ANNAPOLIS — Kerry Palakanis has spent most of her career as a nurse practitioner working in rural communities.

In Somerset County, where she owns and operates the Crisfield Clinic, she comes face to face with the everyday challenges of providing health care in a rural area.

“The patients are very sick, and the resources are very scarce,” Palakanis said.

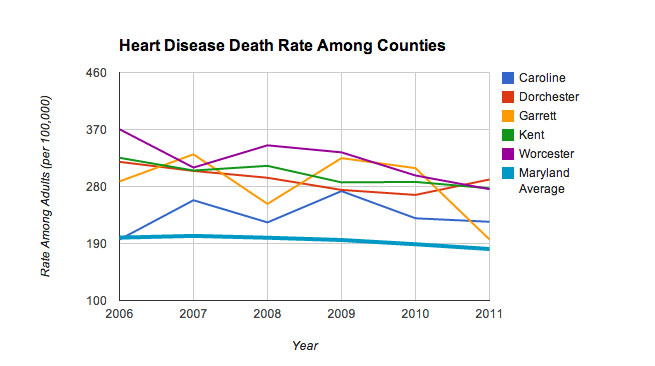

A lack of health care providers in Somerset County and other rural areas around Maryland is contributing to health disparities that include higher rates of heart disease and obesity and lower life expectancy rates.

“The other way I describe it … is we’re akin to a Third World country,” Palakanis said. “When I see people going off to foreign countries to help with health care, I think, ‘Why not come to Somerset County?’ We have all the same issues here. You don’t even need a passport.”

In the national 2014 County Health Rankings released by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, five of the 10 least healthy jurisdictions in Maryland are considered partially or completely rural by federal standards. Three others in the bottom 10 — Allegany, Cecil and Wicomico counties — fall under the state’s broader definition of rural.

The annual rankings, released in March, are based on health outcomes that incorporate the length and quality of life for residents of each jurisdiction.

In rural Caroline County, which ranks second-to-last in health outcomes, ahead of only Baltimore City, life expectancy is seven years shorter than in top-ranked suburban Montgomery County, according to the most recent Maryland Vital Statistics Annual Report, released by the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene in 2012.

Rural health experts and advocates link the disparities to the scarcity of health care providers in rural areas and the decreased access to care that is a result.

The ratio of primary care providers to residents in Caroline County is 1-to-2,915, according to the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. That ratio, the worst in the state, amounts to just 11 primary care providers for the entire county.

Maryland as whole has one primary care provider for every 1,647 residents.

While rural Talbot County boasts the best ratio, with 35 primary care providers lending the jurisdiction a rate of 1-to-1,056, six of the 10 worst ratios belong to federally designated rural counties. Caroline, Somerset, Dorchester and Garrett counties — all rural — hold the bottom four spots.

As a result, people living in rural areas often have to travel long distances for health care,

a disincentive to getting even the basic preventative care they should be receiving, according to Dr. Claudia Baquet, an associate dean at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the director of the school’s Center for Health Disparities.

The rate of speciality care providers in rural areas throughout the state is often worse, and Palakanis regularly sees the effects of that in her clinic.

Palakanis said the clinic can fit in anyone who is willing to come for primary care, but if they need speciality care, she has to send them to Salisbury, where she said resources are “overstretched at best,” or Baltimore, which is almost three hours away.

And in a county like Somerset, where poverty and unemployment rates are high, getting patients to take a day off work to seek health care can be challenging.

“For my patients to get to Baltimore, it would be just as easy for me to say, ‘I’m going to send you to the moon,’” Palakanis said.

For years, rural health advocates looking to bridge the gap between rural populations and the hubs of medical resources in urban and suburban areas have focused on the expansion of telemedicine, which allows patients to connect with health care providers and specialists through an Internet platform like Skype. Supporters say telemedicine encourages people to seek care and follow-up consultations they might otherwise neglect.

But much of the campaign for improved rural health centers around efforts to recruit and retain health care providers to practice in rural communities.

The workforce shortage in rural areas is the biggest barrier to care, said Michelle Clark, executive director of the Maryland Rural Health Association. She said she expects the issue to “bubble up to the forefront” soon with the implementation of the Affordable Care Act.

“We know the people who had insurance before we expanded our insurance pool couldn’t [easily] find access to care,” she said. “Now you have a greater number of insured who are going to be looking to access the health care delivery system for the first time.”

The surge of newly insured Marylanders will likely lead to increased demand in rural areas where the market is already stretched thin, and some advocates believe that aggressive campaigns will be necessary to educate residents on how to best utilize the health care options available to them.

“Having insurance is not the only thing that’s needed to have access to care,” Baquet said. “You have to have the providers, the physicians, the nurse practitioners. You have to have the facilities.”

Rural health experts have been pushing to expand programs that offer incentives to providers to practice in underserved areas.

They say incentive programs are critical because of the level of debt that students emerge from medical school with — roughly $160,000 on average, according to Dr. Milford Foxwell, associate dean for admissions at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

In an effort to pull themselves out of debt as quickly as possible, many medical school graduates choose to practice in urban areas, which generally have better reimbursement rates. They are also drawn to fields other than primary care, which tends to pay less than certain subspecialty areas.

In Maryland, the Loan Assistance Repayment Program awards up to $30,000 to graduates who agree to practice in underserved areas.

But rural health advocates say the reach of that program and others like it is limited by the federal standards that determine which areas qualify as rural.

Clark said that Maryland’s competition for federal funds suffers because the state as a whole doesn’t seem rural compared to others and because it has no overall shortage of doctors in Maryland — the providers are just clustered in urban areas.

Another serious impediment to recruiting medical school graduates to work in Maryland’s rural areas is the lack of residency programs there.

Jake Frego, executive director of the Eastern Shore Area Health Education Center, said national data shows that about half of all physicians choose to practice within a 50-mile radius of where they do their residency.

“So out of the pool of docs who … graduate to residency, automatically about 50 percent we lose because of [the] absence of a residency program,” Frego said.

Area Health Education Centers like the one Frego runs are dedicated to recruiting and retaining health care professionals to work in underserved areas. Initiatives like the center’s Clinical Education Program expose students, many of whom are from urban areas, to what it’s like to practice and live in a rural area.

Palakanis said the interns that come to work for her in Crisfield learn very quickly about the challenges of rural health. But Palakanis sees the rewards in that.

“I find the population to be interesting, and always a challenge,” she said with a laugh.

“You have to learn to do a lot with little.”