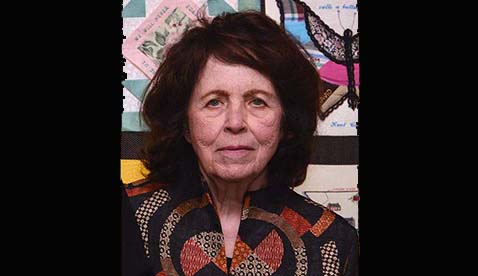

ANNAPOLIS — Shortly after her husband’s death, Roberta Roper enlisted the help of an accountant to file her taxes. That’s when she found out her family was victimized — again.

Her husband, Vincent Roper, had died suddenly from a massive heart attack on April 4, 2013. He had always done their taxes, she said.

With the April 15 income tax filing deadline looming, Roper, now 78, of Croom, Maryland, applied for an extension from the IRS. In return, she received a letter from the agency stating the return was already filed and the money sent to an individual in New Hampshire.

In 1982, Roper and her husband created the Stephanie Roper Committee and Foundation Inc. in memory of their daughter, a college student who was kidnapped, raped, tortured and murdered on her way home on April 3, 1982.

Having spent 33 years as an advocate for crime victims, and 20 years as the onetime head of the foundation, now part of the Maryland Crime Victims’ Resource Center, Roper said, she knew immediately to file a police report.

Though she cannot prove it, Roper said, she thinks someone used the information provided in her husband’s obituary to file the fraudulent return.

Roper is one of a rising number of victims of tax-fraud identity theft, a list that includes Maryland’s attorney general, Brian Frosh.

“Tax identity theft” is when an individual uses a taxpayer’s Social Security number to fraudulently file an income tax return and receive a refund, according to the FTC.

From the IRS to filing a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission to working with her banks to further secure her information, recovering from identity theft went “on and on,” Roper said.

“It was certainly an intrusion in my life that I didn’t need,” Roper said. “And it came at such an awful time.”

After more than six months, Roper received her refund and was notified by the IRS that her case was closed.

Maryland is one of many states working with the IRS to try to prevent and stop identity theft tax fraud. Complaints of tax fraud are on the rise, according to the FTC, and some victims face financial hardship as they wait for the IRS to resolve their case and give them their income tax return.

Tax fraud identity theft is a “huge issue,” which has grown exponentially over the last five years, according to Rob Douglas, an expert on identity theft.

The recent trend is “bad actors,” many from organized crime, have moved from filing fraudulent returns at the federal level to the state level, Douglas said.

Over the past two years, the federal government has made it a priority to limit the number of fraudulent tax returns, Douglas said, so last year was a “transitional year” and people began filing more illegal returns at the state level.

“If I am Maryland, I want to make sure I am not an easy target,” Douglas said.

Maryland’s comptroller, Peter Franchot, proposed legislation on Dec. 1 to boost penalties for tax -related crimes and increase the state’s prevention and enforcement efforts.

Franchot, a Democrat, is responsible for Maryland’s revenues, including tax collection. His proposed Taxpayer Protection Act is designed to allow officials to better detect and prevent fraudulent tax activity.

The act would increase the statute of limitations for tax-related crimes to six years, allowing officials more time to fully investigate crimes and press charges. The current statute of limitations is three years.

Under Franchot’s proposed law, people committing certain tax-related crimes would face felony instead of misdemeanor charges, according to the comptroller’s office.

For those tax preparers under investigation for committing fraud, officials could place injunctions to stop them from filing more returns, according to Franchot.

The act would also provide officers in the comptroller’s field enforcement division with additional powers needed to enforce tax law, including issuing subpoenas and signing charging documents, Franchot said.

“Tax fraud and identity theft associated with it are a growing concern across the country as personal information becomes more and more available to perpetrators and as schemes become more and more sophisticated,” Franchot said.

Between Jan. 1 and Oct. 31, 2015, the IRS has stopped or rejected 4.7 million suspicious returns worth $10.4 billion, according to the IRS. Of those, 1.3 million were confirmed instances of identity theft, worth $7.7 billion.

“We think there’s going to be a lot more sophisticated programs to attack agencies in states like ours and giving us this legislative authority, extra enforcement, will allow us — we estimate — to head off $20 million in prospective fraud schemes,” Franchot said.

The main goal of the act is to protect taxpayer’s money and privacy, creating a “very strong initiative going after the bad guys,” Franchot said.

In 2007, the year Franchot became comptroller, his office stopped 314 fraudulent returns worth approximately $656,000, according to Andrew Friedson, communications director for the comptroller.

Since then, the number of fraudulent returns has increased each year. In 2015, as of Oct. 31, the comptroller’s office has stopped 18,704 fraudulent returns worth more than $38 million, according to Friedson.

The comptroller’s office did not have information about how much it has paid out in fraudulent tax returns, according to Friedson.

“It would obviously be impossible to determine how many refunds are awarded on the basis of fraudulent filings, because if we are aware of them, then we’re able to prevent them from going out the door,” said Friedson.

“It would be naive of us to claim that we have a 100 percent rate of detection,” Friedson said.

The IRS is partnering with state tax organizations and the private-sector tax industry to try and improve identity theft refund fraud protections in the coming tax season, according to an October news release from the IRS.

In November, Franchot signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the IRS to share information to help detect refund fraud and increase security measures.

The purpose of the memorandum is “for broad information sharing (between) tax administrators across the country — states, federal and private sector entities,” Friedson said in an email. The “regular and constant communication” allows different agencies to work closely and more efficiently during investigations combatting fraud.

‘Double payout’

This spring, Attorney General Brian Frosh received a letter from the IRS, dated May 1, 2015, confirming the receipt of his 1040A form, used to file individual federal income tax returns.

But Frosh had yet to file his return.

“I’m the guy who always turns his papers in in the last minute,” he said. “I always get an extension. “

Knowing it was tax fraud, the first thing Frosh did was call the IRS, where he spent 40 minutes on the phone without speaking with a person.

Working with the IRS turned into a “nuisance” and an “inconvenient” investment of time on the phone and with paperwork, Frosh said.

Congress has reduced the IRS budget by more than $1.2 billion between fiscal years 2010 and 2015 — from $12.5 billion to $10.9 billion — according to a May 2015 report from the Treasury Inspector General for the Tax Administration.

IRS budget cuts create more delays and barriers in resolving tax fraud cases, said Robin McKinney, director of the Maryland CASH Campaign, an organization working to promote financial security for low-income families, including free tax preparation.

“At some point, you’re not just cutting into fat anymore, you’re cutting into bone,” McKinney said.

Though Frosh does not know how someone got his personal information to file a fraudulent return, the state’s top legal officer said he did receive a notice last year from his health insurer that its database was hacked and his personal information was possibly compromised.

Over the past 10 years, a number of data breaches in the U.S. have yielded the personal information of more than 800 million people, including children, Frosh said. Because there are only about 300 million people in the U.S., duplicates are likely.

With data breaches from companies like Target to health insurance provider Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield, “the odds are pretty good if you’re an adult” that your personal information has been compromised, Frosh said.

Now, every quarter, Frosh receives a letter from the IRS saying they are investigating his claim of tax fraud, Frosh said. Though he cannot be sure, Frosh suspects that the IRS paid out the fraudulent return.

The Taxpayer Advocate Service, an independent part of the IRS with agencies in every state, works on behalf taxpayers to resolve issues with the IRS, including cases of tax fraud.

Over the past couple of years, the service is “drowning” in cases related to identity theft-related fraudulent tax returns, according to James Leith, a taxpayer advocate for Maryland.

Between Oct. 1, 2014, and Sept. 30, 2015, identity theft made up 24 percent of the cases Maryland’s Taxpayer Advocate service worked on. The next most common issue was income verification, proof of how much money an individual made, which made up 13 percent of its caseload, according to data from the service.

In fraudulent return cases, many taxpayers are frustrated with the nuisance of having to remedy the incorrect information in their accounts, Leith said. In some cases, people face an “economic burden” because they were counting on the money from their tax return.

“It’s a lot of money when people live off this refund,” Leith said.

As of Nov. 20, for the 2015 filing season, the IRS processed more than 150 million income tax returns. Of those, more than 109 million received refunds, which were on average worth $2,785, according to the IRS.

Though the time it takes to resolve an identity fraud case is down from 2014, on average it takes 75 days to resolve one of these cases, according to data from the service.

During fiscal year 2015, of the 863 identity theft cases the advocate service resolved, in 90 percent of the cases taxpayers received their refund and the fraudulent information was removed from their account, according to data from the service.

That means nine out of 10 people are “actual victims” and deserve their refund, Leith said. “They’re entitled to lots and lots of relief” and are not trying to cheat the system.

“We’re not talking about a small subset of taxpayers,” Leith said. “There’s hundreds of these, thousands of these folks.”

The Maryland CASH campaign, which offers financial services to low-income populations, sees victims of tax fraud in cases where someone fraudulently claims a child as their dependent, according to McKinney.

The legitimate taxpayer cannot rightfully claim their dependent, which delays their refund and sends the “whole system into a tailspin,” McKinney said.

More than 50 percent of the campaign’s clients make less than $20,000 a year, so “they’re very vulnerable to the amount of any money not coming in,” McKinney said. In cases of fraud, the campaign enlists the help of the taxpayer advocate, but the refund can still be delayed.

The federal tax agencies have “gotten better at identifying the types of returns that come in that set off bells and whistles, ” Douglas said.

The government, either state or federal, has to provide the payout to the correct taxpayer. The best defense, Douglas said, is to file taxes as early as possible.

The “first in the system is going to get the money,” Douglas said. “The rightful taxpayer will still get their refund, but it will be delayed significantly.”

In 2013, the IRS estimated it either prevented or recovered $24.2 billion worth, or 81 percent, of fraudulent returns related to identity theft, according to a January report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

But of detected refunds related to identity theft, the IRS paid out $5.8 billion in fraudulent returns, according to the report.

Comparing those who file fraudulent tax returns to “house burglars,” Douglas said, identity thieves will communicate to find the easiest states to target and find the “paths of least resistance.”

If the fraudulent refund is not recovered, then the IRS has a “double payout” as they are obligated to give the rightful taxpayer their return, according to Leith.

“It’s a drain on the treasury,” Leith said.

Tax fraud was one of the most complained-about issues for the Maryland Attorney General’s office last spring, according to Jeff Karberg, identity theft program administrator for the Maryland Attorney General.

It does not require a “tremendous” amount of information to file a fraudulent tax return, and data breaches and hacking episodes are exposing personal information every day, Karberg said. “Information is just as valuable as money these days.”

In 2014, tax fraud was the No. 1 consumer identity theft complaint for the fifth consecutive year, according to the FTC.

In Maryland, between Jan.1 and Oct. 31, the FTC received 5,856 tax fraud identity theft complaints, increasing 220 percent from 2014, according to Jay Mayfield, an FTC spokesman.

Though the increase could come from greater media attention, allowing more people to know they need to complain, the FTC does not have enough information through statistics to assign a cause, Mayfield said.

A tiny fraction of these cases are wage-fraud related, where someone uses a Social Security number to steal someone else’s wage using a paycheck system, according to Mayfield.

In 2014, victims in Maryland went from accounting for 1.7 percent of tax fraud identity theft complaints in the U.S., to accounting for 2.7 percent of national complaints by the end of October 2015, according to data from the FTC.

Roper has taken steps to protect her account, like having passwords that only she and her banks know and using a credit card with a chip in it.

But, “crime doesn’t discriminate,” Roper said. “Anybody is vulnerable to these kinds of crimes.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.