ANNAPOLIS, Maryland — At a press conference Friday, Gov. Larry Hogan sought to rally support for a bill that would set up an independent, non-partisan committee to handle the redistricting process.

Hogan called the state’s current partisan redistricting process “disgraceful” and lambasted the legislature for not acting to implement reforms.

Hogan has made passage of the Redistricting Reform Act of 2017 one of his primary goals ahead of the 2018 gubernatorial election. The governor wants to remove lawmakers’ power over redistricting and hand the process over to an independent commission.

Such reforms are strongly opposed by Democrats, who owe some of their dominance in state politics to the party’s power to favor itself when drawing legislative districts.

However, Hogan acknowledged that gerrymandering is common across the country, by both Democrats and Republicans in states where they control the process. Maryland Democrats often cite gerrymandering in other states as a reason for not changing the process in Maryland, as doing so would hurt Democrats at the national level.

Gerrymandering works by spreading friendly voters out to get a simple majority in as many voting districts as possible, and concentrating opposition voters into as few districts as possible.

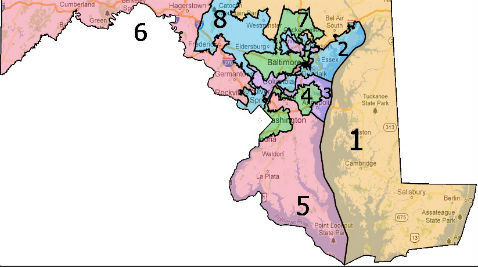

Maryland is considered to be among the most gerrymandered states in the nation. About two-thirds of the state’s registered voters are Democrats, and nearly a third are Republican, yet both U.S. senators and seven of Maryland’s eight U.S. representatives are from the Democratic Party.

The winner-take-all method of determining electoral victory in the United States means that it is far better for a party to be able to win 55 percent of the vote in 10 elections than for it to be able to win 99 percent of the vote in five elections, even if the total number of votes cast is the same. This principle is part of what enabled Donald Trump to win the presidency in 2016; more votes were cast for Hillary Clinton, but they were concentrated in too few states.

Hogan gained an unlikely ally in his push to address gerrymandering when his predecessor, former Gov. Martin O’Malley, D, has recently come out in support of ending the practice.

State Senate President Thomas V. “Mike” Miller Jr., D-Calvert, Charles and Prince George’s, told the University of Maryland’s Capital News Service that he thinks the proposal “is largely politics on the part of the governor, he sees his numbers dropping and he knows this is popular with the people.”

A Democrat-sponsored bill is currently moving through the legislature that would move the state to an independent redistricting process only if New York, New Jersey, Virginia, Pennsylvania and North Carolina pass similar reforms by the end of 2020.

One of the major obstacles to independent redistricting, in Maryland and elsewhere, is the dominant party’s fear that leveling the playing field will put their national party at a disadvantage to their opposition elected from still-gerrymandered states.

The five states mentioned in the Democrats’ bill and Maryland currently send a total of 44 Republicans and 43 Democrats to the U.S. House of Representatives.

The idea is that this nearly even split makes it less likely that reform will give either party an immediate advantage at the national level. The dominant parties in those states would surrender the advantage that partisan redistricting gives them in exchange for neutralizing that advantage in another state where their party is in the opposition.

Alexander Williams, a former judge, spoke in support of reform at the Friday press conference, saying that cases challenging gerrymandered maps are creating a “litigious mess” in the courts. He predicts that courts are going to start imposing their own solutions to the problem, which he worries judges are not capable of doing effectively.

Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said of pornography in 1964, “I know it when I see it.” Likewise, gerrymandering is easy to spot but extremely difficult to prove.

The practice often produces odd-looking voting districts that squiggle around established population and geographic boundaries.

The Supreme Court has acknowledged that partisan gerrymandering could be so extreme in certain cases that it might violate the equal representation clause of the Constitution. The problem is that the Court has yet to find a reliable test to determine how much gerrymandering is too much.

The Supreme Court is expected to take another look at gerrymandering in 2017. In 2016, Wisconsin’s state assembly maps were ruled unconstitutionally gerrymandered. The case relies on the results of the 2012 and 2014 elections, where Democrats won the majority of the statewide general assembly vote, but Republicans still won 60 of the 99 seats in the assembly. That case has been appealed and is scheduled to be heard by the Supreme Court in 2017.