WASHINGTON — More than 400,000 blood samples belonging to veterans from all over the country are in freezers located in a quiet storage facility at the Veterans Affairs hospital in Boston.

Eventually to grow to a million samples of veterans’ DNA, researchers see in them a vast trove of potential ways of managing diseases and developing precision medicine for former service members in the United States.

All this and more is being done under the Million Veteran Program, a flagship project started in 2010 by the federal Department of Veterans Affairs.

Work is on to find precision cures for diseases and conditions veterans suffer from, by combining their health information from the VA health system with newly found genetic information. A mega-biobank of veterans’ DNA is under construction with 431,599 vials of blood — and the number is growing.

“It’s one of the largest projects of its kind in the country — of any kind, not just for veterans,” noted Dr. John Michael Gaziano, principal investigator in the program, who is also professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

The Million Veteran Program was the brainchild of the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Office of Research and Development, said Sumitra Muralidhar, program director.

Veterans also backed the program by participating in surveys and focus groups conducted by the Genetics and Public Policy Center at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, she said.

Each day, 400 to 500 veterans are giving their consent and vials of their blood that eventually will go into DNA sequencing to understand how the genes cause diseases like post-traumatic stress disorder, hypertension, diabetes, substance abuse disorders, schizophrenia and cardiac disorders, among others.

Over the course of military service, veterans are exposed to a lot of stress. The program was a way to use the VA’s extensive health records and combine them with genomic information.

That way, the agency can study how veterans react with their environment and the genetic basis of the diseases that they suffer from, said Dr. Timothy O’Leary, former chief research and development officer at the Veterans Health Administration Department of Research and Development in Washington.

“Veterans or military personnel are put into variety of stressful situations and may be exposed to biological toxins,” O’Leary said.

The need to improve treatment and make it more precise for each veteran inspired the research being conducted under the program. Since its inception in 2010, roughly $130 million has gone into recruitment and enrollment costs, biobanking, genotyping and sequencing as part of the program.

The aim is to “improve the care that we’d ultimately deliver to service members and veterans,” O’Leary added.

In two to three years, researchers aim to enroll at least a million veterans nationwide who are part of the roughly 8.5 million enrolled in the country’s VA health care system. Veterans enrollments are spread across around 50 VA hospitals and several community-based clinics.

“The rule of genetics, because the genome is so large, is ‘the more the merrier,’” O’Leary said. The genome is the complete set of genetic material in a living being.

With 431,599 veterans on board, “we are getting close to half way,” Muralidhar said. “When we started, we used to say up to a million, and we are now saying at least a million.”

She said that the program is a part of the Precision Medicine Initiative started by President Barack Obama earlier this year, so that health care providers could provide tailor-made treatment based on a patient’s genetic makeup, lifestyle, diet and others.

The aim is to enroll 100,000 individuals a year, O’Leary said. “And that’s driven by the fact that the Congress doesn’t give us an infinite amount of money to do this and so we have to be able to do it on a time scale dictated by financial considerations,” he said.

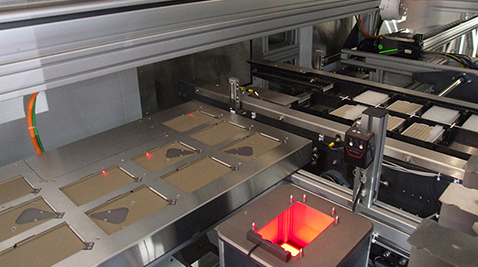

As soon as blood samples are drawn, Murlidhar explained, they are kept in vials, packed into shipping boxes having frozen ice packs in them and taken to the Boston facility, which is completely automated by robots. There, scientific staff led by the scientific director oversee the entire process as the components of the blood are separated and DNA is extracted from it.

A view of the biorepository in Boston. It shows the automated, robotic nitro-store and storage chambers maintained at minus 80 degrees with vials containing the plasma, buffy coat and DNA extracted from blood samples. Below are robotic arms maintained at minus 20 degrees. Photo Courtesy: Veterans Health Administration.

The DNA is then tested on a chip, which is customized to have 750,000 genetic biomarkers and includes African-American and Hispanic ancestry markers as well as those for common diseases like hypertension, prostate cancer and breast cancer.

Once the genetic sequencing is done, the genetic information of each veteran is stored safely on the Genomic Information System for Integrative Science or GenISIS, the computer system, which integrates it with data received from the VA medical centers.

The combined genetic and VA health information about each veteran stored on GenISIS creates a wealth of information and “investigators come to that environment and do science with it,” Gaziano said.

“It is incredibly powerful tool to understand how to study disease processes overall,” said Dr. Kyong-Mi Chang, acting chief research and development officer at the VA’s Office of Research and Development.

There are also scientific projects going on in connection with the Million Veteran Program to look into schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and Gulf War illness.

Most enrollees are in their 60s. Gaziano said that veterans from the Korean War, World War II and the Vietnam War are also enrolling in the program.

The early research has turned up some fascinating information.

Of more than 200,000 veterans whose genes were studied, 62.9 percent were found to suffer from hypertension. It was the most self-reported condition among the top 20 medical conditions that also included hyperlipidemia (high levels of fats and lipids in the blood), acid reflux, tinnitus, hearing loss, depression and diabetes, according to a paper published on the program in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology.

Veterans aged between 60 and 69 years constitute 38.4 percent of enrollees. More than half of all enrollees served in the military between August 1964 and April 1975. Army veterans, at 43.8 percent, form an overwhelmingly large segment of veterans in the research study (followed by Navy at 19.6 percent and Air Force at 15.5 percent).

Closer to home at the Baltimore VA Medical Center, 2,858 veterans so far have volunteered to give their blood samples and health information to scientific research.

Most of the conditions being studied are age-related, O’Leary said.

The Million Veteran Program is also soon going to target younger veterans who seldom come to get treated in the VA hospitals, using a web-based enrollment system.

“This is basically driven by their health care needs. Younger veterans do not access the VA health care system as often as the older veterans with chronic illnesses,” Muralidhar said.

Active duty members will also soon be enrolled into the program in collaboration with the Department of Defense, Muralidhar said.

He added that building the gene bank and research won’t necessarily stop even after blood samples from one million veterans are collected.

It is likely that the kinds of exposures that veterans will have will change over time, O’Leary said.

“So it’ll be important to be able to continue collection, so that what we learn from this remains relevant to veterans in whatever the changing nature of military service is going into the future,” he explained. “Every war is different than the last.”

The participating veterans don’t receive any compensation for participating in the research study.

But that doesn’t seem to matter.

“They (veterans) almost universally say that the reason they are participating in this program,” O’Leary said, “is to discover new knowledge that will be good for other veterans and for their children and their grandchildren.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.