ANNAPOLIS – Malcolm Franklin is a jockey in Maryland.

The life of a jockey is not easy. Schedules can be grueling and the pressure intense. Weight is constantly battled.

And there is something absurdly dangerous about a man intentionally making himself as light as possible, riding a 1,500-pound muscular animal, and fighting for position on a track filled with similarly starved men — atop similarly sinewy horses.

For one of Maryland’s only black jockeys life is even tougher.

“It can be hard and isolating,” Franklin, 22, from Orangeburg, S.C., said from inside the Laurel Park jockey’s locker room, known as “the jock’s room.”

A room, Franklin said, that on average is filled with 30 other sustenance-sacrificing jockeys all fighting for the same prize money.

“There’s definitely some jealousy and hate,” Franklin said.

There are a few who make racial comments, some under muddled breaths, some over raised voices, Franklin said.

But Franklin tries his best to move forward.

“I’ve learned to blow it off and not let it bother me too much,” he said, quickly pointing out he’s accepted by most.

But in a sport where death is merely a misstep away, the pursuit of prize money can breed dangerous maneuvers on the track.

In February, Franklin competed at West Virginia’s Hollywood Casino at Charlestown Races.

When his mount clipped hooves with another, both jockey and horse went faces first into the earth. Franklin was thrown about 10 feet.

“It’s best just to ball up,” he said.

He rolled perilously close to the paths of other riders, but emerged unscathed.

The fall, Franklin said, was the result of being hemmed in by traffic. Franklin said the maneuver was not intentional, but it also wasn’t the first time.

And at five-foot-six, 116 pounds, similar falls could easily end his career, if not his life.

“The No. 1 thing,” Franklin said, “is to stay healthy.”

He is healthy this season and off to what he calls the best start of his career. Currently, he is second among Laurel’s Winter Meet jockeys behind only his friend, British jockey Sheldon Russell.

When he first came to the U.S., Russell said Franklin took him in and helped him acclimate. The two even became roommates.

They seem more like brothers than jockeys, competing for purses and exchanging barbs, one with biting British wit, the other slinging southern drawl.

In fact, pleasantries didn’t fly until after Franklin left the room.

“It’s just nice to see a kid from humble beginnings doing good for himself,” Russell said.

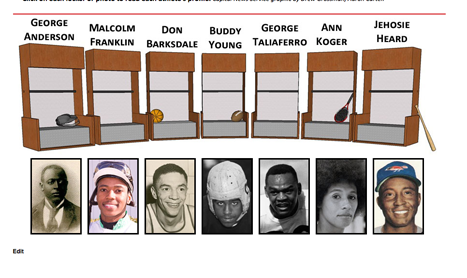

Now, each dreams of one day riding in the Preakness, the same race George “Spider” Anderson became the first black man to win in 1889.

Franklin said he doesn’t know much about Anderson, but understands his journey could not have been easy.

“He must have faced a lot of pressure, stress and painful stuff,” Franklin said.

For a chance at the Preakness, Franklin would accept it all. He has watched Maryland’s biggest race every year since he moved north.

“It brings a huge adrenaline rush just watching,” Franklin said.

All he wants is a chance, an opportunity to prove himself.

“Horse to horse I don’t think anyone can out ride me,” Franklin said.

The comment seemed less born from arrogance than the confidence that comes from starting at the bottom and slowly ascending through the ranks.

Franklin began cleaning out stalls at 11. His godfather, Eddie Moe Aiken, worked at the Elloree Training Center, a horse training facility in South Carolina.

Franklin’s mother, Patricia Starks, worked long hours, so Aiken and his wife, Ruth Aiken, helped by looking after Franklin.

Eventually, Franklin began riding, and at 14 won his first two races. By 16, he began racing at Colonial Downs in Virginia. And after completing his junior year of high school he started riding full time.

When he came to Maryland in 2007, leaving his family behind, he rode during the day and took classes at night.

He hopes his sacrifices will help him get mounts in bigger events.

Despite being just 116 pounds, Franklin describes himself as larger than most jockeys. He’s constantly concerned about his weight.

He eats just twice a day.

He tries to run two or three miles every other day, concerned about maintaining a high metabolism.

Often, his schedule consists of waking at 6:30 a.m. to talk with trainers and secure horses for the day’s races.

Then, he competes from 12:35 pm to 4:30 pm at Laurel Park. From there, he drives to Charlestown, W.Va., for a race at 10:30 pm.

After the race where he and his horse fell, sore and in pain, Franklin still had to make the drive back to Maryland.

And the next morning, he had to do it all again.

“You gotta have some heart to do it,” Franklin said.

You must be logged in to post a comment.