OAKLAND, Maryland – On a brisk Wednesday morning in October, a seventh-grade boy in a plaid shirt leaves his family farm, hops on his four-wheeler and drives through the rolling hills of western Maryland, flanked by windmills and livestock, ready to start his day at school.

Two girls wearing long dresses and delicate white prayer caps pull up at the school on a red tractor soon after.

Inside, a first-grader clad in suspenders over a plain red shirt and solid black pants studies the screen of an iPad intently. And at recess, a middle school girl wearing an ankle–length plain purple dress and white head-covering runs and jumps to hit a volleyball to a classmate.

This is Swan Meadow School: a three-classroom public institution surrounded by the mountains of rural Garrett County, for kindergarten through eighth-grade students of Gortner, Maryland.

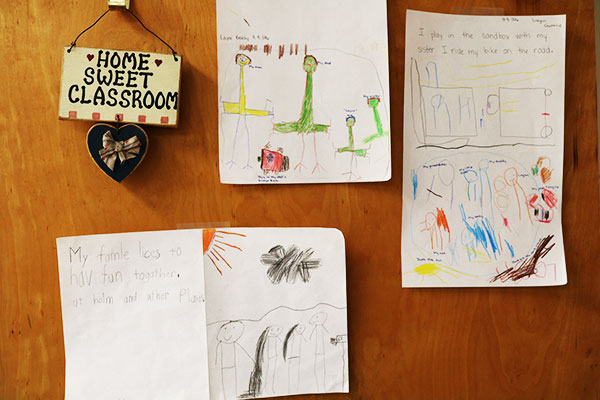

In many ways, Swan Meadow is just like any other elementary or middle school. The day begins with morning announcements followed by the Pledge of Allegiance. Students learn math, science, social studies and language arts according to Common Core State Standards.

But Swan Meadow is far from typical.

Being in the agrarian town of Gortner, most students at Swan Meadow are members of farm-owning families. And many of those families are Mennonites, New Order and Beachy Amish, Christian sects that live a “modest” lifestyle, but accept the use of electricity, unlike the original “Old Order” Amish. They own tractors and oftentimes use them as a mode of transportation.

At its inception in 1892, Swan Meadow was a one-room schoolhouse. Today it is one of Maryland’s smallest public schools, and in one of the most conservative parts of the state.

This year, there are 42 students at Swan Meadow, taught by five teachers, one of whom is also the principal.

Unlike a lot of children, most Swan Meadow students are not off to soccer practice or club meetings after school. Many head home to work on their family farm.

One eighth-grade student lives on a cattle farm. A seventh grader has goats and chickens to which he tends after school. (Students are not named or pictured in this story for privacy and religious reasons.)

Ida Swartzentruber is a member of the New Order Amish community in Gortner. She sent her three children to Swan Meadow.

Swartzentruber said her children woke up around 5:30 a.m. to do chores before catching the bus to school. When they came home around 3 p.m., work on the farm began.

“We have calves to feed, chickens to feed, cows to milk,” Swartzentruber said.

For Liz Gilbert, the sole middle school teacher, this means she hardly assigns homework.

So, Gilbert said, she packs the school day with learning, while assignments for home are only items students do not finish in class. Many of them do not have computer access to do homework anyway.

The lack of electronics in Gortner homes, especially Amish and Mennonite, means teachers strike a delicate balance at Swan Meadow.

Swan Meadow has Macbook Air laptops, iPads, desktop computers and Smart Boards. All students — Amish, Mennonite and “English,” or those outside of the conservative faith — use them.

“There’s a lot of trust involved” between teachers and parents, Gilbert said, including careful supervision of technology in the classroom to ensure students use the internet for learning purposes only.

“I hate them,” one seventh-grader said about the computers at school. “I’d much rather use pencil and paper.”

There is also a lot of trust with the curriculum.

“I have to preview everything to make sure it’s appropriate,” Amy Snyder said. She is the reading specialist for kindergarten through second grade students.

Snyder said she recently skipped a story in the curriculum about magic. She decided to choose a different story she deemed more suitable for her conservative students.

“It’s me being sensitive and courteous,” Snyder said.

Swan Meadow is also unique in that its graduates do not usually continue to a public high school, Gilbert said. The U.S. Supreme Court in 1972 ruled Amish children cannot be forced to attend school past the eighth grade.

Some Amish and Mennonite students at Swan Meadow end their education after middle school to work on their families’ farms full-time. Others are homeschooled for high school.

Swartzentruber said she let her children decide whether to continue their education after eighth grade. Her daughter received a GED diploma through a program offered at Swan Meadow.

Some English students also said they will be homeschooled after their time at Swan Meadow. Two seventh-grade students told the University of Maryland’s Capital News Service they will continue working on their family’s farms and eventually take over the business.

Gilbert knows that for many of her students, Swan Meadow is the end of their formal education. And she wants to make their schooling worthwhile while they are there.

So teachers make do with what they have at the tiny school — which is not a lot.

Being a small school in a rural and conservative area means it operates differently from other public schools.

“The hardest thing is balancing the curriculum,” Snyder said.

Each instructor at Swan Meadow teaches three grades, usually at the same time. Kindergarten through second-grade students are in one room, third through fifth graders are in another, and middle school students learn in the third classroom.

An open area serves as a library and the basement is used as a multipurpose room where students eat lunch and have gym classes on colder days.

Being in a rural area means the school has one of the slowest internet connections in the state. According to Nathaniel Watkins, the chief information officer for Garrett County, it would have been too costly to install the same connection other Maryland schools have.

Arlene Lantz is the math teacher for all nine grades at Swan Meadow.

Some days video lessons have had to be pushed back because the connection is so slow, Lantz said.

“Specials” classes like music or gym are once per week. Teachers for those subjects, as well as a guidance counselor, visit from other schools. Principal Jessica Fratz said her school does not have the staffing to provide these classes more frequently.

After her students complete the fifth grade, they have the option to leave Swan Meadow. Their options broaden with nearby middle schools that offer clubs and more activities, though most stay, Fratz said.

That is not to say the school has not made numerous strides in its 124 years. When Gilbert came to the school two and a half decades ago, it was in the beginning phases of modernization. Textbooks were outdated and technology was scarce.

But while Swan Meadow has come a long way since then, Gilbert said, she wishes she had more for the students.

She said middle schools nearby have science labs filled with new equipment. Swan Meadow’s middle school classroom has three microscopes that sit on the same small bookshelf as the texts and student binders for other subjects.

So teachers improvise.

Science classes are often taken outside of the classroom. Students helped build a low tunnel greenhouse where they grow green peppers and watermelon.

They created a wildflower meadow and a sanctuary along the side of the school for monarch butterflies. Students wade in Cherry Creek, just down the road, and take samples of the water for a stream restoration project.

Gilbert just wishes they had more experiences available for her students. She grew up in the Washington, D.C., area, about four hours away by car. She knows what the museums around the District have to offer. Gilbert said Swan Meadow does not have the funds for these trips.

The community of Gortner is an important piece of helping Swan Meadow financially and otherwise.

The biggest community support comes through the parent teacher organization.

In 1957, Swan Meadow was at risk for closure by the government due to overcrowding. Students were divided into two groups, and went every other day to the one-room school taught by a single teacher.

The Parent Teacher Organization struck a deal with the county government. In exchange for $15,000 for building materials, parents of Swan Meadow provided the land and all of the labor for the new schoolhouse.

The parent teacher organization holds an annual Harvest Sale, the community’s largest fundraiser for the school. Families donate homemade food and furniture, quilts and rugs, and have used the proceeds to buy Macbook Air laptops.

The teachers at Swan Meadow are not strangers to finding ulterior forms of getting resources. They incorporate funding strategies into their lessons.

Lantz said she is helping students work on a presentation to the Parent Teacher Organization outlining costs for a pavilion that would give Swan Meadow an outdoor classroom.

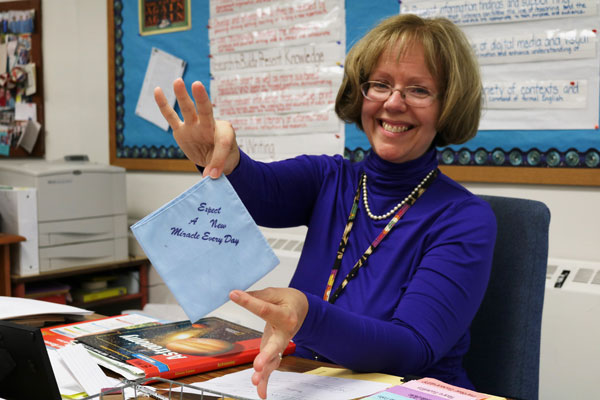

And Gilbert, the 2002 to 2003 Garrett County Teacher of the Year and a 2011 Maryland State Department of Education Master Teacher, said she includes grant-writing in her lessons.

Gilbert also goes to professional development courses, and usually brings back the free materials to share in her own classroom.

Three of Swan Meadow’s five teachers have spent at least 10 years there. And they all could easily leave to teach at a school nearby with more funding and resources that would make lesson planning a lot easier. But the close-knit community in Gortner keeps them coming back.

Erica Foley, the third-, fourth- and fifth-grade teacher, said unlike at other schools, a new year does not entail starting on a blank page.

“We really hit the ground running,” Foley said. “I really know the kids.”

Foley said she can meet students’ needs in a better way by individually tailoring lessons to their strengths and weaknesses.

One of the best aspects of Swan Meadow is the strong foundation in ethics and mutual support that the community instills in the students, Gilbert said.

“We’re kind of all here together to do the best we can every day for each other and the school,” Gilbert said. “It is a real joy to be here.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.