Affordable Care Act gives lifeline to young cancer patient

Affordable Care Act gives lifeline to young cancer patient

Story and photos by Aaron Rosa \ Page design by Ana Hurler

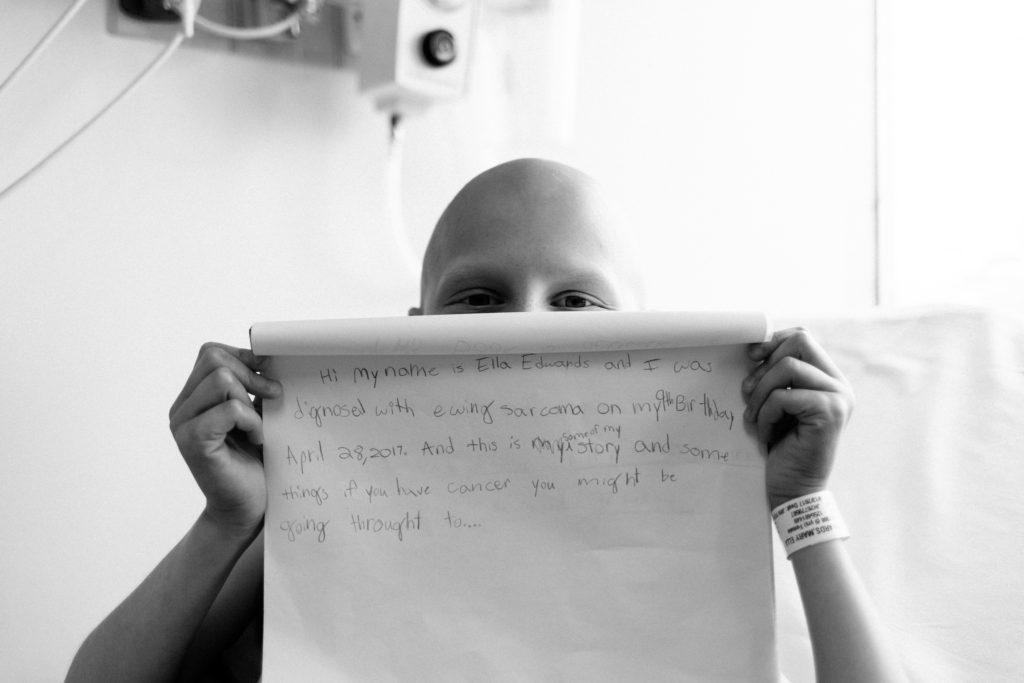

ELLA EDWARDS’ LIFE CHANGED ON HER NINTH BIRTHDAY.

Presents sat unopened in her family’s Davidsonville house in April, while at Johns Hopkins Hospital her parents told her she had Ewing’s sarcoma, a cancerous tumor growing in her stomach. The disease is so rare that only about 225 children in the United States are diagnosed each year.

The Edwards family entered a new reality of oncologists and treatments.

“It was crazy fast,” Jen Edwards said. “We were taken up to oncology, and I was thinking, what are we doing here? There are kids with cancer here.

“At that point we weren’t even thinking of insurance.”

The Edwards family hadn’t been following the congressional debates over the repeal of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, also known as “Obamacare.” But now they, like millions of other Americans, would have to deal with a pre-existing condition — which before the Affordable Care Act meant companies could refuse insurance.

Though Congress and the Trump Administration have tried — and failed — to repeal President Barack Obama’s healthcare law, these patients remain worried about their future.

“The ACA was something I never paid attention to,” Jen Edwards said. “You just assume your child is never going to get sick and be healthy all their lives.”

Brian Edwards runs Hague Quality Water, a water treatment company, owned by his father, that has been in his family over 20 years. He purchased health insurance for his children, which, he said, cost less than what he would have to pay through work.

Jen and Brian Edwards have five children (left to right): Addison, 11, Ella, 9, Grace, 7, Benjamin, 5, and Annabelle, 3. Ella was diagnosed in April with Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare form of cancer.

A week before Ella’s birthday, a stomach flu hit the family, but Ella did not respond to the usual medications.

Doctors at Anne Arundel Medical Center found a grapefruit-sized tumor pressing against her bladder and transferred her immediately to Johns Hopkins University for further testing.

There, the doctors diagnosed the cancer. And two days after her parents took her to the hospital for what they thought was a stomach bug, Ella began receiving chemotherapy.

At Hopkins, Jen Edwards recalls, hospital administrators made a crucial discovery: Ella had been admitted through the emergency room. If Ella was discharged, Johns Hopkins would not readmit her because, though the emergency visit was covered, Hopkins did not accept her insurance for continuing treatment, a staff member confirmed.

They stopped the family from leaving. The administrators recommended that Brian Edwards purchase a new plan, under “Obamacare,” that would cover Ella’s future treatment — avoiding a bill of $80,000.

In a stroke of luck, Hague Quality Water was in a two-week period where the business could choose a new insurance provider for their employees. Brian Edwards switched his company’s coverage to Evergreen Health, a plan on the state health exchange that offered in-state health insurance for Ella’s condition.

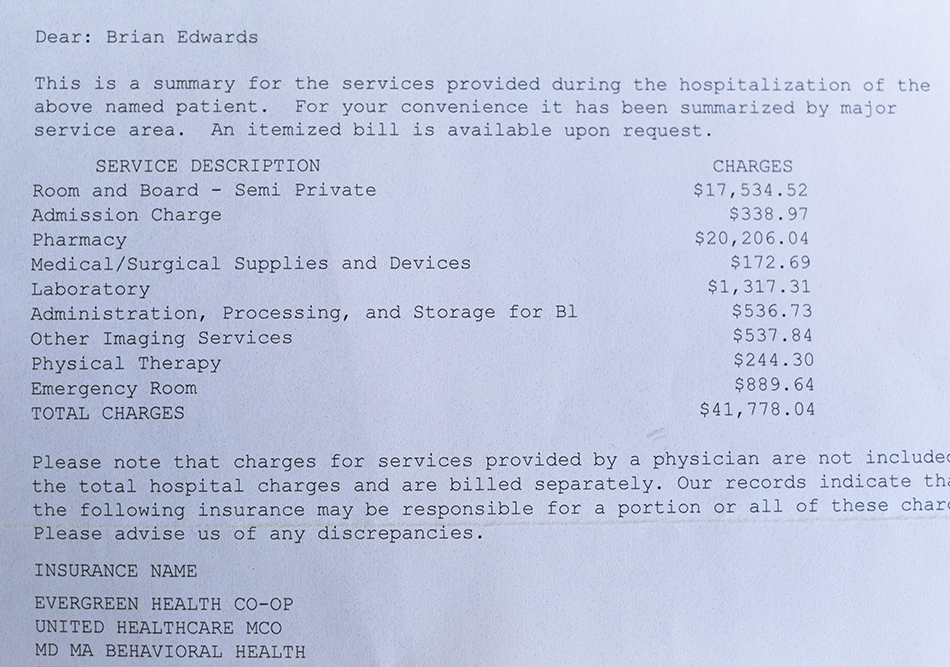

Jen and Brian Edwards sort through bills for Ella’s treatment. To date, the family’s insurance plan through an Affordable Care Act provider has absorbed over $200,000 in medical costs.

Ella’s newly diagnosed cancer is included on a list of declinable conditions that would have caused her application for insurance to be automatically denied in all but five states before the health care law, according to a study by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Evergreen Health’s monthly premium is $1,900, nearly 30 times the $66 premium he previously paid for insurance covering all his children — the policy from a company that Johns Hopkins would not accept.

“Even if you can’t pay the bills in that moment, you’re still going to do the treatment,” Jen Edwards said.

She leafed through a thick, worn binder filled with letters from doctors, scraps of paper with hastily jotted notes, and bills — dozens of bills.

Ella’s initial seven-day hospitalization topped $41,000, including $17,000 for room and board, and $20,000 for her first round of chemotherapy.

A statement from Evergreen Health, the family’s insurance provider, details the cost of Ella’s initial hospital stay and treatment in April. Her first round of chemotherapy cost more than $20,000.

Four months of cancer treatments, visits with specialists, and hospitalizations racked up over $200,000. All but their $1,500 deductible was paid by their insurance company.

Before the Obama health care law, those costs led many families to bankruptcy.

A study conducted by Harvard University and published in the American Journal of Medicine in 2007 found that from 2001 to 2007, bankruptcies attributable to medical problems increased by 50 percent and comprised 67 percent of all bankruptcies in the United States.

Cost of life, a metric used to quantify one year of life with cancer treatment, rose from $54,100 in 1995, to $207,000 in 2013. This statistic does not include expenses like surgery or home care, nor does it account for the loss of income resulting from a chronic illness.

Brian and Jen Edwards held a different view of the health care law before Ella’s diagnosis. Back then, they viewed “Obamacare” as socialization of health care.

“For me, Ella’s cancer changed my perspective about the Affordable Care Act,” Jen Edwards said.

“Knowing some of these children that are also at Hopkins, I know their families can’t afford it,” she trails off. “Every child should get care.”

Jen Edwards has quit her job at a local church to care for Ella.

Jen Edwards and her daughter Ella play cards to pass the time during Ella’s chemotherapy treatments. Each treatment session is eight hours long, and Ella has completed 11 sessions since her diagnosis in April.

Brian Edwards supplements his work-provided policy with an additional policy to cover the more expensive drugs not covered by Evergreen.

The additional policy is income-based. With five children and a single income, the Edwards family qualifies for its insurance. But if Jen Edwards were to resume working and the family income increased, they would be ineligible.

But even with government subsidies, the Edwards family’s health insurance policies cost him over $2,500 a month.

“It’s overwhelming,” Brian Edwards said. “I don’t know how people do it without insurance.”

Ewing’s sarcoma has a good prognosis if it has not spread. Ella’s has spread to her lungs.

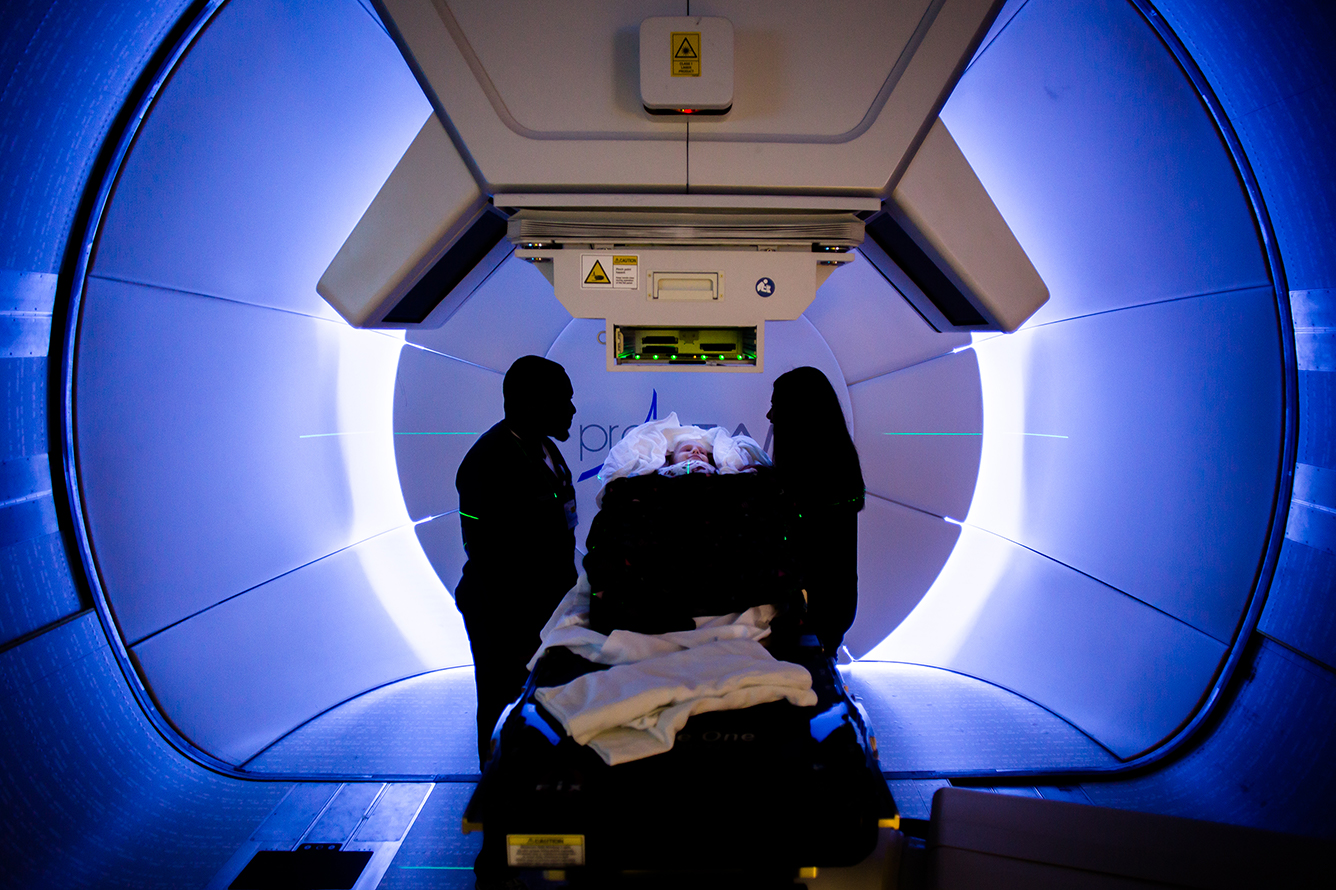

Staff at the Maryland Proton Treatment Center align Ella for proton radiotherapy treatment, which focuses a pencil-width beam of protons on Ella’s tumors as a non-invasive alternative to surgery.

Ella has completed 11 of 14 rounds of chemotherapy and is undergoing an eight-week proton radiotherapy treatment plan in lieu of a surgery that would have removed two of her vertebrae.

The family’s life is now shaped by cancer.

Ella and her siblings manned a lemonade stand on the side of a nearby road this summer to raise money for Ewing’s sarcoma research. The family visited Hershey Park. And Ella attended a special week-long camp sponsored by Johns Hopkins University Hospital and staffed by medical personnel.

Ella and her siblings run a roadside lemonade stand to collect donations for Ewing’s sarcoma research.

What they did not do this summer was watch the healthcare debate on television.

Brian Edwards canceled their cable TV subscription. The Edwards children watch cartoons on Netflix.

“Nothing good comes from watching the news,” Brian Edwards said.

But the next wave of bad news didn’t come through the television. It came in the mail.

As a non-profit, Evergreen could no longer cover the costs of its clients, and in a final desperate measure, converted to a for-profit model and sought an outside investor.

Investors dropped out of the Evergreen acquisition deal this summer. In August, the Edwards family received a letter from Evergreen Health announcing that it would be going out of business, honoring existing contracts but closing its doors for good in 2018.

Ella walks into the room where she will receive the third of six proton radiotherapy treatments.

“We’ve been lucky to have coverage so far,” Brian Edwards said softly. “But with Evergreen going out of business, next year is going to be very different.”

Brian Edwards again switched his company’s insurance from Evergreen to Maryland Blue Cross Blue Shield.

His monthly premium increased by $400.

Ella stretches after a chemotherapy session.