Sandra Kunz had been worried for her safety while working as a cashier at the Walmart in Aurora, Colorado, during the pandemic, her sister, Paula Spellman, said.

The 72-year-old had lung disease, Spellman said. She was “feeling uncomfortable because so many people (were) coming in with coughs.”

But Kunz didn’t complain to the government agency tasked with protecting workers, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, her sister said.

“Sandy’s not a complainer,” Spellman said. “She went out and just purchased her own mask and her own gloves.”

It wasn’t enough. On April 20, 2020, Kunz died from COVID-19 following an outbreak linked to the Aurora Walmart. At least 18 employees got sick and one other worker at Walmart, Lupe Aguilar, died.

Spellman said her sister fell ill first, then Kunz’s husband, Gustavous. They died from COVID-19 within two days of each other.

“She worked for them a very long time,” Spellman said. “They didn’t really care.”

Sales at Walmart, the world’s largest retailer, soared as Americans hunkered down during the pandemic. The essential workers serving them paid the price.

The Walmart where Kunz worked was one of at least 151 Walmart facilities in 10 states with available data where multiple COVID-19 illnesses were recorded, a reporting consortium led by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland found. That’s one quarter of the company’s stores and distribution centers in those states.

Walmart, the nation’s largest private employer, provides a window into OSHA’s performance during the pandemic. Many of the retailer’s nearly 1.6 million U.S. workers are vulnerable to COVID-19 due to income disparities, racial discrimination or language barriers. They depend on OSHA to guarantee safe and healthy workplaces.

The Howard Center’s collaboration with journalists from Boston University, the University of Arkansas and Stanford University found that the worker safety system is fragmented.

Responsibility is splintered among federal OSHA, state agencies and even local boards of health. Communication among them is muddled. As a result, there is little accountability for the failure of government watchdogs to keep workers safe from COVID-19.

The consortium documented that oversight of worker safety in the U.S. rarely results in meaningful consequences for companies that aren’t protecting workers. In Massachusetts, Walmart challenged OSHA’s investigation into the death of a worker. The company cited OSHA’s pledge to “use discretion” in holding retail employers responsible for COVID-19 cases in the workplace, and wasn’t penalized.

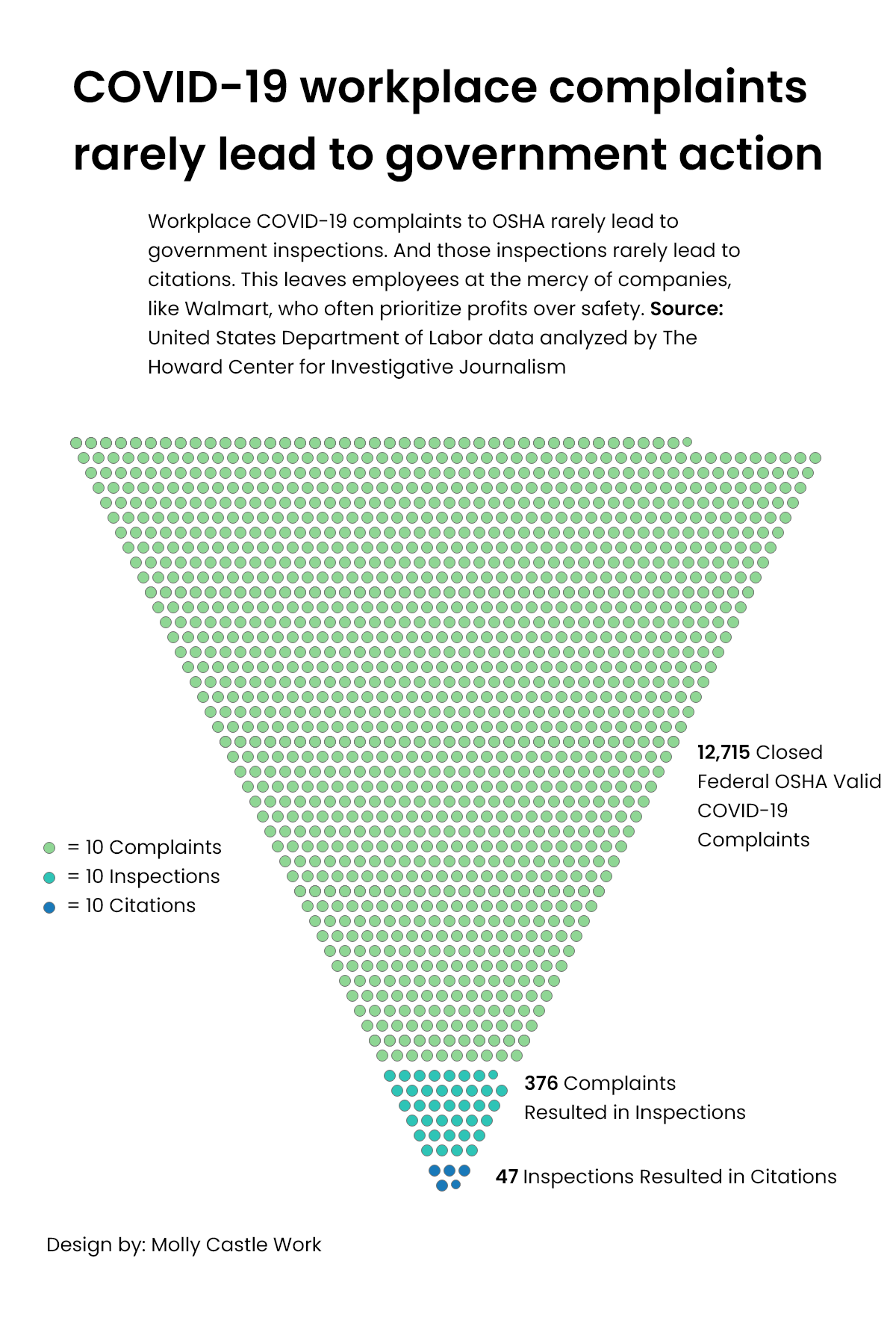

When workers submit COVID-related complaints, only a fraction lead to inspections, and even fewer result in a citation.

As of late March, 3% of closed COVID-19 complaints to federal OSHA offices deemed valid by the agency resulted in an inspection, 12.5% of which led to citations. The average penalty was $13,000. OSHA has reduced over a third of the fines.

For Walmart, slightly fewer complaints resulted in inspections — 2.6%. No inspections led to a citation.

Across 10 states with available data, multiple COVID-19 illnesses were recorded in at least 151 Walmart facilities. That’s one quarter of the company’s stores and distribution centers in those states.

During the Trump administration, OSHA was “asleep at the switch for the duration of the pandemic,” said Rick Claypool, a research director for Public Citizen, a consumer-rights advocacy group.

The Biden administration proposed an emergency standard April 26 that would give OSHA greater power to enforce workplace safety rules. Meanwhile, the cost of the 14-month delay since the pandemic began can be tallied in deaths and thousands of illnesses as the nation’s worker protection system stumbled and fell.

Cries for help rarely answered

In Grants Pass, Oregon, Walmart workers and customers filed more than two dozen complaints about the lack of COVID-19 safeguards in 2020 with the state worker-safety agency. The store allowed customers to enter without masks and allowed customers to remove masks once inside, a complaint from September read.

“Management tells us to say nothing and to not even bother … management with it,” the complaint said.

Between December and March, at least 18 people were infected in an outbreak linked to that Walmart. In January, while the outbreak was still active, another OSHA complaint alleged Walmart “may not be informing employees when in contact with a positive case for COVID-19 in the workplace.”

Karla Holman worked customer service at the Grants Pass Walmart and heard about cases through workplace rumors, never straight from her employer, she said, even as she came into close contact with an estimated 200 to 300 people each shift.

Walmart “was silent about it,” Holman said, at least until she was let go in January after taking time off to care for her grandfather, who caught the virus.

Other workers echoed Holman’s claims. Fernanda Alcantara, a Walmart associate in Rogers, Arkansas, said Walmart “did their best that if anyone in the store tested positive, they would keep it to themselves. … I think there were a lot more (cases) that they did not tell their employees.”

Store managers directed reporters to corporate officials. Walmart spokesperson Scott Pope said “we communicate with associates in stores where there has been a confirmed case.”

“Any time you operate more than 5,000 facilities across the country, there are going to be variances in how those facilities are managed,” Pope said.

John Howard, the head of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, said there are several barriers that prevent workers from complaining to OSHA — they might fear retaliation, face language barriers, lack authorization to work in the U.S. or be unsure of how to submit a complaint or to whom they should complain.

Since April 2020, OSHA has released an updated list, including company names, of complaints related to COVID-19 that the agency has deemed valid.

In Colorado, approximately 98% of all workplaces with reported COVID-19 outbreaks did not appear on OSHA’s list as of March 2021.

One-third of Walmart facilities in the state had recorded outbreaks, but none of those 37 facilities appeared on OSHA’s list – including two stores where a total of three employees died.

Twenty-one states have their own OSHA plans overseeing private businesses. They must meet all the federal standards but can impose stricter rules if they choose.

In those states, the rate of complaints was five times higher than in states where the federal government exclusively oversees workplace safety.

More complaints don’t guarantee more inspections. In Oregon, which is among the states with the most COVID-19 complaints for Walmart, only one complaint led to an inspection, and not until March 22 – more than a year after the pandemic started. As of March 24, at least 10 Walmart locations in the state were linked to outbreaks with over five cases, including a Hermiston distribution center linked to 124 recorded cases.

Pervasive hazards

A study published in Occupational & Environmental Medicine, an international, peer-reviewed journal, found that infection rates were significantly higher at a grocery retail store than in the surrounding community.

The study also found that in the store, workers who had direct contact with customers were five times more likely to contract COVID-19 than workers who did not.

The United Food and Commercial Workers International Union, North America’s largest food and retail union, said at least 34,700 of its members working in grocery stores had been infected by or exposed to the coronavirus and 155 had died. They didn’t count sicknesses or deaths connected to mom-and-pop grocery stores.

The pandemic “is a public-health crisis, but also a worker-health crisis,” said Peg Seminario, former head of occupational safety for the AFL-CIO.

Grocery and retail workers often earn low wages, so they may lack affordable health care and may be less likely to seek or receive treatment for COVID-19. Non-white and especially Black and Latinx workers are overrepresented within the industry, especially in the lowest-paying positions, and are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 due to racial discrimination in health care, housing and food.

Rebecca Reindel, director of occupational safety and health for the AFL-CIO, said the public-health response failed to protect employees because it focused on “cheaper measures, like cleaning and putting masks on people,” while it should also have included respirators, better ventilation and means to keep sick workers out of the workplace.

These measures shifted the burden to workers to protect themselves in an environment over which they have little control, Reindel said.

In addition to physical health risks, the inability to safely social distance at work poses “a significant risk factor for anxiety and depression,” according to the Occupational & Environmental Medicine article.

“Every day was like walking into a circus,” said Terry Croce, who has worked at a Stop & Shop in Rhode Island for 29 years.

“I think we’re all suffering from anxiety,” Croce said. Some of that comes from customers, who swear at workers and berate them. Croce said she had to break up a fight between two customers “in the produce department throwing potatoes at each other,” after one saw the other exit a car with a New York license plate – a state that was a COVID-19 hotspot at the time.

“I don’t think the corporate office realizes what their employees endured,” she said.

Save money. Live better.

In New Mexico, nearly every one of Walmart’s 54 workplaces has reported cases of employees testing positive for coronavirus, according to data from the state’s Environment Department.

Attorneys general in 11 states and the District of Columbia expressed concern in a letter to Walmart CEO Doug McMillon, citing reports of symptomatic employees remaining “undiagnosed due to the lack of testing capacity” and sick workers being pressured to work by store managers.

There were at least 85 complaints about Walmart or Walmart-owned Sam’s Club stores and distribution centers in those states after the letter was sent, and at least 387 across the country, according to the federal OSHA COVID-19 complaints database.

Walmart spokesperson Casey Staheli said Walmart has communicated with and responded to several government agencies, including OSHA, throughout the pandemic, but he did not provide specifics.

It is difficult to know the extent of COVID-19 spread in Walmart stores. The company tracks cases at a corporate level, but does not disclose them publicly, federal OSHA does not track outbreaks and states rarely disclose this data.

When states do provide COVID-19 data, their practices vary widely. Only some release the names of companies with COVID outbreaks. And there is no consistent definition of how many COVID cases constitutes an outbreak.

Reality check

Staheli said Walmart instituted a range of safety policies, including requiring facial coverings for associates and customers, limiting store hours and capacity, deep cleanings, temperature checks and health screenings of associates, installing plastic guards and implementing social distancing in all of its facilities. The company is not lifting the mask requirement at this time despite the fact that some states have ended mask mandates.

But workers said what’s on paper and what happens in the real world often don’t match.

Of 10 Walmart employees in five states interviewed by the Howard Center, just three said they felt safe from COVID-19 exposure at work.

Mishelle Fuller, a former Walmart worker in Rhode Island, said hand sanitizer was not provided, masks were not enforced and sick workers were told to keep working – including Fuller herself. When she became lightheaded one day in October and vomited in the bathroom, she said the store manager “told me to just go splash water on my face and get back to work.”

Fuller said after she tested positive for COVID-19 a week later, she tried repeatedly to call and text her department manager to let her know she was sick, and tried to relay messages through Walmart’s employee portal without success. On Dec. 10, Fuller said she got a Walmart letter stating she would be voluntarily terminated if she didn’t contact her manager by Dec. 7.

Walmart employees were required to wear masks beginning in April 2020.

Kellie Ruzich, a Walmart associate in Hermantown, Minnesota, said employees at her store are fired if they receive more than three warnings regarding the face-covering policy.

Customer mask mandates were not rolled out until July 2020 and workers said they were not strictly enforced.

Alcantara, the Arkansas Walmart associate, said management prohibits associates from asking customers to correctly wear their masks.

“Our safety is being disregarded in order to satisfy the customer,” Alcantara said.

Pope, the Walmart spokesperson, said the first step is flagging the customer and offering them a mask, then alerting a member of management if they refuse. His colleague Staheli would not comment on how Walmart management is trained to respond beyond “deescalation training.”

Jobs at risk

Some workers said they face retaliation if they complain about safety conditions to employers.

Lorinda Dudley was fired from a St. Albans, Vermont, Walmart in March 2020 after asking her manager for protective gear, according to a lawsuit she filed against Walmart in February. She was frightened after a customer coughed repeatedly at her checkout station.

Dudley said her manager rejected her requests and ordered her back to the register, then terminated her when Dudley said she would first need to buy her own protection. Walmart tried to block Dudley’s unemployment claim, saying she quit, Vermont Department of Labor records show.

“They (Walmart) didn’t have to put me through this,” Dudley said. “I just wanted to be safe. I tried everything to keep my job and then I lost it — and I don’t understand why.”

Walmart denies Dudley’s allegations and plans “to defend the company in court,” Pope said. “We take allegations like this seriously and have taken substantial measures during the pandemic to help protect the health and safety of our customers and associates.”

OSHA’s mission, its website says, is to “ensure safe and healthful working conditions for workers,” including protecting them from retaliation with programs like Whistleblower Protection.

Jordan Barab, deputy assistant secretary of OSHA during the Obama administration, told the Howard Center that OSHA’s whistleblower language is outdated and some claims take years to investigate.

OSHA missing in action

When state plans report violations, federal OSHA has “no consistent means” to determine if the violations are COVID-related, a U.S. Department of Labor spokesperson told the Howard Center. The spokesperson would not allow their name to be used.

As a result, there is no detailed national picture of how well the agency is protecting workers during the pandemic.

OSHA’s inaction has shifted some enforcement responsibilities onto local health departments.

From 2020 to 2021, Utah’s state OSHA referred about 20% of people complaining about COVID-19 hazards to local health departments. OSHA did not have a standard to address these complaints, said Eric Olsen, spokesperson for the Utah Labor Commission, which oversees the state’s OSHA.

But many local health departments have been overwhelmed with COVID-19 responsibilities.

“It just became the theater of the absurd,” said Shaun McAuliffe, director of the Hopkinton, Massachusetts, Board of Health. “They were just dumping onto the local health directors. We didn’t have the time. We didn’t have the training and we had no one else to roll it down to. We were at the bottom of the hill.”

In Maryland, a spokesperson for Gov. Larry Hogan said a state emergency COVID standard for workplaces wasn’t needed because the government gave local health officials the authority to close down unsafe workplaces, the Baltimore Sun reported. Asked by the Howard Center how many workplaces had been closed, a spokesperson for the Maryland Department of Health wrote that the agency does not maintain a central database of companies cited by local health departments and law enforcement for not complying with COVID-19 orders.

Seminario, Claypool and other worker advocates said OSHA has been missing in action during the pandemic.

The Department of Labor spokesperson said OSHA investigates every complaint, but it has modified its approach to enforcement, allowing for “remote inspections and informal methods of enforcement” in response to the pandemic, to “assure the agency’s effective and efficient use of resources … and the safety and health of OSHA compliance officers and employees.”

A February report from the Department of Labor’s Office of Inspector General compared OSHA results from 2019 to 2020. It found “OSHA received 15% more complaints in 2020, but performed 50% fewer inspections. As a result, there is an increased risk that OSHA is not providing the level of protection that workers need at various job sites.”

In lieu of on-site workplace inspections, “OSHA calls the employer, describes the alleged hazard(s), and then follows up with a fax, email, or letter to address the relevant hazard(s),” the OIG report said.

Eric Frumin, health and safety director for the Strategic Organizing Center, a labor-union coalition, said OSHA’s performance during the Trump administration was “a terrible betrayal of the (Occupational Safety and Health) Act, of the agency’s mission and the workers who trusted OSHA to take them seriously.”

President Joe Biden issued an Executive Order on Protecting Worker Health and Safety directing the Department of Labor to consider issuing by March 15 an emergency temporary standard to put in place enforceable worker protections in response to COVID-19.

The administration missed that deadline.

On April 26, OSHA submitted draft standards for interagency review and will issue a public update once the review is completed. “OSHA has been working diligently on its proposal and has taken the appropriate time to work with its science-agency partners, economic agencies and others in the U.S. government to get this proposed emergency standard right,” said a Department of Labor spokesperson.

In the meantime, state OSHA plans in California, Oregon, Michigan and Virginia enacted emergency temporary standards on their own. Virginia’s standard became permanent, and timelines vary in the other states.

Failure to protect

Lani Eklund said her mother, Yok Yen Lee, was scared of contracting the virus. Lee, a 69-year-old Chinese immigrant, was a greeter who was asked to stand outside the Quincy, Massachusetts, Walmart store and tell customers to wear masks, state workers’ compensation records show.

During the second week of April 2020, Lee wasn’t feeling well but told a coworker it was “just a cold,” Eklund said. On April 20, she was found unresponsive in her apartment, then was rushed to the hospital and put on a ventilator. Her daughter said Lee died May 3.

“(Walmart) didn’t share that there was an active cluster of cases in the store,” Eklund said. OSHA records from May 7 show that 16 other workers there also contracted COVID-19.

Walmart denied responsibility for Lee’s death and contested her family’s claim for workers’ compensation, according to state records. Eklund said she hired a lawyer and the company settled the matter months after her mother’s death.

Pope, the Walmart spokesperson, said the workers’ compensation claim was denied because “there isn’t a way to scientifically show that the conditions of any facility definitively led to confirmed cases.”

Lee’s death triggered an OSHA inspection at the Quincy store, which Walmart challenged, according to OSHA inspection records obtained by the Howard Center consortium.

The records show phone interviews were “interrupted and stopped prematurely” by Walmart officials when OSHA asked questions about Lee’s death.

In response to a subpoena issued by regional OSHA investigators, the records show Walmart cited OSHA headquarters’ own COVID-19 guidance in objecting to any investigation into whether coronavirus cases were work-related.

That guidance, part of an April enforcement memo, applied to retail and other employers outside of health care, emergency response and corrections. It said they “may have difficulty making determinations about whether workers who contracted COVID-19 did so due to exposures at work,” and so OSHA would exercise “enforcement discretion.”

On Dec. 30, 2020, more than six months after Lee’s death, OSHA closed the case, records show. It did not issue a citation.

In a February note to associates, John Furner, CEO and president of Walmart U.S., boasted about the company’s “amazing” increased sales.

“We did a lot right last year, and our customers rewarded us,” Furner wrote. “Thank you for an incredible year!”

Also contributing to this story were Victoria Daniels, Gabriel Pietrorazio, Aadit Tambe, Carmen Molina Acosta, Elisa Posner, John Kwak, Nicole Noechel, Rachel Logan, Jummy Owookade and Manuela Lopez Restrepo from the University of Maryland; Jackson Ripley, Nathan Lederman and Alaina Mencinger from Boston University; Abby Zimmardi, Mary Hennigan and Rachell Sanchez-Smith from the University of Arkansas; Cade Cannedy from Stanford University.

You must be logged in to post a comment.