WASHINGTON — The congressional race in Maryland’s 6th District has this year become the most closely watched in the state, but some rural voters still worry they could become irrelevant as candidates vie for support in Montgomery County.

“Unfortunately, the new district lines divide communities all across the state, and the effect that it has is that rural Maryland is completely losing its voice,” said Delegate Neil Parrott, a Washington County Republican.

Incumbent Rep. Roscoe Bartlett has kept the 6th District in the Republican column since he first won the seat in 1992, but after last year’s redistricting process, half of its population now lives in suburban Montgomery County. Registered Democrats outnumber Republicans almost by a three-to-one margin there, which means the new district narrowly favors Democrat John Delaney.

While this year’s race has demolished fundraising records for both candidates, some Western Maryland Republicans appear to have resigned themselves to the fact that voters in Montgomery County will flip the district from red to blue — and that Delaney can win by focusing his efforts there.

“I don’t think (Delaney)’s taking it for granted, but it’s obvious with the redistricting that the race is probably going to be decided in Montgomery County. I can’t blame them,” said Delegate Wendell Beitzel, a Republican who represents Garrett and parts of Allegany counties. “The way I see it, the district was changed for one purpose: to kick out Roscoe Bartlett.”

Maryland voters will have the final say on the redistricting plan, which appears as Question 5 on the November ballot.

“If the map had stayed the way it was, we’d be seeing a lot more of the candidates running for the 6th District seat now,” said Parrott, who led the signature drive.

Bartlett, a Buckeystown resident, has drawn on support from rural communities to win 10 terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. His campaign declined to comment for this article.

Based on activity on the congressman’s Facebook and Twitter profiles, Bartlett has campaigned less than Delaney, a wealthy businessman whose Potomac home falls about 350 yards outside the district’s limits.

Should Delaney win on Nov. 6, Maryland law would not require him to move. Still, the Delaney campaign never worried its candidate would be branded as a carpetbagger, said Will McDonald, a spokesman for the Democrat.

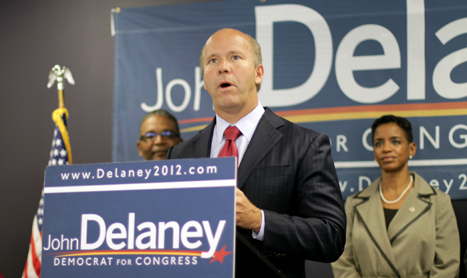

Delaney escaped a brutal primary election after Democrats clashed for the opportunity to face Bartlett in the redrawn district. Most of Maryland’s Democratic establishment, including Gov. Martin O’Malley, backed state Sen. Robert Garagiola, D-Montgomery, while Delaney landed the endorsement of former President Bill Clinton. Delaney also loaned more than $1.5 million to his own campaign, and ended up winning an outright majority on April 3, taking 54 percent of the vote to Garagiola’s 29 percent.

The combination of a well-funded opponent and a competitive district may have disheartened Republicans, but it has energized rural Democrats. To build support across the district, the Delaney campaign has tapped into a dormant volunteer base that hasn’t seen its candidate win since 1990, when Beverly Byron won a seventh term in the House.

“Nobody paid attention to us before because we didn’t have a candidate worth campaigning for,” said Stephan Moyland, president of the Garrett County Democratic Club. “The quality of the campaign is different with Mr. Delaney…. The organization seems to be stronger.”

Between the end of the primary and Oct. 16, the Delaney campaign recruited 1,754 volunteers who have knocked on doors and called supporters 371,189 times. About two-thirds of that grassroots operation has taken place in Montgomery County.

For campaign stops, however, the numbers are reversed. Of Delaney’s roughly 150 campaign events, more than 100 of them have taken place across northern and Western Maryland. And of the seven debates Bartlett and Delaney have agreed to attend, six will take place outside Montgomery County.

Before its lines were shuffled, the 6th District followed Maryland’s border with Pennsylvania into Baltimore County. O’Malley, along with Democrats in Annapolis, carved out the city of Frederick, but divided Republicans in northern Maryland between Reps. Andy Harris, John Sarbanes and Chris Van Hollen.

The Delaney campaign has sought to avoid the redistricting conflict by saying the responsibility lies with the Maryland legislature.

“John did not draw the lines,” McDonald said.

Another factor helping Democrats is Montgomery County’s diversity. The district’s racial makeup has shifted from 90 percent white in 2010 to about two-thirds today, as it includes more than 100,000 more minority residents. The 6th District now has the most Asian-Americans in the state, with about one in 10 residents identifying as such.

One of the arguments against the new district is that it has become too diverse, and that candidates have to represent the positions of both rural Marylanders and suburbanites — two groups of voters Parrott said share few beliefs.

“We both breathe,” but other than that, Parrott said, “we don’t have much in common with them at all.”

The 6th District was recently rated the ninth-least-compact in the country by Philadelphia-based mapping company Azavea, but Democrats said it has always consisted of a diverse group of voters.

“What did (rural voters) have in common with suburban voters in Harford County?” Moylan said. “Northern Harford County is a long way from Oakland, Maryland. Certainly Montgomery County is much closer.”

Even if voters reject the new districts, Democrats in Annapolis could find other ways to balance the population math without stripping the 6th District of most of its territory in Montgomery County. And the changes — if any — wouldn’t go into effect until the 2014 elections.

“The thing is, it doesn’t matter how the ballot issue comes out,” Beitzel said. “If the voters decide to overturn the law that created the districts, whoever gets elected is still going to represent us for the next two years.”