WASHINGTON – The Syrian refugee crisis has Maryland programs preparing for future newcomers, although few state residents know that such help exists, according to Baltimore City Community College Refugee Youth Project coordinator Kursten Pickup.

The project, aimed at providing educational and transitional assistance to youth refugees, says 650 to 750 refugees come to Baltimore each year. About 35 percent of them are youths.

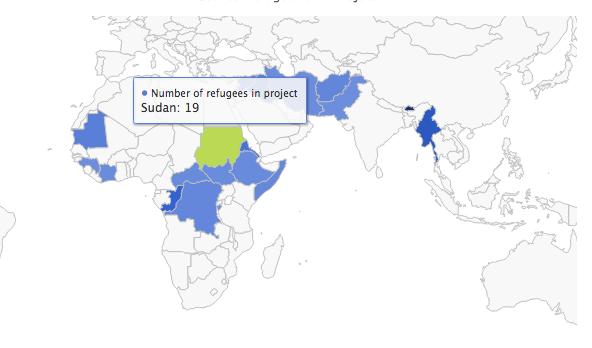

Many children in the program originate from Burma and Bhutan, according to Pickup. These refugees came to the U.S. to escape various kinds of persecution in their home countries.

The Department of State limits the number of refugees into the U.S. each year, depending upon each situation in the countries of origin, according to Ann Flagg, deputy executive director and family investment administrator for the Maryland Department of Human Resources.

According to the most recent figures, 1,242 refugees entered Maryland in 2013.

Last year, the State Department proposed increases in Syrian resettlement in a report to Congress. Now agencies such as the Maryland Office for Refugees and Asylees Services for Clients, a division of the Maryland Department of Human Resources, are tweaking current programs to anticipate the needs of Syrian arrivals.

“National slots have increased in favor of Syrian resettlement,” Flagg said. “We have been preparing because we already knew. Due to administration concerns and logistics at the federal level, we haven’t seen a [large] number of Syrians, but it will probably change.”

With limited money and staffing, the project looks for volunteers to mentor the young people.

“We have about 300 youth in the program,” Pickup said. “We just don’t have enough resources to serve the kids.”

To build community involvement and knowledge, the project created art activities, such as murals, with other school children. Pickup attributes initial transitional struggles among refugees to language difficulties, bullying, discrimination, cultural differences and more.

“At the end of long-term projects, that is when more positive change takes place,” Pickup said. “They are getting to know the background of their peers.”

Although these projects create bonds for youth refugees and their peers, adults within the state are disconnected, according to Pickup.

“When we talk about our work, people are surprised about the amount [of refugees] living in Baltimore,” Pickup said. “Neighbors are aware, but might not know their actual status.”

Most current adult and youth refugees come to the country after years of waiting. However, recent traumatic events will still be in the minds of incoming Syrian refugees, causing concerns about their emotional and mental health, according to Flagg.

When refugees arrive in the state, the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene conducts a mental health evaluation.

“It’s not uncommon for refugees to be in camps for years,” Flagg said. “It takes time to determine there are no other options available. This is completely differently with Syrians.”

As current and future world refugees enter the program, Pickup’s organization, the state of Maryland and other partners plan to continue accommodating the youth and their mental needs.

“It’s not that they aren’t prepared,” Flagg said. “We just have to inform our program [partners].”