WASHINGTON — Forty eight million.

That is how many people lived in hungry households in the United States in 2014, according to the Food Research and Action Center.

In order to combat this huge problem, the National Commission on Hunger recently recommended that Congress and the Obama administration create a cross-agency, coordinated national plan to end hunger.

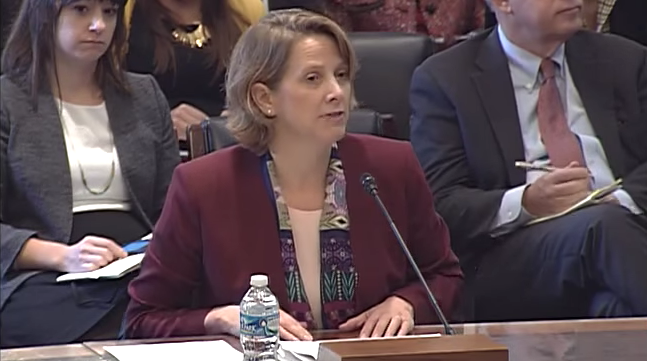

“Clearly we need to improve our current programs, but we also need to address the root causes of hunger and ensure we are counting and supporting the most vulnerable citizens of America,” commission co-chair Dr. Mariana Chilton said about the steps needed to be taken to eliminate hunger.

This commission, a 10-person bipartisan task force that began work in 2015, was the handiwork of outgoing Rep. Frank Wolf, R-Va., who was a prominent congressional advocate on hunger issues. The panel, whose members were appointed by the House and Senate, was given the job of identifying the causes of hunger and creating solutions to bring relief to those 48 million Americans.

Co-chairs Chilton and Robert Doar met with Congress on Nov. 18 — during National Hunger Awareness Week — to discuss their year-long study, their observations about the Supplemental Nutrition Program (SNAP), and some of their final recommendations for Congress. The findings will be released in a report in the upcoming weeks.

Some of the commission’s major findings were the need for job-training and assistance programs in order to lift low-income Americans (who are most likely to be hungry) out of poverty, special attention to families with children and veterans who are hungry, as well as adjustments to the SNAP program to allow families more time to stabilize after getting a job.

Originally scheduled to be released in October, the final report was delayed because the commission could not agree on several of the final recommendations, according to Doar.

Chilton said that many people will often get a job and lose their SNAP benefits before they have a chance to adjust to their new income, making them even more likely to be hungry.

There were 781,497 Marylanders who received SNAP benefits in August 2015, out of 45.4 million total recipients in the United States, according to data collected by the United States Department of Agriculture.

“From my perspective as a scientist, my sense is that many legislators and just the general public do not understand what the experience of hunger is like,” Chilton said. “They think it could be an eyeball diagnosis and see it very easily, but it manifests in many invisible and harmful ways.”

Even though Maryland is the wealthiest state in the country, there are still high rates of hunger, said Michael J. Wilson, director of Maryland Hunger Solutions, a nonprofit in Maryland that works to eliminate hunger, utilize federal hunger solution programs, encourage healthy nutrition, and train other nonprofit groups around the state.

“There is a single word answer why there is hunger in Maryland: poverty,” Wilson said in a phone interview.

Doar said at the hearing that the commission found that while SNAP does help low-income people buy food, it does not address any other underlying causes of poverty and hunger, such as lack of work.

Wilson argued that job-training programs may help some Americans, but it is not always the solution, especially for children and retirees.

Wilson said that the Maryland Department of Human Resources works with nonprofits and supports the work of local organizations. Maryland offers an array of other services, including a state-funded breakfast program.

“Maryland should lead the way,” Wilson said about finding solutions to hunger.

Wilson hoped that the commission will propose a “multilevel approach” and broad recommendations in the report.

Rep. Stacey Plaskett, D-Virgin Islands, expressed concerns at the hearing about the presence of food deserts in the United States.

Food deserts, which are low-income communities that have no supermarkets with affordable, healthy food within a reasonable distance, are present in Maryland.

One in four Baltimore residents live in a food desert, and that number is even higher for children, where the rate is 1 in 3, according to Rep. Elijah Cummings, D-Baltimore, who spoke at a pop-up farmers’ market about hunger and food deserts in Maryland last month.

“We will continue to engage in this fight for healthier lives, both in Washington and at City Hall,” Cummings said. “Yet we all know that the challenge of food deserts — and their effect on diet and health — still persists.”

Cummings represents the hungriest region in the state — Baltimore City.

According to statistics from Feeding America, Baltimore City had the highest rate of food insecurity in 2013. The nonprofit found that 22.7 percent of Baltimore residents had a lack of access to enough food for an active, healthy life, according to the USDA’s definition of food insecurity. Somerset County followed behind with 19.1 percent.

Cummings’ district had the highest food insecurity of all the Maryland congressional districts, with 19.7 percent. Sixty-seven percent of his constituents are eligible for government aid such as SNAP, WIC, TEFAP, and free school meals.

The Food Research Action Center (FRAC) ranked the Baltimore-Towson metropolitan area as 79th in food hardship, which is defined as a “struggle to put food on the table”, in 2013-2014, with 16.5 percent of people identifying as having difficulties affording food. Maryland ranked 42nd out of 50 states, with 14.0 percent facing food hardships.

Chilton said that the commission was only able to study food deserts briefly, yet heard from many citizens who testified throughout the country that people lacked the money to buy food and had no access to transportation to get food.

Doar said the commission urged the USDA to approve more stores to participate in the SNAP program to encourage more availability of food in these food deserts, both urban and rural.

Cummings said at the farmer’s market that the local and federal governments and businesses will fight for expanded access to healthy foods, but asked his constituents to continue demanding such healthy food.

“At the end of the day, our health and survival is up to us,” Cummings said.