MILFORD, Del. – Starting at 6:30 a.m., five days a week, Ray Ellis sends out a small crew from his local farm in Millsboro, Del., to perform one unique and smelly task: piling up and collecting tons and tons of chicken litter from area farms, to sell.

“It’s a pretty good business,” Ellis said. “We go to Delaware, Maryland, basically all over the peninsula.”

Chicken litter is valued by many crop farmers in Delaware and along Maryland’s Eastern Shore for its use as a nutrient-filled fertilizer, and poultry growers in the area often have excess litter from their chickens. Ellis took advantage of that supply and demand and turned it into a business, taking excess chicken litter from growers and selling it to local crop farmers.

But now, he fears that business could fall apart as Maryland prepares to implement new regulations on phosphorus in the soil.

Those new regulations come in the form of the Phosphorus Management Tool, a set of measurements and equations developed by the University of Maryland to rate the potential for phosphorus runoff in soil.

The new tool will only apply to farms with a Fertility Index Value of 150 or more, meaning they already have excessive nutrients in their soil. The tool will take a more comprehensive look at how much phosphorus is in the soil and the chance that it could run off and end up in a watershed.

Depending on how farms rate with the new tool, they could be more restricted in how much phosphorus they can add in the future, with “high risk” farms forbidden from adding any more of the nutrient until their levels are in check. Maryland is having public meetings on the new regulations now, but the tool is set to go into effect Jan. 1, 2015.

To understand how regulating just one particular chemical could affect a farmer specializing in the business of buying and selling chicken litter, it’s necessary to look at how Ellis’ business works and how large it really is.

“When their chicken comes out, we come in, get their litter, clean out the coop, and we do that for around 780 houses,” Ellis said.

Ellis said he and his team clean out those coops for free, and in exchange for the service, the farmers let him keep their chicken litter. The crew then sells the litter to crop growers close by, who use it as an organic fertilizer.

Often, Ellis’ team moves the manure only 10 or 20 miles, from one town on the Eastern Shore to the next. Ellis said the team moves about 200,000 tons of chicken waste every year.

“We sell it, on average, for about $18 a ton,” Ellis said.”So it’s got some real value to it.”

But farmers – especially those in the lower part of the Eastern Shore – are worried that with the new phosphorus regulations in place, they won’t be allowed to use high-phosphorus chicken manure as a fertilizer any more.

If farmers can’t use manure as fertilizer, Ellis said, demand for the chicken litter will decrease. If that happens, Ellis fears he could lose his customers and be left with loads of chicken waste and no one to buy it.

“I’m concerned about my business,” Ellis said. “I’m concerned about the Eastern Shore.”

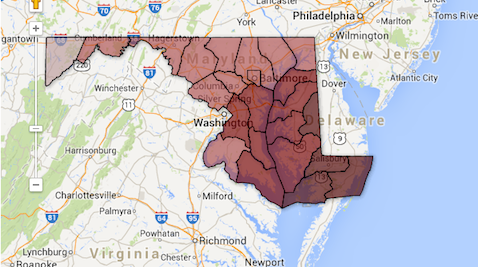

From the state’s perspective, the new phosphorus regulations are necessary to limit and better determine the amount of phosphorus entering the Chesapeake Bay. Soil tests bear that out, as a 2010 study from the Environmental Working Group showed that in places like Somerset and Worcester counties along the Lower Shore, over 75 percent of the soil tested was found to have excessive phosphorus levels, meaning it had more phosphorus than what’s needed for crop farming.

Doug Myers, a senior scientist with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, said phosphorus from manure, combined with other nutrient runoff from places like wastewater treatment plants, has had serious effects on the bay’s biology.

Myers said the problem comes from algae, which feed on the excess phosphorus and use up much of the dissolved oxygen in the water. That leads to “dead zones” – areas in the bay with so little oxygen that fish and other animals can’t live in them.

“This is why phosphate was banned from detergents across the country many years ago,” Myers said. “Because discharges would get into lakes and create these algae blooms and lead to dissolved oxygen problems and dead zones.”

Myers said those dead zones peaked a few years ago, but due to conservation efforts from the state and other organizations, they’ve begun to decline.

Scientists say that decline could speed up even more if farmers switch from chicken litter to chemical fertilizers, as chemical fertilizers allow farmers to decide exactly how much phosphorus they’re putting into the soil.

“Chicken litter has a certain chemical analysis,” said Frank Coale, a professor and agricultural nutrient management specialist at the University of Maryland. “You’re talking about a certain amount of phosphorus and nitrogen per ton. And the farmer can’t manipulate that. But a farmer can call up a fertilizer dealer and ask for a fertilizer with a prescribed amount of those nutrients. So there’s a whole lot more flexibility with purchased fertilizer, but not with manure.”

But there’s also a downside to a switch from manure to chemical: new expenses for farmers.

Bill Satterfield, the executive director of Delmarva Poultry Industry, Inc., said swapping out manure fertilizers for chemicals won’t come cheap for crop growers in the region.

“Some farmers who have been using chicken manure exclusively will now use commercial fertilizer. So that’s a new cost,” Satterfield said. “And added on to that, they’ll have to pay for new equipment to spread out that chemical fertilizer, too. It will just create a lot of problems for farmers.”

State officials acknowledge that farmers will have to make concessions with the new phosphorus regulations, but they say there will continue to be a market for chicken litter in the future.

“One of the things that’s particularly valuable is that this material does have value,” said Royden Powell, assistant secretary of resource conservation for the Maryland Department of Agriculture. Powell said that while the lower Eastern Shore may not use chicken litter as much as it has in the past, other parts of the state, like the upper parts of the Eastern Shore and the Western Shore, would still want the material.

“Historically, litter has moved to the Western Shore,” Powell said. “There are farmers there that are actively seeking this material. So it’s in no way limited to the Eastern Shore. And that’s going to hold into the future.”

To ease that transition, the state is revitalizing its Manure Matching Service, a program to connect livestock farmers who have extra chicken litter with other farmers across the state in need of manure. Powell said if the program is successful, it should ease the burden on farmers, creating a new, more spread-out marketplace allowing growers to sell their manure and use that money to buy chemical fertilizers.

But Ellis, the manure transporter, said even if the demand for chicken litter stays high in new parts of the state, his business still won’t be able to handle it due to the longer travel time. Ellis said most of his business is done relatively locally, so to suddenly expand that to large distances doesn’t make sense.

“Even if you had enough people on the Western Shore who want it, the logistics don’t work. We’d have go 10 times as far to truck it, so the cost goes up. The logistics don’t work,” Ellis said. “If a truck can haul six or seven loads a day locally, versus one to the Western Shore, it’s less money. It ain’t rocket science.”

One idea that both farmers and the state see as a potential solution is power plants that convert chicken litter to energy. Maryland has signed a contract with a developer to create such a plant in Caroline County, and the state is working on developing a similar plant to help power the Eastern Shore Correctional Institute.

Those projects are still in their early stages, but Agriculture Assistant Secretary Powell said the state is working hard to make sure they’re a part of Maryland’s energy future.

You must be logged in to post a comment.