WASHINGTON – New Hampshire realtor Rocky Lagno knows from cancer.

Twenty years ago, his wife’s mother died of breast cancer. He lost his own mother to ovarian and stomach cancer a few years ago. And in 2011, Lagno himself was diagnosed with lung cancer, even though he’s not a smoker.

Lagno now takes two pills daily in order to stay alive.

That is why he and his wife Geralynn Lagno recently joined more than 300 researchers, clinicians, patients and survivors to lobby Congress for more cancer research funding.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH), made up of 27 institutes and centers, is where the bulk of fundamental medical science takes place, providing for a variety of breakthroughs in cancer research. NIH is overwhelmingly funded by the federal government, but Washington’s budget cuts in recent years are starting to take their toll, researchers and others say, slowing the growth of NIH’s budget and curtailing important cancer research.

Less funding translates into fewer investigators taking risks doing innovative research. And less research means fewer lives saved in the long run.

In a recent speech in front of members of Congress, NIH Director Francis Collins drew attention to the latest reports by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Association for Cancer Research. The reports told a worrisome story of the country’s ability to keep up with cutting-edge research.

“When young scientists approach (NIH) with their bright ideas, traditionally it has been one chance in three that their application will be supported. That has been the case in the last half a century,” said Collins. “Since 2003, as we progressively lost more than 20 percent of our purchasing power, the success rate has fallen to 16 percent. Effectively, it means we are leaving half the great science on the table because we can’t figure out the way to pay for it in the current circumstance.”

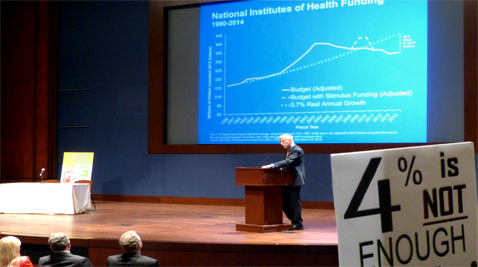

On average, for the past several decades, NIH’s budget consistently grew at about 3.7 percent a year, including adjustments for inflation. The trajectory was even better when Congress doubled appropriations starting in 1998 – creating double-digit growth for five consecutive years.

The growth began to slow after 2003. The agency saw its first budget decline in 2006. And in FY 2013 – when sequestration became a reality – the agency’s budget was reduced by about $1.5 billion, 5 percent below FY 2012.

The downward trend has led to a greater than 20 percent loss of the agency’s purchasing power. A 7.5 percent budget increase last year has helped, but not significantly made up for the previous losses, especially when inflation is taken into account.

For patients like Lagno, the situation could mean a lack of life-saving drugs.

“Recently FDA approved five new targeted cancer drugs. The reason why we had not done more was because funding was limited. There are a number of ideas and drugs but we had to be selective due to the reduction in funding,” said Carlos Arteaga, president of the American Association for Cancer Research, during an interview at the cancer rally on Capitol Hill.

As science has come a long way to develop effective treatments, the cancer mortality rate has been significantly declining. But time does and will remain a serious determinant in the cancer game. With research and development costs running as high as $1 billion for certain investigations, it can take up to 10-15 years to develop a drug that targets a specific type of cancer with a relatively small market.

Even so, the resulting treatment can be so individualized that one drug may work on one person and fail on another. Lagno is taking a second-generation drug (a previous one approved by the FDA a year ago did not help) named ceritinib, approved in April and on which researchers worked for a number of years, including clinical trials.

Speaking at the 5th Annual Pediatric Cancer Summit hosted by the Congressional Childhood Cancer Caucus, Collins said the issue was not about doubling the budget, but the need for a stable and predictable trajectory of funding.

“Staying on that trajectory would provide much needed stability and we would be $10 billion above from where we are right now. Stable funding is needed to encourage investigators to undertake risks associated with new research. That would re-energize the community,” said Collins.

Sustainable funding for the years of investigation and clinical trials is also important because private pharmaceutical companies – such as Novartis, which funded the studies and developed Lagno’s ceritinib – cannot always afford investing hundreds of millions of stakeholders’ money in an activity that is not connected with the final product.

“Cures start with research, and I’m proud of the advances NIH has made in understanding, diagnosing, and treating cancer,” said Rep. Chris Van Hollen, D-Kensington, and a co-chairman of the Congressional Childhood Cancer Caucus. “We must do everything we can to ensure that we robustly fund NIH and stop the indiscriminate sequester, which has had a real and negative impact on progress fighting cancer.”

It remains to be seen how Congress and the White House will eventually respond to the arguments for more funding. In the meantime, Lagno said that after meeting with two senators and two representatives in September, he was surprised how receptive they were to the idea of increasing the NIH budget.

“They sounded optimistic about bringing funding to the level that would account for the inflation over the course of several consecutive years and even adding adequate cost of living adjustments,” Lagno said.