COLLEGE PARK, Maryland – The state of Maryland, whose voters experienced long lines in the 2012 election, made big changes to the voting system to correct wait time problems and accommodate a group of newly eligible voters: ex-felons.

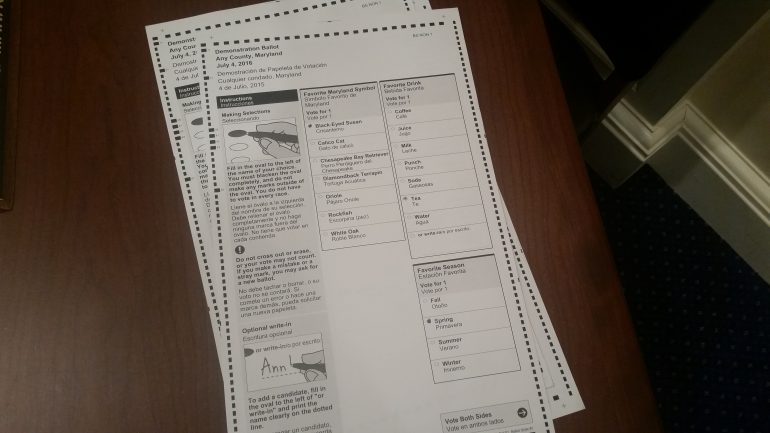

Those that make their way to the polls on Tuesday will find the most noticeable change to be the return to paper ballots instead of the electronic touch-screen machines the state had used since 2002.

The new balloting system was tested by an increase in the number of early voters, but official said the results were positive.

This year’s 122,880 first-day voters was a dramatic increase from the 78,286 who cast votes on the first day they could before the 2012 election, according to state Board of Elections data. Through the first six days of 2016 early voting, an average of more than 101,000 ballots were cast per day. Over five days of 2012’s early voting period, about 86,000 voted per day.

The state also is revising its methods for distributing polling place workers and balloting materials to adjust to the paper balloting system.

“We’ve moved away from a rigid formula to provide some flexibility that considers historical turnout,” said Nikki Charlson, the deputy state administrator of the elections board. “There’s less equipment in the facility, so we are still learning voter behavior with the new voting system.”

The paper ballot system is intended to not only combat wait times, but also to eliminate concerns about illegal voting practices. Officials were concerned the digital touch machines could be subject to hacking and voter fraud.

Touch screen ballots also left no paper trail, making any recounts needed to inspect the original votes unreliable, if not impossible to conduct.

With the new technology, provided by the Nebraska-based company Election Systems and Software, voters fill out their paper ballots and insert them into a scanner that interprets the markings. Any faulty ballots will prompt the printing of a new ballot to be resubmitted.

“This will be the first presidential election where we use paper ballots, so I do anticipate there will be some bottlenecks because of that,” said Alisha Alexander, elections administrator for the Prince George’s County Board of Elections. “We have hired additional election judges, but because there is no time limit (for voters), that is where there could be a bottleneck.”

Maryland was among the three states (Florida and South Carolina were the others) in 2012 with the longest lines in the country, prompting researchers Christopher Famighetti, Amanda Melillo and Myrna Perez of the Brennan Center for Justice to analyze precinct-level voting.

The researchers found in their 2014 study that a lack of poll station workers and a limited number of voting machines contributed to long lines, especially in minority areas.

In the 10 Maryland precincts with the lowest number of voting machines, Hispanic citizens of voting age represented 19 percent of the population, nearly triple the statewide average of seven percent, the study said. A lack of resources negatively affects voting totals, as lengthy wait times tend to discourage voters.

“When voters are waiting up to an hour or in some cases four or five hours, there’s the danger that voters will leave the line and choose not to cast a ballot,” Famighetti said.

The new paper ballot system was tested in Maryland during the primary election, and only 14 of the 4,000 new machines malfunctioned, according to the Washington Post. Maryland Board of Elections Administrator Linda Lamone said that voters responded very well to the paper ballots and there were no difficulties or delays using them.

Voter fraud already was rare nationally, but the extra measures will make it practically impossible in this year’s election, Lamone said.

“There was a recent report that came out that examined the vote in the entire United States in the past 10 years,” she said. “And in the millions and millions and millions of votes cast, I think they found 30 fraudulent votes.”

Fraud might be a minuscule concern with this year’s election in Maryland, but long lines remain an issue, especially with a percentage of ex-felons coming to the polls for the first time. More than 40,000 ex-felons regained the right to vote in March, thanks to the Maryland legislature’s override of a veto by Republican Gov. Larry Hogan.

Legislation restored voting rights for those on parole and probation who previously were prevented from voting until completely exiting the criminal justice system.

Grassroots organization Maryland Communities United is working to make sure the potential new voters cast their ballots in this election, member Reginald Smith said.

Smith said the group registered 500 ex-felons to vote in the first month after the bill passed. In three months, 2,000 signed up with Communities United, he said.

“We busted,” Smith said. “We definitely had some crazy, astonishing numbers for voter registration.”

Communities United operates out of Baltimore, where 20,000 of the state’s 44,000 ex-felons reside. But the 2,000 ex-felons registered account for only 10 percent of ex-felons recently declared eligible within the city limits.

Registration doesn’t guarantee people will cast ballots in the presidential election, either. While Smith said he has talked to ex-felons reminding them to vote or encouraging them to register, often he has been met with indifference.

“Those are the ones that would be saying, ‘It doesn’t make a difference if we vote because nothing’s gonna change,’” Smith said. “Those are the ones that I’m telling, ‘If you don’t vote, nothing’s gonna change. That’s why you vote.’

“Those are the ones that I’ve really got my foot on their neck, so to speak, to try to make them register and do something positive.”

A widely-cited study by University of Minnesota professor Christopher Uggen and New York University professor Jeff Manza found that ex-felons who voted in the 1996 election were far less likely to have committed crimes in the following four years. They suggest that as ex-felons begin voting and participating in the community, “it seems likely that many will bring their behavior into line with the expectations of the citizen role, avoiding further contact with the criminal justice system.”

Across Maryland, 65 percent of the disenfranchised ex-felons are black, while the state’s total black population is 30 percent.

Nationwide, one in 13 African-American adults is barred from voting because he or she is imprisoned, on probation or parole, according to the non-profit criminal justice-focused organization The Sentencing Project.