ANNAPOLIS, Maryland — In 2014, Alexa Fraser’s 90-year-old father successfully ended his life with a gun to the head after two failed suicide attempts.

Her father, whom Fraser described as a “fiercely independent person,” suffered from Parkinson’s disease, a progressive movement disorder marked by involuntary tremors and slowed movement. His condition had worsened and he feared he would be kept alive beyond his will in a nursing home so he decided to take action, Fraser said.

Since his death, Fraser has been on the forefront of Maryland’s legal aid-in-dying movement, which advocates to allow patients with a terminal diagnosis to receive a lethal prescription to painlessly end their life.

The Maryland legislature for the third year in a row is considering a joint House and Senate bill that would legalize aid-in-dying. Sponsors of previous bills have withdrawn them before a vote, citing lack of support.

“Mom has told the hospice nurse — on numerous occasions — that she just wants to go to sleep and not wake up,” Kevin Gillogly from Silver Spring, Maryland, wrote in testimony for a Thursday hearing before a pair of House committees. His mother entered hospice care in December. “As a son, I want my mom to live out her life — and death — with dignity.”

The language surrounding the issue has been contentious. Opponents resist the term legal aid-in-dying, deeming it instead as physician-assisted suicide.

“It is very important to be up front, clear and honest about what this is,” Anita Cameron, director of minority outreach for Not Dead Yet, wrote in testimony submitted for the hearing. Cameron, who also had two degenerative disabilities, wrote that the bill is referring to physician-assisted suicide.

“Couching it in pretty language and hiding the truth is disingenuous, at best, and dangerous, at worst.”

The bill would undermine the doctor-patient relationship, according to a Maryland physician.

“Instead of the doctor’s role being one of caring for those at all stages, including at the end of life, the shift would be toward patient abandonment at a time when a patient is most vulnerable,” Dr. Ellen McInerney, who practices internal medicine in Edgewater, Maryland, wrote in testimony to the committee.

Fraser, who was diagnosed with a rare form of uterine cancer in December, remains optimistic that the bills will garner enough support this year to pass. Although this legislation may eventually directly affect her own end-of-life choices, Fraser said, she continues her fight for her friends and family, not herself.

“I don’t know when I’m going to die, but what I know is there are people who right now are dying in ways they don’t want to,” Fraser said. “That is what is urgent. My situation isn’t urgent.”

Fraser testified Thursday that her son has been recently diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, a diagnosis that has not changed her support for death with dignity.

Delegate Shane Pendergrass, D-Howard, and Sen. Guy Guzzone, D-Howard, are sponsoring the bills in their respective chambers.

Pendergrass said her support for the bill stems from witnessing her grandfather’s battle with Parkinson’s. Her parents eventually no longer took her to see him in a nursing home because they didn’t want her to remember him in a debilitated state.

His brain was “absolutely alert to the very end,” Pendergrass said, but “he was locked in his body and his body was locked away from us.”

“We’re all one bad death away from supporting this bill,” Pendergrass added. “Nobody wants to see their family suffer.”

The climate surrounding the issue appears to have shifted in favor of the bill since 2014, the first year it was considered.

In 2016, the Maryland State Medical Society, composed of 8,000 licensed physicians, changed its position on aid-in-dying from opposition to neutral after 65 percent of its members advocated for either support or a neutral position on the legislation.

Delegate Clarence Lam, D-Baltimore and Howard, told the University of Maryland’s Capital News Service that as a physician, he supports the bill because it enables the patients to have control over their own end-of-life decisions.

“It’s a very difficult time for patients and I’ve seen folks face some very difficult, challenging decisions,” Lam said. “For me it’s really a patient empowerment bill.”

Moreover, 69 percent of Americans say doctors should be able to end a patient’s life by painless means, according to a 2016 Gallup poll.

“I don’t see this as a partisan issue,” Lam said. “The tide of public support … has really gone in the direction in favor of this type of legislation and we feel that if folks are able to set aside their partisan biases that people will act in accordance with what’s best or their community and the other constituents (who) support this bill.”

If the bill passes, Maryland would join six other states—Oregon, Washington, Montana, Vermont, California and Colorado—that allow legal aid-in-dying. Congress is also reviewing a Washington, D.C., Council bill that would authorize the end-of-life option.

The Maryland Catholic Conference and some disability rights groups remain opposed to legal aid-in-dying legislation.

Lori Scott, a director at disability rights organization The Arc Maryland, said it’s not uncommon for someone with a disability to feel like a burden to family members, which could lead them to feel compelled to request a lethal prescription. She fears this could affect her own daughter, who is wheelchair-bound, she added.

“Disabled people are vulnerable because they like to have the assurance of people that they work with and they want to have their approval,” Scott said. “They may undertake something that they really shouldn’t be doing or don’t want to do, but want to please a provider or please a family member.”

However, Scott said, a doctor could incorrectly give a terminal diagnosis causing “someone to end their life prematurely—an irrevocable decision,” adding that a six-month prognosis can often be “unreliable.”

Pendergrass said the bill is “tightly crafted” to protect patients from this type of abuse.

Patients eligible for the lethal medication must have two doctors diagnose them with a terminal illness with only six months or less to live, the patient must be a mentally competent adult, they must issue one oral request followed by a written request, there must be two witnesses, including one who could not directly benefit from their death, and the patient must be able to self-administer the drug.

“There are a lot of concerns about how patients may be coerced or how physicians may … lean towards greater treatment or lean towards greater end-of-life options,” Lam said. “The bill strikes a good balance between those competing concerns to make sure there are strong safeguards in place.”

Dr. Samuel Kerstein, a philosophy professor at the University of Maryland, said legal aid-in-dying legislation may be garnering more support as this generation — who have had more control over their lives than previous generations — want to be able to control their end-of-life choices as well.

Many of the arguments for legal aid-in-dying legislation — easing suffering, respecting a person’s choices and individual liberty — could also be used to support arguments for legalizing aid-in-dying for non-terminal patients as well, such as a chronically depressed individual who wanted to end his or her suffering, Kerstein added.

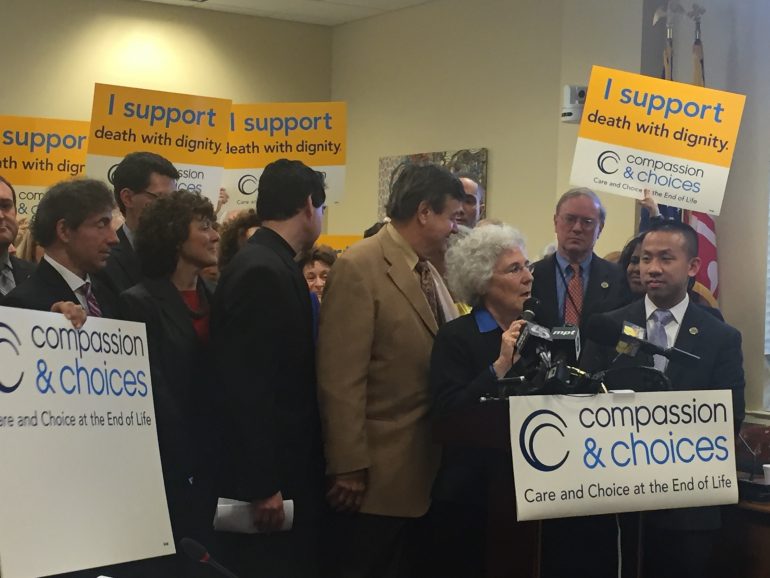

But Donna Edwards, Compassion and Choices Maryland campaign manager, said legal aid-in-dying legislation is far from suicide.

“The definition of suicide is a mentally incompetent person, who otherwise is fairly healthy who wants to end their life,” Edwards said. “The patients who take this, they are already terminal. They have done everything they can do to save their life. This is at the end of their lives when they decide how and the when, but the disease is killing them.”

Scott said she thinks instead of legal aid-in-dying legislation, Maryland should allocate more resources toward palliative care, which focuses on providing relief from pain, hospice care and expanding education.

“This is an option that shouldn’t even be on the table for people,” Scott said.

Fraser said palliative care and aid-in-dying aren’t mutually exclusive, adding that many people who request lethal medication don’t end up taking it, but rather use it as a source of comfort. About one-third of patients who request the prescription don’t use it, according to a 2013 report by the Oregon Public Health Division.

“This is a totally voluntary bill,” Fraser said. “If you don’t like it, don’t use it. But it’s a two-stage bill. The first stage is the legislature approves it, and then every person, with the help of their family, their doctors, their conscience and their ministers, … reaches their own conclusion.”

If the bill passes through both chambers, Gov. Larry Hogan, a Catholic, could veto it. Although he hasn’t made any public statements on the issue recently, in 2014 Hogan told a diocesan magazine, The Catholic Standard, that he would oppose the measure.

“I believe in the sanctity of human life, and I believe a physician’s role is to save lives, not terminate them,” Hogan said in that report.

A statement from the governor was unavailable at press time on Thursday afternoon.

However, Pendergrass said she doesn’t assume Hogan would veto the bill because of his religious beliefs.

“The governor has been through cancer treatment,” Pendergrass said. “I’m sure he’s suffered—not that he had a terminal diagnosis—but I suspect he came across people who did. I don’t think that they governor would want people to suffer.”

Fraser, a Unitarian Universalist minister, said there is a misconception that anyone of faith has a common view on this issue, adding that many faith leaders who have seen their congregants suffer are becoming more bold in speaking out in favor of legal aid-in-dying.

“We in public office are entrusted to keep the church and the state separate,” Pendergrass said. “We can have our personal beliefs, but we can know that our values may be different from some people and we can give them the ability to use this as one more tool.”

–Capital News Service reporter Carrie Snurr contributed to this story.