Private funders paid for a member of the U.S. House of Representatives or their staff to travel overseas more than 4,000 times in the past decade.

The bill for the vast majority of those trips was footed by nonprofit organizations, including prestigious think tanks such as the Aspen Institute and German Marshall Fund, according to an analysis of House travel disclosures by the University of Maryland’s Howard Center for Investigative Journalism.

Good government advocates said that’s a problem because foreign governments often donate to nonprofits, but nonprofits are not legally required to disclose where their money comes from.

Ben Freeman, author of a 2020 study on foreign-funded think tanks, said the lack of transparency allows foreign governments to indirectly underwrite luxury trips in a practice he calls “influence laundering.”

Anna Massoglia, editorial and investigations manager at OpenSecrets, a congressional watchdog organization, agreed the practice raises questions.

“When a foreign government funds a trip, there may be more perceived risk of the lawmaker or congressional staffer appearing to be unduly influenced by foreign interests,” she said. “Travel sponsored by a think tank can give more of an appearance of independence and objectivity, which may help avoid any negative associations with direct funding from foreign governments.”

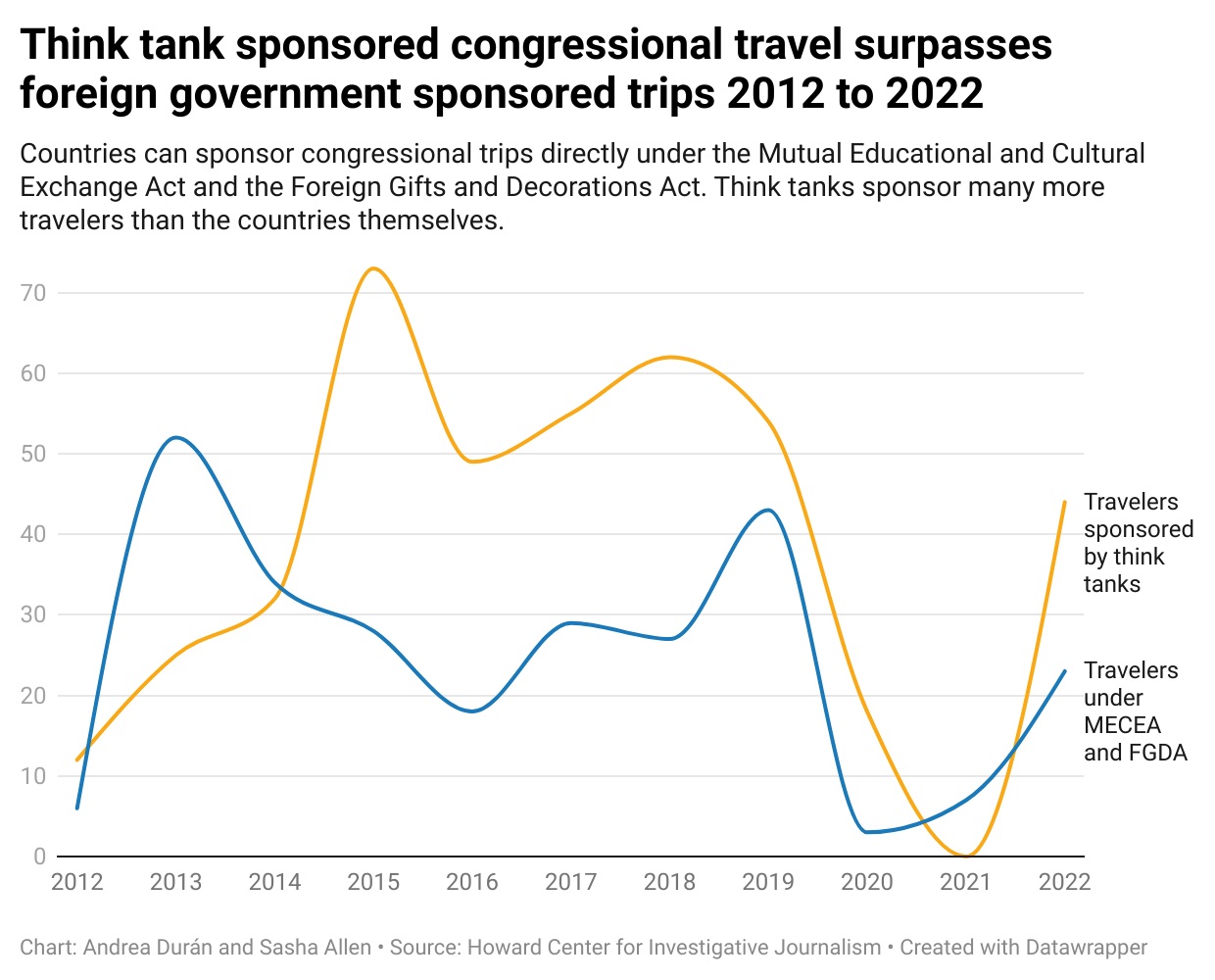

The Howard Center analysis found a House member or staff member reported taking an international trip funded directly by foreign governments approximately 270 times from 2012 through 2022. They took nearly four times as many foreign trips, just over 1,000, that were sponsored by think tanks that disclosed on their websites that they received foreign government funding.

Only 13 of the approximately 20 think tanks that sponsored foreign travel disclosed some of their funding on their websites. The Howard Center analysis, which used AI to pull think tanks from the sponsors list, further revealed that six of these 13 think tanks sponsored travel to their donor countries.

Travel by House members and their staff to countries whose governments contributed to the sponsoring organization made up more than 40% of overall foreign trips sponsored by think tanks.

The German Marshall Fund sponsored foreign travel for a member of the House or their staffer 133 times.

Rep. Steve Cohen, D-Tennessee, co-chair of the U.S. Helsinki Commission, was a traveler to the German Marshall Fund’s annual Brussels Forum in June 2022. The forum historically focuses on transatlantic issues, and in 2022, there were numerous discussions surrounding Russia, Ukraine and the state of Russia.

Cohen has pushed for legislation in support of Ukraine for years. After the trip, he sponsored three resolutions condemning Russia, urging President Joe Biden to terminate Russia’s participation in any aspect of the United Nations because of Russia’s war against Ukraine and pushing for more aid to Ukraine from the U.S. and allies.

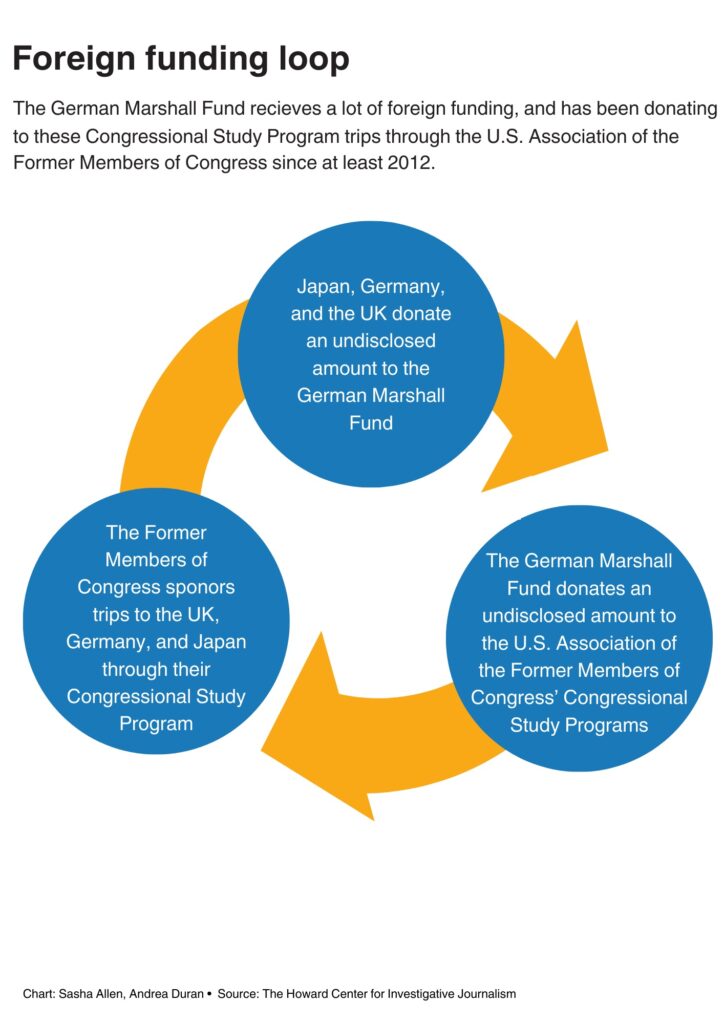

When Japan donated money to the German Marshall Fund from 2012 to 2022, the fund, in turn, gave an undisclosed amount to the United States Association of Former Members of Congress, a nonprofit organization of current and former legislators.

In February 2019, the Former Members of Congress paid for Rep. Billy Long, R-Missouri, to fly to Japan, where he discussed foreign affairs over five-star dinners, and took tours of historical and cultural sites.

Over the seven days of meetings, Long met with the Japanese minister of foreign affairs and minister for trade and energy, as well as leaders from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Two months after he returned, Long co-sponsored a resolution calling for the “strengthening of ties” between the U.S. and Japan.

Records show the German Marshall Fund has made annual donations to the Former Members of Congress, although the amounts were not disclosed.

Of the 133 times the fund has directly sponsored travel for a member of Congress or staffer since 2012, 116 trips involved visits to donor countries — mostly Germany.

The press officer of the fund, Chris Schaefer, noted the fund is “committed to the idea that the United States and Europe are stronger together” and, as part of this mission, it has “facilitated travel for learning and exchange of ideas for Members of Congress, always in full compliance with congressional ethics rules.’’

“As a valued partner institution, GMF has given an annual grant to the Association of Former Members of Congress (FMC) to be used in support of the Congressional Study Group on Germany,” he said via email. “Programs like the Congressional Study Group on Germany play a pivotal role in safeguarding democratic values and ideals through effective and substantive dialogue.”

The Former Members of Congress have not sent a congressional delegation to Germany since 2017, yet they have continued to receive undisclosed amounts from the fund since at least 2022.

By far, the Aspen Institute sponsored the most trips. However, these are held through the organization’s congressional program, which does not receive foreign funding according to a statement provided by an Aspen Institute spokesperson.

“The Aspen Institute is comprised of dozens of programs and initiatives, which receive funding from many different sources in support of their specific areas of work,” the spokesperson said. “The large majority of our programs, including the Congressional Program, do not receive any kind of domestic or international government funding.”

Funding disclosures for the Congressional Program are not available. The Aspen Institute only discloses the funding for the entire organization.

The sharing of money among nonprofits is legal but troubling because of the lack of transparency, Freeman said.

“When you start talking about a think tank, which is a nonprofit, funding another nonprofit, then you’re adding even more layers of complexity to what’s already a very opaque funding environment,” he said. “The more you see these levels of money changing hands, the harder it’s going to be for the average member of the public to understand where the money is coming from.”

Think tanks often carry significant weight in policy debates in Washington. Their researchers contribute opinion pieces to major media outlets and appear on broadcasts explaining the issues of the day. They contribute language that ends up in the laws passed by Congress, Freeman said.

On Oct. 2, 2022, five congressional staffers arrived in the United Arab Emirates on an all-expenses trip paid for by the Atlantic Council. It featured meetings focused on clean energy as well as briefings from oil and energy companies focused on their efforts to ensure a more sustainable oil and gas supply. The staffers worked on energy and environmental policy for their House bosses.

Three months later, Frederick Kempe, president and CEO of the Atlantic Council, wrote a column for CNBC praising the United Arab Emirates’ plans to fight climate change.

What Kempe did not mention is the UAE, a major oil-producing country, donated at least $1 million to the Atlantic Council in 2022, had given the think tank a minimum of $1 million annually since at least 2019 and the Atlantic Council had sponsored three tours to the UAE since 2018, with a total of 12 individual congressional staffers traveling to the UAE within those years.

When The Washington Free Beacon reported on the UAE donations to the Atlantic Council, CNBC added an editor’s note to Kempe’s column saying he had not disclosed the financial relationship “as well as the obvious conflict of interest” and the column did “not meet our standards of transparency.” The Atlantic Council then issued a statement to the Free Beacon apologizing for not disclosing their ties to the UAE.

Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa and Rep. Jack Bergman of Michigan, both Republicans, want to shine a light on the murky world of think tank donations.

They are currently sponsoring the Think Tank Transparency Act in the House and Senate. It would require think tanks to disclose their donors.

“The American people deserve to know what these think tanks are up to, and who they’re working for,” Bergman said in a news release on the legislation. “The assumption that they are non-political, pseudo-academic entities advocating for policies that are in the national interest is no longer accurate, given the increasing amount of funding they receive from foreign governments, often earmarked for specific projects.”

The legislation is currently stalled in Congress.

You must be logged in to post a comment.