WASHINGTON — The words “depression” and “suicide” may immediately bring to mind the image of a young boy or girl feeling like a failure and thinking there would be solace in death, but we may be wrong.

Recent data shows that suicide rates among middle-aged people was the highest compared to all other age groups.

And experts warn that public awareness about the warning signs of suicide continue to be abysmally low.

The highest rate of suicide was among people aged between 45 and 64 years: roughly 19 in every 100,000, according to 2013 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The second leading group of people who committed suicide was those aged 85 years or older, with a rate of 18.6 per 100,000; those aged 15-24 years old ranked third with a rate of 10.9 suicides per 100,000.

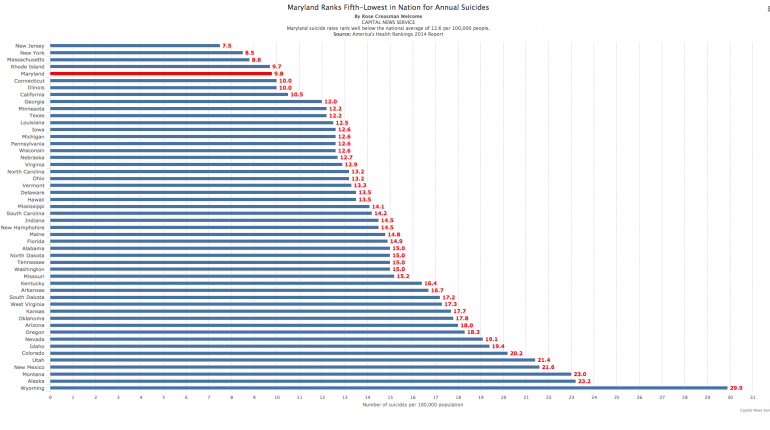

Suicide was among the top 10 leading causes of death in the country in 2013. Maryland has a suicide rate of 9.8 per 100,000, which is lower than the national figure of 12.6 per 100,000, but suicide is the 11th leading cause of death in the state, according to the CDC.

Experts said that a uniform cause of suicide among all age groups was depression.

“Two out of every three people who die by suicide were clinically depressed at the time of the suicide,” said Brandon Johnson, state coordinator of suicide and violence prevention for Maryland’s Behavioral Health Administration.

Julie Goldstein Grumet, director of prevention and practice at the Suicide Prevention Resource Center in Washington, said that there were very few suicide prevention programs aimed at middle-aged men. “Things are starting to crop up to target this demographic and we are very much at that early side,” she said.

She said that some groups have started to reach out to places where people work.

Johnson said that veteran suicides were a big contributor to the overall suicide rate among middle-aged or older people.

Johnson said that a lot of veterans may fall in the age range of 45 to 64 years and maybe dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. “They may not have the coping mechanisms to deal with that and maybe it produces some issues there,” he said.

Dr. Holly Wilcox, associate professor in the department of child and adolescent psychiatry at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, Baltimore, said that older people were harder to reach out to compared to younger people and may not receive the care and intervention they really need.

“Younger populations can be more readily identified in community settings, such as in schools and universities, by pediatricians, and in emergency room settings. Middle aged populations can be harder to reach for systematic suicide prevention approaches as they might not routinely see a primary care doctor,” she explained.

Unemployed people in middle age are also classified as “at risk.”

Dr. Niharika Khanna, associate professor of family and community medicine, pediatrics and psychiatry at University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, said that middle-aged people mask their depression and don’t reach out for help.

“It’s a little bit of a stigma against mental disease that leads people to believe that their condition is hopeless,” she said.

September is National Suicide Prevention month and experts stressed the need to identify warning signs indicating that a person is considering taking his or her life.

Johnson said that the signs could include indications that a person feels worthless, or someone articulating that their current state of life won’t change.

An important verbal cue is increased talk about death or dying. When a person becomes withdrawn or isolated and loses desire for any type of social interaction, it is another behavioral cue, Johnson said.

“So, if a person begins to say things like ‘You will be better off without me,’ things like ‘I wish I could just disappear,’ these are some signs,” he added.

Asking a person about suicidal thoughts does not aggravate suicidal tendency, Johnson said. “That is a myth, that is not true.”

“Being direct in questioning helps. So you can ask the person you know: ‘Are you planning to kill yourself?,’ ‘Have you thought about killing yourself?,’” he said.

When you reach out to a person, you show them that you care and that they can talk to you about what’s bothering them, Johnson said.

Wilcox suggested that a comprehensive and coordinated approach would be most effective in suicide prevention.

“Screening for suicide risk in emergency departments is also another important intervention. Restricting access to guns and other lethal means of suicide is essential,” she said.

Therapeutic treatments and medications have also been effective, she said.

“All of society – family, friends, teachers colleagues – it’s everyone’s responsibility to be caring of those around you,” Khanna said. “Even if it is the most supportive family, you may still be depressed. Having depression should be treated like a disease and not as a weakness.”

Grumet added that data suggesting higher suicide rates may reflect better reporting by doctors, hospitals and local and state agencies.

She said that families are now more willing to admit that a loved one took his or her life. “Sometimes medical examiners are reluctant to call something a suicide to protect the family and other reasons,” she said.