COLLEGE PARK – The paper on one of the drone laboratory’s doors has scrawled on it: “Bug Laboratory (Enter at Your Own Risk).”

Inside the University of Maryland’s Autonomous Vehicle Laboratory is an unusual combination of insects, drones, and drones that look like insects.

Scientists across the country are turning to insects to create smaller robotics. The research could shape the way government responds to natural disasters, and even how we receive packages.

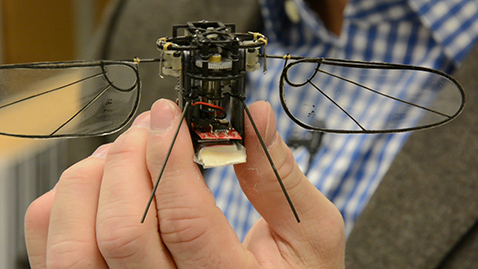

Using elements such as sensors inspired by an insect’s vision and a flapping-wing flight system, the vehicles are combining nature and mechanics.

“Typically, what we see in biology is the exact opposite of what we see in engineering systems,” said Sean Humbert, a professor of aerospace engineering and the director of the program.

The Harvard Microrobotics Lab is also looking to insects for inspiration. It’s best known for its microbee, a flying robot about the size of a penny.

“The key reason is that biology solves problems in a different way, specifically through evolution,” said Yigit Menguc, a post-doctoral candidate at the Harvard lab.

Through time, evolution has found solutions to problems scientists still struggle with when building small robotics.

“It’s hard to make robotics at the same scale as insects, so one of the problems is how do you build them? But also at that level the physics change,” Menguc said.

Stabilization and control are two of the challenges the Maryland laboratory is working on.

“We’re trying to understand why nature has found and is using that solution, and we’re trying to understand the benefits of that and whether or not we can scale that down to systems of that size,” Humbert said.

Insects are robust when reacting to turbulence and environmental disturbances, and trying to mimic the way they respond to things such as gusts of wind could help robots with their stabilization and control problems.

Although vehicles on the ground have fewer of these problems, the lab is still looking to improve their efficiency to do things such as perch on walls and ceilings.

“Not just things that fly, but things that crawl, as well as things that swim. So we’re interested in all aspects of the sensory feedback systems and the processing capabilities of animals,” Humbert said.

The project is receiving funding from the Air Force, Army, Navy, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and NASA.

Minuscule drones that are able to navigate by themselves can be used in disaster site exploration, military operations and cluttered urban environments.

“Effectively, you could let one of these tiny vehicles go, something like the size of a hummingbird or less, in a cluttered building environment and it could navigate its way through the building without running into things and potentially collect information from the environment,” said Greg Gremillion, one of the doctoral students working on the project at Maryland.

The lab’s prototypes include a flapping wing vehicle the size of a hummingbird and a larger vehicle developed primarily by Gremillion and doctoral student Hector Escobar that uses a sensor ring modeled on an insect’s vision.

An example of how future prototypes of these vehicles could be used is after a natural disaster, to navigate around areas that are too small or unsafe for humans to gather information and video.

Another drone being developed by Escobar uses a combination of sonar and infrared technology to help navigate in dark areas.

This type of drone would make a firefighter’s job safer. Instead of sending firefighters into a burning building to ensure it’s been evacuated, a drone would be sent into the building.

The drone would be able to navigate the building as well as send information back to the firefighters about what’s in the building.

Outside of government and disaster-site exploration, the technology being developed at the drone lab could have commercial implications as well.

The example that Humbert gave is how Amazon is developing a drone delivery service.

These drones would not be able to rely on GPS alone to deliver packages. They would also have to avoid moving objects and other barriers such as wires, birds and even children.

Although the research and projects are futuristic, scientists still remember that it was nature that brought them here.

“It would be nice to see this used to promote conservation. As we lose these examples in nature, we lose these examples for innovation,” Menguc said.