ANNAPOLIS – Just before his death at age 60, Rosalind Kipping’s brother told her his death would be one of suffocation.

An orthopedic surgeon, Robert Kipping was diagnosed with interstitial lung disease and was rejected as a candidate for a lung transplant due to a previous bypass surgery.

As a doctor, Rosalind Kipping said, he would have been able to control his own death, but an unexpected heart attack made his escape plan unnecessary.

“Robert did not want to die … But he knew that he was approaching the end of his endurance, and had made his plan for escape,” said Rosalind Kipping, 79. “Should I reach the end of my endurance, I want to know that a plan for escape is available to me.”

Rosalind Kipping was one of dozens who signed up to testify at a joint House committee meeting Friday on the End of Life Option Act, which would allow terminally ill patients in Maryland to choose to end their own lives.

People with a maximum of six months left to live would have the right to ask a doctor to prescribe lethal medication that must be self-administered, according to the bill.

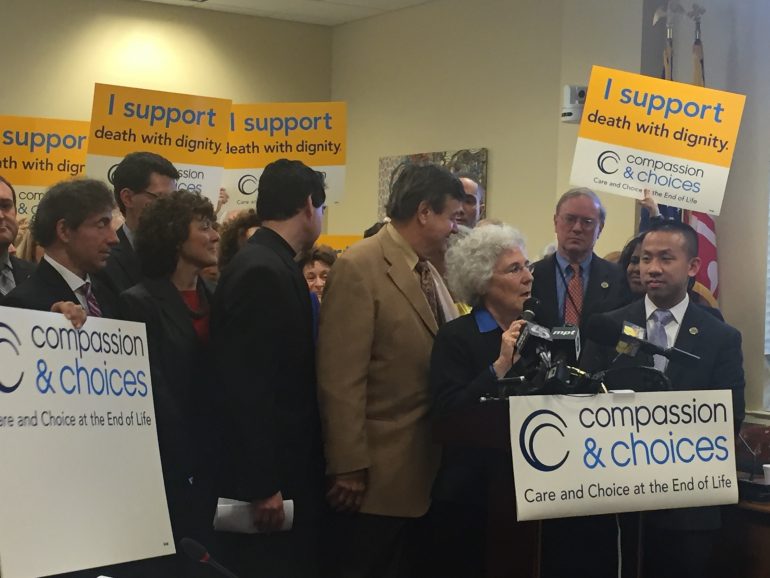

The bill was introduced in the 2015 Maryland General Assembly session as the Right to Try Act, or “Death with Dignity” bill, but did not make it past the committee. This year, it has come back with a new name and other modifications that legislators and supporters hope will get it passed.

“We were told in the hearing last year that all death involved dignity, but dignity is not really the issue,” said Delegate Shane Pendergrass, D-Howard, the bill’s House co-sponsor, before the hearing. “We’ve made several changes, and I’m optimistic, but one never knows.”

The 2016 bill requires patients to have a private consultation with their doctor before prescribing the drug, and they must request the lethal medication three times – twice verbally and once in writing – and have two witnesses approve their decision. One witness may not be a relative or beneficiary of the patient.

“There are people who are suffering, and I don’t want to have to face that,” Pendergrass said. “I see what people go through, and I want to be able to ease my pain or my mother’s and father’s pain. They should have the option to control the process.”

The bill and its Senate version are named for former Annapolis Alderman Richard E. Israel and former Annapolis Mayor Roger “Pip” Moyer, who both died in 2015 after suffering long-term battles with Parkinson’s Disease.

A religion or government should not have the right to make choices for an individual, said Sally Hunt, a volunteer for national nonprofit Compassion and Choices, which works to expand options for those nearing death.

“I’m a very independent person,” Hunt said, “and I make a lot of other decisions in my life. I am the only one who can decide what’s right for me, and I think I have the right to end my life the same way I live it.”

Those against the bill believe people should live life until its natural end.

“If you had a child who had two months left to live, would you let them take a pill that would kill them, or would you opt to be with them?” said Ruby Wilson, a member of the Social Justice Committee at the Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Glyndon, Maryland. “It’s no different than with an adult. It’s suicide.”

Dr. Kevin Donovan, the director of the Center of Clinical Bioethics at Georgetown University, a Catholic institution, said the bill contradicts progressivism and is “deceitful,” and patients should be kept alive as long as possible.

“As a society, we should be offering patients love and support,” Donovan said. “We shouldn’t take (their) hands and lead them to their deaths. The sick and dying deserve so much better.”

According to a 2015 Goucher poll, 60 percent of Marylanders support the bill. If passed, Maryland would be the fifth state, behind Oregon, Washington, Vermont and California, to allow people the choice to end their lives.

“Those are pretty good numbers,” Pendergrass said. “The time has come.”

-30-