WASHINGTON –– A promising athlete and a sociable high school freshman, Kyle Smith was just one of the guys.

But one ill-fated decision was all it took to send the then-15-year-old from Harford County spiraling into psychosis.

Never to take his senior photos, never to pick out a tuxedo for prom, never to walk across the stage and receive his diploma – Kyle was no longer just one of the guys.

Smith has been hospitalized 44 times, attempted suicide 10 times — including two near-fatal attempts — and has undergone 28 electric shock therapy procedures in the five years since he bought his first pack of “spice.”

“The end result is,” said Smith’s mother, Robin, “I have a semi-functioning 20-year-old son who doesn’t have a reason to live.”

The teenager could count on one hand how many times he had smoked synthetic cannabinoids — a cheap, lab-produced chemical concoction sprayed onto a blend of herbs meant to mimic the effects of a marijuana high.

The American Association of Poison Control Centers, though, can count more than 6,000 calls from people nationwide who have been exposed to the psychoactive drug this year. And that number is on the rise.

In fact, calls to the centers’ facilities surged 38 percent from 2013 to 2014. Through Sept. 30 of this year, calls spiked 71 percent over the same period last year.

During that same time span this year, Maryland and Washington’s poison control centers received 241 and 53 calls, respectively. Even with a population that is more than triple Maryland’s, Florida has received 54 fewer calls. While the data illustrates the very apparent rise in synthetic drug use, the numbers do not necessarily convey the severity of cases for each state due to wide variations in methods of reporting.

“What gets reported to places like poison centers are instances when something bad has happened,” said Bruce Anderson, director of operations at the Maryland Poison Center.

“Unfortunately, it seems the stories that we hear are sometimes people using what they expect to be a therapeutic amount for them — you know, they are just trying to get high,” he added.

But the misconception that this mind-altering drug can give users like Kyle a “therapeutic” high is just as poisonous as the drug itself, experts warn.

Contrary to its name, synthetic cannabinoids — sold under the street names spice and K2 — share few similarities with the average marijuana leaf.

For one, they are created in labs, most located in China, according to Karl Colder, special agent in charge of the Drug Enforcement Agency’s Washington Field Division.

In these labs, chemists are staying at least one step ahead of drug enforcement officials in order to ensure these products are on the shelves. Overseas chemists, who are the main source for these synthetics, are constantly creating new iterations of the drug faster than the DEA can ban them

“To the best of our knowledge, it is in a powdered form when it is shipped,” Colder said.

“What ends up happening, for instance, is if you have a processing site here in the United States, they will mix it with acetone — kind of the same thing as paint remover or fingernail polish remover — to liquefy (it),” he explained.

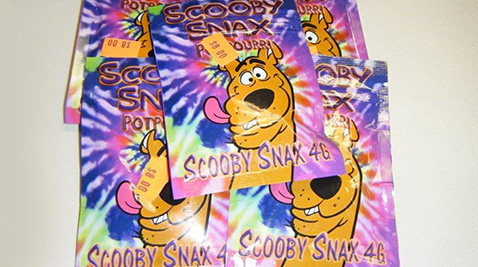

After liquefying the synthetic cannabinoids and spraying them onto organic leaves, processing sites package the mix in bright-colored pouches, labeled “not for human consumption.” But that’s with a knowing wink. After all, human consumption is the very thing distributors have in mind.

Marketed as a “legal high” and sold under the guise of incense or potpourri, synthetic cannabinoids are sold at gas stations and convenience stores across the nation.

Marketing skews toward the naïve and innocent. Retailers often refer to the drug as Scooby Snax — which is one reason the drug can entice younger users.

“They label them with cartoon figures and smiley faces and rainbows,” said Robin Smith, Kyle’s mother. “It’s very sad because the people that are making it don’t care about kids that are 14, 15, 16 years old.”

While the drug binds to the same receptors in the brain as THC, a major psychoactive ingredient in marijuana that gets users high, Frankenstein-like synthetic cannabinoids present the risk of far more dangerous, and sometimes debilitating, side effects, including brain and kidney damage and sometimes death. The problem is that the drug keeps changing, so all of the side effects keep changing, too, experts said.

“The only person, in a sense, who knows what was sprayed onto this organic material that’s sold as synthetic cannabinoids is the chemist who created that chemical,” said Eric Wish, director of the University of Maryland’s Center for Substance Abuse Research. “That chemist really has no idea what that particular chemical that he or she created will do to the human brain.”

To Ruben Baler, a health scientist administrator for the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Science Policy Branch, comparing synthetic cannabinoids to marijuana is a little like comparing gummy bears to bullets. In fact, Baler said that some synthetic cannabinoids could be 100 times more potent than “normal cannabinoids.”

“[People] could have those really adverse effects that we see in the clinics and the emergency rooms – people developing either very aggressive bouts of violence or psychotic bouts due to these cannabinoids, which we haven’t seen before even with high potency marijuana,” Baler said.

Wish added that the person experimenting with this synthetic drug is essentially playing Russian Roulette with his or her life.

Kyle took that gamble.

“I feel like someone cut off my left arm and stole from me, and I’m bitter,” said Robin Smith. “The drug doesn’t just affect the person who is using it. It affects a family, friends, and it just turns people into being somebody they are not typically.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.