ANNAPOLIS – The $225 million the state has set aside to build three new jails for juvenile delinquents and improve a fourth in Maryland should be spent on community-based treatment instead, a review panel found.

Putting more money into juvenile jails would lead to less effective treatments, according to a report by the Maryland Juvenile Justice Monitoring Unit, which tracks the needs of children under the Department of Juvenile Services and produces quarterly reports on the conditions of the department’s facilities.

The budgeted money, which includes the proposed construction of three new juvenile jails in Baltimore, Prince George’s County and Wicomico County, should be re-directed to provide more nonresidential, evidence-based treatment programs in the communities, said Nick Moroney, director of the Maryland Juvenile Justice Monitoring Unit.

More emphasis on community-based treatment could help reduce juvenile recidivism rates, according to the report.

(See it here: http://www.oag.state.md.us/jjmu/reports/14_Quarter2.pdf )

“Maryland should follow the national trends and be moving away from large, congregative facilities and move more towards services in the community,” Moroney said.

Not all juvenile offenders are suited for community-based treatment, and some, who are very high risk or have certain mental health needs, need to be incarcerated out of state because Maryland lacks the specific services to treat them, said Eric Solomon, public information officer for the Department of Juvenile Services.

Last year, 126 youth were incarcerated out of state, according to the department’s data resource guide. The construction of the proposed facilities could mean that more youth are able to stay in state in the future, Solomon said.

“We would love to be serving as many kids as we can in state,” Solomon said. “Some of these possible treatment centers that we could be building could help us in bringing back some of those kids to treat here.”

Maryland has seven state-operated facilities for convicted youth offenders, including five lower-level security facilities controlled mainly by staff, and two that are heavily secured by hardware such as fences and bars, according to the Department of Juvenile Services.

In 2013, 630 youths were placed in staff and hardware secure facilities and 716 were in community-based treatment in Maryland, according to the Department of Juvenile Services.

Studies have shown that intensive, community-based treatment programs, such as multisystemic therapy and functional family therapy, are more successful at reducing recidivism among juveniles than incarceration, according to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, a Baltimore-based philanthropy working on national children’s issues.

Functional family therapy involves the youth’s family members and aims to turn around juveniles who are at risk or already exhibiting delinquency, substance abuse or behavioral issues without sending the child away from home. Multisystemic therapy is designed to work with chronic and more serious juvenile offenders in their own communities to address every aspect of their lives, from their families and friends to schools and neighborhoods.

But their success rates vary: One is better than incarceration, and the other worse, research indicates.

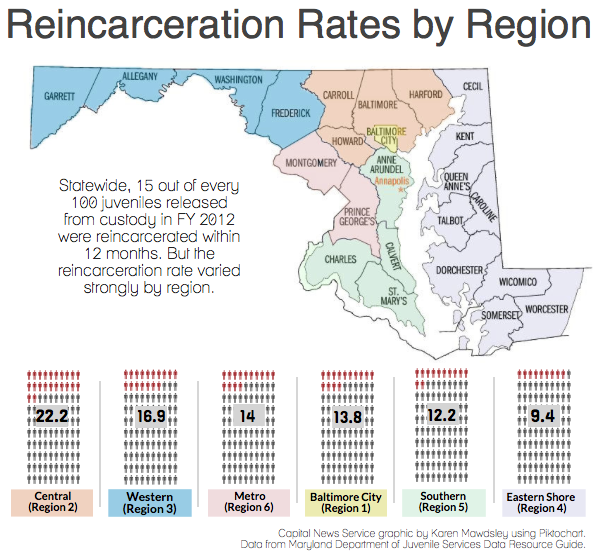

More than 19 percent of youth were reconvicted and 14.7 percent were re-incarcerated 12 months after release from a state-operated facility, according to the Maryland Department of Juvenile Services’ 2013 data resource guide.

More successfully, 12 percent of Maryland youth were reconvicted and 7 percent were incarcerated within 12 months of completion of functional family therapy in 2012, according to a 2013 report from the University of Maryland Baltimore County. Twenty-seven percent of youth were reconvicted and 19 percent were incarcerated in 2012 within 12 months of completing a multisystemic therapy program in Maryland, according to a similar report.

The statistics did show that functional family therapy produced lower rates of recidivism among youth offenders than incarceration and multisystemic therapy produced higher rates, but it’s impossible to fairly compare these rates because of the many variables at play, said Jennifer Mettrick, director of implementation services at the University of Maryland Baltimore County.

How a child responds to community-based therapy depends on the kind of offender he or she is and whether he or she has been through the justice system before, and there is no concrete system to decide who gets what kind of treatment, Mettrick explained.

“You can’t do a straight comparison because there’s not a systematic way that kids are being referred to these services verses out of home,” she said.

There are sets of criteria that make youth ineligible for community-based treatment, such as exhibiting suicidal, homicidal or psychotic behavior, being charged as a sex offender or not being of the appropriate age. Youth must be 10-18 years old for functional family therapy and 12-17 years old for multisystemic therapy. Once a youth’s eligibility for community-based treatment is determined, it is up to the court to decide where he or she is sent.

Sometimes, the decision comes down to wherever there is availability. This means that less serious offenders can wind up in residential facilities, while more serious offenders are being treated in their communities, Mettrick said.

“Sometimes they’re an apples to apples comparison, sometimes they’re not,” she said. “But there are a lot of very similar kids that just by chance happen to get into one or the other service.”

Treating children in the community is much cheaper than treating them in a residential facility. The average cost per child per day for multisystemic therapy is $110, compared to $34 per child for functional family therapy, while each day at a state-operated facility per child costs $274 or $531, depending on the security level of the facility, according to the university’s report.

“If we can keep 50 percent of kids from coming back into the system, and we’re doing it at a much reduced cost and a much smaller length of time and kids are able to stay in their communities, that’s a win-win,” Mettrick said.