COLLEGE PARK – Cash-strapped Maryland county leaders say they can’t afford to pay their share of rising costs for schools and are asking the state to back off of a requirement to match state education funding dollar-for-dollar.

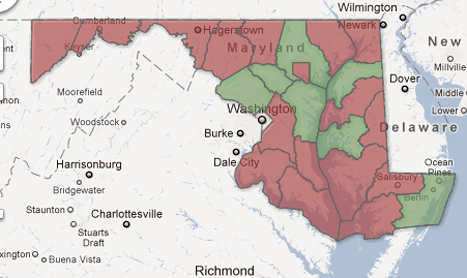

Counties are responsible for splitting education costs with the state. But, education groups say about a third of Maryland counties are not matching state funding at the level required under Maryland law.

That includes two of Maryland’s largest school districts, Montgomery and Anne Arundel counties, and five smaller districts – Dorchester, Kent, Queen Anne’s, Talbot and Wicomico counties – according to an analysis by the Maryland State Education Association.

County leaders say they can’t fully match state funding because they have been hit hard by a reduction in property tax and income tax revenue over the last few years.

Even with budgeting shortfalls, local leaders still need to uphold their commitment to school funding, House Speaker Michael E. Busch said.

“We are in the midst of trying to create a system that is an equitable system for all the counties in the state to maintain their fair share of the contribution for education,” he said.

Del. Norman Conway, D-Wicomico, who chairs the House Appropriations committee, and other state legislators are expected to meet Friday in Annapolis to listen to county leaders’ concerns about education funding.

“We called the meeting because we’re getting some indications that there are some challenges for the counties that are not on the positive side,” Conway said.

The push by education groups and some legislators to force counties to spend more money on education comes as Gov. Martin O’Malley moved this week to shift more of the burden of paying for education to local governments.

On Wednesday, O’Malley released a proposed budget that would require counties to pay about half the total cost for teacher pensions, which makes up a sizable share of the state’s education budget and is estimated to cost $946 million in the next fiscal year.

“The stakes of this conversation just got a lot higher if the governor is preparing to shift pension costs to counties,” said Michael Sanderson, executive director for the Maryland Association of Counties. “You are forcing them [the counties] to come up with a big pile of cash for a commitment to school funding. Suddenly the stresses of their budgets get much worse.”

School funding has been a top priority for O’Malley. In his proposed budget for the next fiscal year, the governor wants to spend approximately $5 billion on education – an increase of $109 million over last year — and more than $373 million on new construction projects for schools.

County leaders say the sputtering economy has weakened their tax base, forcing them to make tough spending decisions that have affected schools.

In Montgomery County, cuts to school funding have resulted in crowded classrooms, frozen teacher salaries and reductions in hours for more than 5,000 part-time staff, according to the Montgomery County Education Association.

“Our…funding now is $70 million less than what it would have been had Montgomery County funded schools at the required level set by the state,” Tom Israel, executive director of the Montgomery County Education Association said.

Counties are required to fund education at the same level as the previous year to be awarded an increase in state aid. This requirement, known as “maintenance of effort,” ensures that state funds are matched each year by local governments.

In Talbot County, where the primary source of revenue comes from property and income taxes, officials did not match maintenance of effort funding this year for the first time ever.

The county spent approximately $32 million on education funding this year, a cut of $1.8 million from the year prior.

“It’s a very tough decision to cut school funding. Obviously education is a high priority, and we take it very seriously,” County Manger John Craig, said.

For several years Talbot County has seen a drop in revenue, primarily due to a cap on property taxes, Craig said. The county budget decreased by more than $20 million over the last five years, he said.

Like Talbot, most counties spend about half of their budget on schools. And since the county cannot tell school boards how to spend money they allocate, county leaders feel shut out of the process, Sanderson said.

“We’ve reached a point where the counties are almost irrelevant in the budgeting process. They wish to save money, consolidate services, equalize benefits for school employees and have school staff participate in furloughs, like almost every other department in every county, but for education we can’t,” he said.

But state education advocates say the counties are taking advantage of what they call a loophole in the maintenance of effort requirement, allowing them to reduce school funding without penalties.

The advocates say the state should penalize the counties by reducing the amount of state funding that goes to their general budgets.

“The current maintenance of effort requirement is completely illogical. It’s the school system that loses out in the end,” Israel said.

Counties that don’t spend as much on schools as the year prior are ineligible for an increase in state aid, Israel said. Montgomery County’s decision to undercut school funding would exclude the district from receiving $26 million in state funding in the upcoming fiscal year.

Not all counties receive an increase in state aid each year. Aid is tied to student enrollment rates. In counties like Talbot, where enrollment dropped, no additional state funding was awarded this year, giving county leaders less incentive to match state spending, Craig said.

Both state legislators and county leaders want changes in the maintenance of effort law. Legislators on the House Appropriations and House Ways and Means committee are expected to meet Friday to discuss changes to the current maintenance of effort law.

Del. Sheila Hixson, D-Silver Spring, chair of the House Ways and Means committee, said Friday’s meeting will provide legislators a chance to listen to all of the complaints and concerns around maintenance of effort. Representatives from county school boards, teacher unions and county associations are expected to be on hand.

“Nobody is going to say that they think maintenance of effort is perfect. There will certainly be disagreements about fixes and what the actual problems are,” Sanderson said.

Currently, the state Board of Education allows counties to apply for a one-year waiver that would allow them to avoid penalties if they don’t match state funding at the required level.

Waivers are usually granted for short periods of financial hardship. But, Sanderson said the waiver process does not account for the long-term financial struggles that counties now face. He wants counties to be granted longer-term waivers.

Meanwhile, state and county education advocates say there’s no incentive for counties to apply for waivers because they can simply ignore the law without penalty if they’re ineligible for an increase in state aid. The advocates want to close that loophole by imposing a penalty on the general county budget if education funding is reduced.

“Our sense is that there’s a lot of momentum to fix maintenance of effort. We have had intensifying conversations with state legislators and there seems to be recognition that the law needs to be fixed,” Israel said. “State education shouldn’t supplant local funding.”

Capital News Service reporter Mike Bock contributed to this story.