35,000 milligrams per liter.

South Florida’s flooding streets get the attention, but what is happening beneath the surface presents clear — and in some cases eye-popping — evidence of another threat: saltwater intrusion.

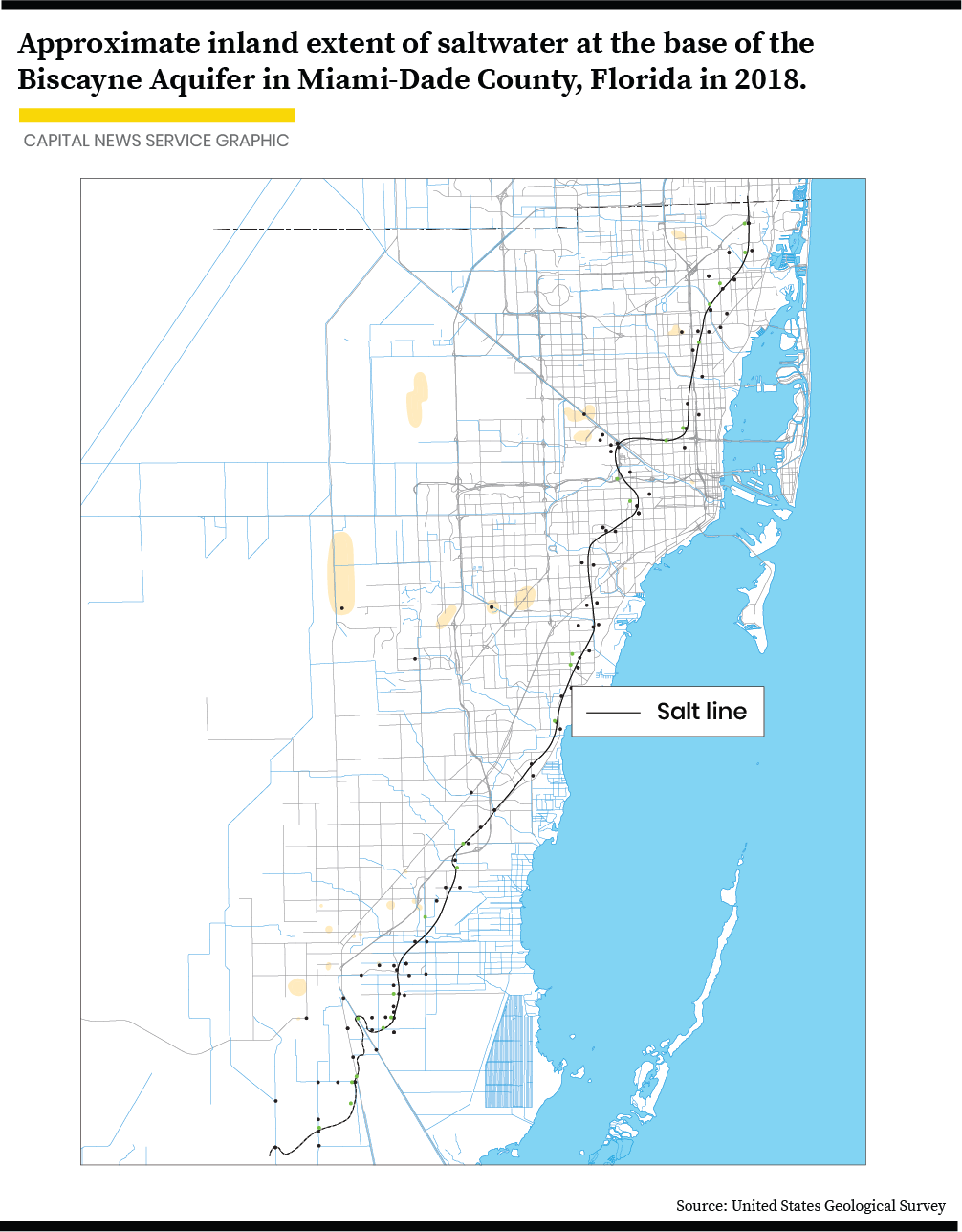

Analysis of chloride testing in South Florida by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland shows dozens of instances where the point at which saltwater meets freshwater — known as the interface — is moving inland.

U.S. Geological Survey testing shows saltwater has continued to migrate into South Florida’s aquifer system. Nearly one-third of 215 monitoring wells showed a five-year trend of increasing salinity with just 16 showing a downward salinity trend. (Test results at many other wells also showed increasing chloride levels, but those were not viewed by government hydrologists as a significant trend.)

The Geological Survey began special monitoring in Florida in the 1940s when wells too salty for drinking became common. Records since reflect a relentless salting of South Florida, a threat both to drinking water and to the environment.

Federal and state agencies have been monitoring sea-level rise for decades. Yet the Nuclear Regulatory Commission did not consider the impact of rising seas and increasing salt before granting a first-ever, 80-year license in December for the Turkey Point nuclear plant on Biscayne Bay. The plant is cooled by a series of canals that spewed millions of gallons of heavily saline water into the aquifer beneath it.

In a case playing out in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia challenging the relicensing, environmental advocates contend the NRC didn’t adequately consider the plant’s pollution and future impacts of climate change.

Above ground, more extreme storm surges and high tides also deliver salt, sometimes far inland. By 2050, destructive high tides could plague the southeast Atlantic by anywhere from 25 to 85 days a year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts.

In July, the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact projected that by 2040, seas would rise between 10 to 17 inches over 2000 levels, based on predictions from NOAA and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the United Nations body that has studied the issue since the 1980s.

Harold Wanless, a University of Miami geographer known for sobering but accurate predictions about the changing climate, said the Atlantic Ocean in South Florida already is a foot higher than in 1930 and noted that saltwater advances inland from both the east and southwest.

“There’s major saltwater intrusion that is further diminishing our freshwater resources. And we’re probably going to lose most of (the freshwater resources) with another 2 feet of sea-level rise,” he said.

Wanless’ research at Cape Sable at the bottom of the Florida Everglades 15 years ago documented the environmental changes spreading across sensitive lands. His report to the U.S. Department of the Interior described Cape Sable as the canary in the coal mine, and recommended the government consider the safety of people using the back country there due to threats from widening creeks and higher waters.

Today, the National Park Service says of this once-pristine area: “The interior freshwater marsh has disappeared almost entirely.”

Adds Wanless: “We’ve lost almost all of the sawgrass marsh in Cape Sable because of saltwater intrusion.”

Disrupting a balance

Months after Florida became a state in 1845, the state Senate passed a resolution asking Washington to look into draining the vast, interconnected lands of freshwater that stretched from what is now Orlando to the Florida Keys.

By the start of the 20th Century, Florida politicians and their backers proceeded with fervor to reclaim the wild lands. Canals emptied Everglades water to pave the way for farming and development, part of the storied Florida land boom. The effects of upsetting the balance between freshwater and saltwater in low-lying Florida became apparent within decades as Miami-area wells grew too salty for use.

By 1940, the Geological Survey was monitoring dozens of wells to gauge saltwater movement. Government hydrologists concluded saltwater had already traveled miles into the Biscayne aquifer.

The Geological Survey has more than 100 monitoring wells from Jupiter to near the bottom of the Florida mainland, most of them 2-inch-wide PVC pipes that reach to the bottom of aquifers. Government hydrologists attempt to place the wells ahead of the saltwater to measure its pathways and speed as an aid to planners.

The movement can be dramatic, according to results examined by the Howard Center. A well in south Miami showed a modest chloride level of 24 milligrams per liter more than a half-century ago. The latest reading, in September, showed 5,650 milligrams per liter.

Last December, a Geological Survey well in southwest Miami along the Blackwater Canal suddenly showed a spike in chloride, to 600 milligrams per liter. The reading caught the eye of hydrologists because it showed how canals are enabling saltwater to flow farther inland even as it travels underground.

Scott Prinos, a hydrologist in the Geological Survey’s Caribbean-Florida Water Science Center, said most of the wells east of the saltwater front show the front continuing to move inland.

In July 2018, a newly installed well measured chloride at 302 milligrams per liter. In May, 22 months later, that saltiness had spiked to 2,100 milligrams per liter. In September, the chloride content was even greater — 2,310, well testing shows.

The well is situated 5 miles west of Florida Power & Light’s Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Station, where operations are proving to be yet another problem in South Florida’s quest to stave off a saltwater invasion.

Trouble at Turkey Point

A grand jury convened by the Miami-Dade County state’s attorney last year on the health of Biscayne raised alarms about saltwater intrusion driven by the plant. In Miami, grand juries venture beyond criminal matters into issues of public importance.

A massive plume of saltwater released by the plant’s unique method of cooling two nuclear reactors “constitutes a serious threat to the source of our freshwater,” the grand jury reported.

The nuclear plant has spewed millions of gallons of water, some of it saltier than the ocean, into the Biscayne aquifer and surrounding environment.

Florida Power & Light’s Turkey Point plant is 35 miles south of Miami between Biscayne National Park, an underwater marine preserve, and Everglades National Park. Florida Power & Light is a subsidiary of NextEra Energy Inc., which also has nuclear plants in New Hampshire, Iowa and Wisconsin.

Most nuclear plants deal with intense heat from reactors using cooling towers that dissipate the heat 300 feet and higher into the air. Since it began operating in the 1970s, Turkey Point has deployed a system of cooling canals 2 miles wide and 5 miles long that works as a heat sink.

Turkey Point’s 39 canals function as a massive radiator, cooling the water but leaving behind saltier, heavier water that migrates downward through porous limestone into groundwater.

In 2016, Florida Power & Light entered into a consent order with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection aimed at halting the inland movement of hypersaline water and retracting the plume in a decade’s time.

Two years ago, the company set in motion a two-pronged remedy: “freshening” canals by diluting them daily with more than 15 million gallons of low-salinity water while pumping higher-salinity water from the aquifer into recovery wells on the canals’ western edge.

Florida Power & Light claims success. In July, it reported to the state it had removed 8.4 billion pounds of salt from the Biscayne aquifer and begun reducing hypersaline groundwater west and north of the plant.

But the company also acknowledged it would miss a key goal — reducing salinity in its miles of cooling canals to the level spelled out in the consent order. The company would take further actions, including seeking permission to use more water to dilute canal saltiness.

NextEra Energy spokesman Peter Robbins said a lack of rainfall led to the shortcoming and the company had made “significant progress.”

Kirk Martin, a hydrogeologist who has worked for more than a dozen Florida cities and counties, said Florida Power & Light’s current remediation effort “is having no measurable effect on the deepest parts of the aquifer, where most of the hypersalinity is located.”

He added in an email: “And nor is it having an apparent effect on the westward migration of the saltwater interface.”

William Nuttle, an engineer and consultant on Florida water for two decades, was among the first hydrologists contracted by federal agencies to study what climate change has done and will do to South Florida. He has worked for the Department of the Interior, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and many others. He is now part of a team of water experts and lawyers representing the Florida Keys Aqueduct Authority in a state administrative hearing focused on the nuclear plant.

“They did their calculations and then did just enough. I don’t think they’re serious,” Nuttle said, referring to the cooling canals. “If I’m the engineer, I’m going to design it with some excess capacity so that I know there’s an ability to overcome unknowns. FP&L didn’t do that.”

Robbins said NextEra “has owned” the problem. “We have put a system in to address it. We have made a lot of progress with a lot of progress to make. On track, is the way I would describe it,” he said.

Paying more to drink

As director of Water and Sewer for Miami-Dade County, Kevin Lynskey has the task of assuring Miami-area residents have water to drink. The system is safe, at least through 2040 and likely beyond, he said, even though people and businesses will be paying more — 5% more for water and sewer every year at least through the next decade.

“Where we’re in trouble is with saltwater intrusion in the south, which moves a couple hundred feet a year,” he said. “As managers, we’re paying attention to that and we’re suggesting more investments along the salt front.”

He is seeking solutions for the troubled area, including storing excess water from the wet season in an aquifer and recovering it later to add to the canal system to help fend off saltwater. He’s also exploring methods of saving water used for agriculture that ends up lost to the tide.

“By the time our well fields are in trouble, the whole community is going to have much more significant problems” related to rising seas, he said.

You must be logged in to post a comment.