U.S. representatives and their staff have taken at least 17,000 trips since 2012 that were paid for by private parties, many of them nonprofits with deep ties to lobbyists and special interests.

Lobbyists and groups that retain them have legally gotten around major reforms meant to severely restrict their involvement in congressional travel by spinning off nonprofits or by sitting on nonprofit boards that pick up the travel tab.

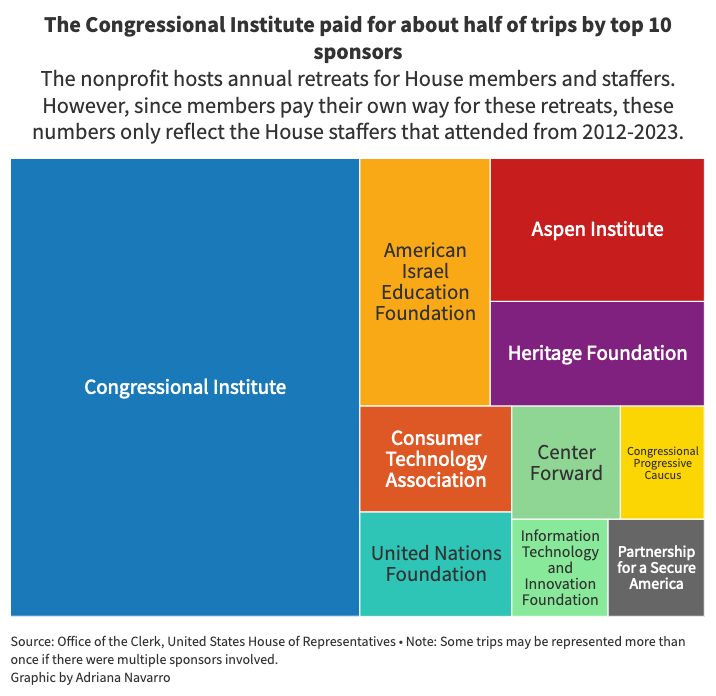

Leading the way: the Congressional Institute, a nonprofit little known outside Washington that alone has sponsored a quarter of the trips — 4,200 and counting, according to an analysis of House travel disclosure data from 2012 through 2023 compiled by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland.

At least 75% of the institute’s board members over that period were registered lobbyists while serving on the board, according to tax and lobbying records. The Congressional Institute bankrolls the trips with nearly $3 million in annual membership dues from private interest groups such as Business Roundtable and the American Hospital Association.

But because the nonprofit itself is not registered to lobby, it is free to pay for multi-day trips to luxury hotels and resorts along the mid-Atlantic coast, where its guests might rub elbows with private-sector institute members who pay as much as $27,500 annually for access to the invite-only retreats.

Kelle Strickland, president and CEO of the Congressional Institute, defended the role lobbyists play in the organization.

“Many of the professionals that work downtown in D.C. are former Hill staff, and they provide an incredible insight to the changing needs of Congress at the member level and at the staff level,’’ she said.

The Congressional Institute is not an outlier. The Howard Center found that nine of the top 10 sponsors of privately funded Congressional travel throughout the last decade have had current or former registered lobbyists on their boards or in leadership.

Each of the approximately 17,000 trips in the Howard Center’s database represents travel by one U.S. House member or staffer, either alone or as part of a delegation and sometimes with a family member. The vast majority of trips, at least 75%, were taken by staffers, who can play important roles in shaping policy and drafting legislation.

The much smaller Senate reported more than 2,600 trips during the same period, but

Senate disclosure forms do not provide sponsors or destinations in a format that can be readily analyzed.

In addition to travel disclosures, nonprofit tax records and lobbying registrations, the Howard Center examination of House travel used data collected by OpenSecrets, a nonpartisan government watchdog organization, and by LegiStorm, a public affairs information platform, to document the extensive links between lobbyists and travel sponsors.

The connector role

With only a few exceptions, the Congressional Institute trips were for staff travel — often to what it bills as “family-friendly” conferences for top aides such as chiefs of staff, communications directors and legislative directors.

The organization also sponsors conferences for their bosses, most notably the annual House Republican retreat that took place at The Greenbrier luxury resort in West Virginia in March. However, it doesn’t cover the members’ travel or lodging.

Strickland joined the Congressional Institute last year after two decades working in the House, most recently as legal counsel for the chairman of the House Ethics Committee, the body in charge of approving gift travel.

The Congressional Institute was incorporated as a nonprofit in 1987 to hold educational conferences that, according to its website, provide “space for Members and staff to discuss legislative priorities and strategies as well as develop professional relationships with each other and experts in their fields.”

The institute functions as a middleman by providing opportunities for lobbyists to network and build relationships with members and staffers, said Anna Massoglia, editorial and investigations manager at OpenSecrets, which tracks money in politics.

“They don’t have specific things that they’re pushing for, but they connect members of Congress with other people who might,” Massoglia said.

Lobbyists have been part of the Congressional Institute from the beginning. Kenneth Duberstein, founder of the Duberstein Group lobbying firm and former chief of staff to President Ronald Reagan, was the Congressional Institute’s founding board chair.

Today, 11 of the 12 Congressional Institute board members are current or former federal lobbyists. They have worked for some of Washington’s top lobbying firms such as the Duberstein Group, Bockorny Group and H&M Strategies. The board members’ recent clients are major economic players across the Fortune 500 list, including Exxon Mobil Corporation, Toyota, JPMorgan Chase and Meta (formerly known as Facebook).

The Duberstein Group declined to comment for this story. The Bockorny Group and H&M Strategies did not respond to phone calls and emails, nor did Congressional Institute board members.

The one board member who has not registered as a lobbyist, according to disclosure forms, is Michael Sommers, president and CEO at American Petroleum Institute. API is a national trade association that represents the oil and natural gas industry, and spent over $6.1 million on lobbying in 2023 alone. API did not provide a comment.

Some past and current clients of lobbyist and institute board members David Bockorny, Anne Bradbury and Dan Meyer have made yearly contributions of $27,500 to the Congressional Institute. They include the Business Roundtable, an association of CEOs, from 2020 to 2022 and the American Hospital Association from 2019 to 2021. Business Roundtable and the American Hospital Association declined to comment.

Congressional Institute officials declined to disclose who its members are and whether membership has increased in recent years. Lisa Camooso Miller, the institute’s media spokesperson, confirmed “a representative of dues-paying partners are invited to attend the conferences” for House members and staffers. “Private sector partners pay their own room, food and other conference expenses,” she added.

On travel sponsor forms that are submitted to the House Ethics Committee, the Congressional Institute checks a box attesting it hasn’t “accepted from any other source, funds intended directly or indirectly to finance any aspect of the trip.”

But in fiscal year 2023, 86% of revenue was derived from membership dues and more than half of expenses were for hosting congressional trips.

Craig Holman, a public interest lobbyist at Public Citizen, calls the Congressional Institute’s private sector partnerships “obvious influence peddling.”

Holman helped write a major congressional ethics reform bill passed in 2007 that restricted lobbyist involvement in privately funded travel. He told the Howard Center it can be difficult to limit lobbying freedoms due to the constitutional right to petition the government.

“I would like to try to end that kind of activity. But I’m always, you know, sort of checked with the First Amendment stuff,” he said. “How far can I go to try to avoid money buying influence like that?”

Networks of organizations emulate ‘money laundering’

Congressional travel rules impose greater restrictions on organizations that are registered to lobby or employ staff to lobby for them. Those registered to lobby are generally limited to sponsoring trips of no more than one day, unless a special waiver is received for a two-day trip. Lobbyists may not play any significant role in organizing or participating in the trip.

However, the rules do not prohibit nonprofits such as the Congressional Institute from having lobbyists on their boards and in their programs. Nor do the rules stop organizations involved in lobbying from creating and funding nonprofits that don’t lobby — and therefore can sponsor travel under less restrictive rules.

Groups will often create a network of organizations, Massoglia said, allowing them to get around rules restricting what different nonprofits can fund, how much they can spend on lobbying and whether they can donate to campaigns.

“It absolutely emulates money laundering,” Massoglia said. But she said it’s legal, and makes it difficult to regulate gifts and travel for members of Congress.

“It provides a way to really get around the intent of the law,” Massoglia said.

Campaign contributions, congressional travel and hosting fundraisers all go hand-in-hand when it comes to lobbyists gaining favor with elected officials, public interest lobbyist Aaron Scherb told the Howard Center.

“Those are the three big ways that I think corporations, for-profit entities, special interests can try to curry favor with elected officials to try to get their agenda done,” said Scherb, the senior director of legislative affairs at Common Cause, an ethics and advocacy watchdog focused on government transparency and accountability.

These groups can even employ the same staff and share an office but serve different functions based on the legal restrictions on each type of organization.

The American Israel Public Affairs Committee and its charitable arm serve as one example of nonprofits intimately linked in a way that allows lobbyists to legally skirt what reformers wanted the law to achieve with the 2007 reforms.

The American Israel Education Foundation, AIPAC’s charity organization, sponsored over 800 congressional trips – primarily for House members – from 2012 through 2023, according to the Howard Center analysis. This makes it the second-largest sponsor of private travel for the House.

AIPAC spokesman Marshall Wittmann said in 2023 that the two organizations “are distinct entities.” However, AIPAC is listed as the “direct controlling entity” of AIEF in AIPAC’s federal tax disclosure forms.

By sponsoring about 75% of privately sponsored House travel to Israel, AIPAC ensures its perspective remains the dominant lens through which lawmakers and staffers receive on-the-ground exposure to the impacts of U.S.-Israel policy and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

This allows it to try to monopolize what it means to be pro-Israel on Capitol Hill, according to Dov Waxman, a professor and director of the UCLA Y&S Nazarian Center for Israel Studies.

AIPAC’s more moderate political rival, J Street, followed a similar strategy and organized 129 trips for House members and staffers between 2012 and 2023 through its 501(c)(3), the J Street Education Fund.

This system allows J Street and AIPAC to sponsor multi-day travel abroad. Domestically, organizations also create sister nonprofits to legally get around laws on single-day travel for sponsors that retain lobbyists.

After the 2007 ethics reforms, the American Sugar Cane League — the co-op that represents Louisiana’s sugar industry — could no longer retain both its longtime lobbying presence in Washington and continue sponsoring multiday congressional travel. So sugar industry insiders tied to the league, including current and former American Sugar Cane League board members, formed the Louisiana Sugar Cane Foundation, which eliminated the need to choose between the two.

The foundation has sponsored about a third of House staffers’ visits to sugar-growing regions. And between 2012 and 2023, sugar interests sponsored more congressional travel than any other branch of the agribusiness sector.

Sugar-sponsored travel reached its apex amid consideration of the 2018 Farm Bill — a significant bill setting policy on dozens of agriculture-related issues, including whether limits on imported sugar would remain in place. Without those protections, American sugar producers feared they could no longer compete with foreign sugar producers.

Ethics rules aren’t ‘worth the paper they’re written on’

House ethics rules restrict lobbyists from outright organizing trips for members and staff. However, the rules do not prevent nonprofits that retain lobbyists or are funded in part by lobbying organizations from giving lobbyists and influential industry officials a platform as speakers or attendees at events.

Such is the case with the Consumer Technology Association.

Every January, the tech trade association and registered lobbying organization flies dozens of congressional staffers to Las Vegas for a day of programming at the Consumer Electronics Show.

Onsite, representatives from CTA member companies such as Microsoft, Amazon and Meta have the opportunity to discuss the laws they’d like to see passed. These officials often are not registered lobbyists, but their goal is to persuade Congress to pass legislation that benefits the tech industry.

“Unfortunately, it’s kind of the norm,” Meredith McGehee told the Howard Center of lobbyist involvement at CES. McGehee is an independent expert in government ethics and money in politics. “The reality has been that with a little good lawyering and not much originality, you can pretty much get around these rules to do whatever you want.”

The rules requiring lobbyists to be hands-off in travel, she added, are “not really worth the paper they’re written on.”

The House Ethics Committee does not disclose whether they reject private trip requests that violate the rules. Aaron Scherb called the committee’s review process “a black box” and said, “There’s no way to see how much or what kind of due diligence they’re actually doing.”

Tom Rust, chief counsel and staff director for the House Ethics Committee, declined to comment.

The Congressional Institute also packs its trip agendas with keynote speeches and panels given by representatives of major lobbying firms in Washington. Eleven lobbyists addressed top House aides in February 2024 at its three-day Legislative and Communications Directors Retreat at the Hyatt Regency Chesapeake Bay Golf Resort, Spa and Marina in Cambridge, Maryland.

The Howard Center reached out to nine House staffers who took that trip or others sponsored by the Congressional Institute. They declined to comment or did not respond.

Among those in Cambridge were Ben Nyce, deputy policy director to the House Republican Conference, and Hannah Morrow, legislative director for U.S. Rep. John Rutherford, R-Florida.

In their disclosure reports, Nyce cited the meeting as an opportunity to “strengthen professional relationships” and Morrow said she attended “for leadership training and policy sessions that will enhance my work to achieve my boss’s policy goals.”

The Congressional Institute paid about $1,882 for Morrow and her husband’s lodging, meals and room rental, and $1,127 for Nyce, their reports say.

Foreign governments funnel trip money via American think tanks

Domestic groups aren’t the only ones trying to influence U.S. policy through nonprofits. American think tanks such as the Atlantic Council are major sponsors of congressional trips abroad and receive millions in funding from international governments, serving as a domestic conduit for foreign governments to influence members. Of the 1,010 international trips sponsored by think tanks that received foreign funding, just over 40% were to countries that donated to the sponsoring organization.

The Atlantic Council has received funds and sponsored trips to the United Arab Emirates, Turkey and Lithuania. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the council became one of the highest think tank recipients of foreign funding, according to data for a forthcoming think tank report from the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft provided to the Howard Center.

“It’s an ultimate lobbying opportunity for a foreign government,” said Ben Freeman, director of the Democratizing Foreign Policy program at the Quincy Institute, a think tank that advocates for diplomatic solutions in U.S. foreign policy. “I would even dare say that trips like this are worth their weight in gold. I think they’re more valuable even than these foreign governments’ regular lobbying operations in D.C.”

More ethics reform will happen ‘only on the heels of scandal’

Craig Holman said Congress will only impose rules on itself if the public clamors for change. The last major overhaul of lobbying rules in 2007 resulted directly from outcry over Jack Abramoff’s flagrant wining and dining of lawmakers.

From 1994 to 2004, Abramoff was a high-profile lobbyist who later admitted to providing lawmakers with golf trips to Scotland, box seats to NFL games and campaign donations. In return, he sought their commitment to support and pass legislation that favored his private-sector clients.

After Senate inquiry into his dealings set off a series of investigations, Abramoff was sentenced to 48 months in prison on charges involving corruption, conspiracy, tax evasion and fraud. He served 43 months. The public firestorm that followed his conviction spurred the passage of the Honest Leadership and Open Governance Act in 2007.

“Members of Congress won’t start regulating themselves if it’s just left up to them,” Holman said. “They will start coming out with these regulations when the public gets involved. And the public gets involved only on the heels of scandal.”

ProPublica provided data for this story.

A version of this story appeared on Politico.

You must be logged in to post a comment.