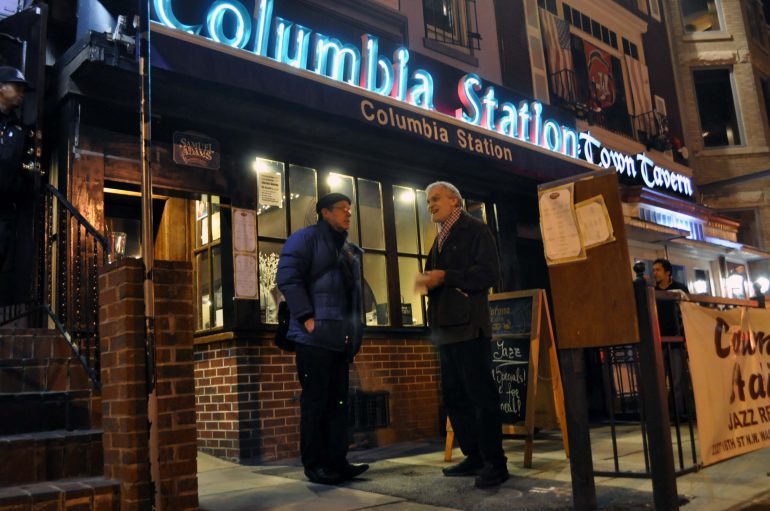

WASHINGTON — It’s late evening, and the sound of Miles Davis’ “Solar” drifts to the sidewalk from a small Adams Morgan club with open windows.

The pianist, Peter Edelman, has been a staple at this club, Columbia Station, for the past 12 years.

The music coming out of the piano is almost unbearably soulful, both electrifying and soothing. At the moment, he is playing to an empty house.

The surroundings are profane. The cushions on the barstools are torn. A malfunctioning security system chirps every six seconds. A large drop of water descends from the leaky ceiling.

Edelman does not do this kind of work for the audiences.

“Turnout isn’t where we’d like it,” Edelman says. “It’s not unusual for me to be playing to nobody for hours on nights like this. Jazz has fallen out of favor with the masses.”

Edelman limps over to the bar and orders a drink. He shares a laugh with the bartender about the constantly beeping security system. He comes off as both affable and somewhat world-weary.

He says a young, enthusiastic jazz audience is a rare find these days. Indeed, the setting of the club seems to underscore his point.

Columbia Station is wedged between nightclubs that plays house music and crowded, noisy sports bars. Virtually every other establishment on the street is replete with flashing strobe lights and booming subwoofers.

The insatiable bass beat from the techno club next door bleeds through the thin walls.

“Once you convince kids that some base pop music is art, then there’s no end to the drivel you can shove at them and they’ll buy it. Train a young person’s mind to have no artistic standards and you’ll have a customer who will buy cheaply made electronically synthesized music time after time,” Edelman says.

“It’s like McDonald’s food,” he says.

Jazz, on the other hand, is different, he says, and it is this difference that keeps him playing, despite the poor turnout.

Playing in the most powerful city in the world, he says jazz provides an analogy for the perfect form of government.

“It objectifies freedom and democracy. In jazz, you’re not straightjacketed by the status quo. There’s nobody dictating you what to do, like in a fascist system. You don’t have this freedom even in classical music. There, the dictator is the baton of the conductor,” he says. “Here, we’re free.”

Steve Furtado, a manager at the club, says watching him play is a unique experience.

“He’s a one of a kind guy,” Furtado says. “He brings an energy to his playing that the people seem to really like.”

Edelman cares less about popularity than he does about preserving jazz as an art form.

“Jazz simply is a superior form of music,” he says coolly. “The range of expression is limitless. And with jazz, there’s something that no other music has – on the spot, collaborative improvisation between multiple artists.”

He says there’s a spiritual aspect to performing.

“I do jazz because I want to be like God,” he says. “I get the sense that it’s the music God would want us to play because it’s truly limitless – truly infinite – like God.”

Edelman is a middle-aged man of generally disheveled appearance. His back is hunched and he walks with a pronounced limp.

He grew up in a very musical environment in his northern Virginia home. His father was a habitual, even compulsive, collector of jazz, with “an encyclopedic library” of jazz records. His mother was a classical pianist.

“I was absorbed into jazz more by osmosis than by choice,” he said.

When he was seven, he discovered a new favorite activity — banging on the family piano. He began lessons shortly thereafter.

He played piano through high school and college. He went to college in Texas for several years before returning to the district. He then got a job playing for the now defunct club One Step Down in the 1980s.

From there, he moved to another district club, Twins Jazz, and eventually came to Columbia Station. Along the way, he became acquainted with Wallace Roney and Butch Warren, two jazzmen of note, who helped him further his career.

These days, his trio plays for hours Friday through Sunday nights, sometimes to single digit crowds.

He’s uncertain about his future. Playing music for a living and paying his bills don’t seem very compatible, he says.

He doesn’t seem particularly anxious about anything, though.

The band wraps up its set with Charlie Parker’s frenzied tune “Anthropology.” Edelman thanks everyone for coming out as if the place is packed. He introduces each band member to light applause.

“And how about a round of applause for the most important member of our band, Phillip the Tip Jar, yes Phillip the Tip Jar. Thank you all for supporting local jazz.”

“Phillip the Tip Jar” is empty.

You must be logged in to post a comment.