ANNAPOLIS, Maryland – Despite Maryland’s apparent prosperity, the state has a perennial budget problem.

Maryland is in the top 10 for average annual wage and an unemployment rate a half-percent below the national average.

But it also has a structural deficit expected to reach $1.2 billion by fiscal year 2022.

And on Thursday, the state’s Board of Revenue Estimates announced that their projections for the current fiscal year have been reduced by $35.32 million — from about $16.62 billion to nearly $16.59 billion.

Board of Revenue Estimates Director Andrew M. Schaufele said some taxpayers may have shifted any income they could to later tax years to take advantage of lower federal taxes promised by the Trump Administration and the Republican-controlled Congress.

If so, Maryland would see a decline in reported income in fiscal year 2017, but a corresponding increase in reported income in 2018.

The board on Thursday also indicated long-term challenges presented by the federal government’s hiring freeze, which will eventually mean fewer jobs, lower total wages, and less spending in Maryland — all of which contribute to a decline in revenue.

But no one can seem to completely agree on what is causing the perennial problem.

Some believe that mandated spending is the primary issue for the budgetary problems, while others argue that lagging state revenues are causing the issues.

Senate Budget and Taxation Committee Vice Chair Sen. Richard Madaleno Jr., D-Montgomery, said he believes the problem is a combination of “generous” projections in the way state spending is calculated, and underperforming state revenues.

Maryland Secretary of Budget and Management David Brinkley contends that legislative mandates have pushed spending too high, to the point where spending growth is outpacing revenue growth.

These mandates — spending that is written into law by legislators — must be included in all future budgets proposed by the governor.

Brinkley and Gov. Larry Hogan, a Republican, argue that Maryland’s increasingly expensive mandated spending — created in large part by the Democrat-controlled legislature — is a key contributor to the structural deficit.

Currently, Maryland’s revenues are increasing at a rate of 3 percent annually, a number that Brinkley said “would be the envy of all states.”

But mandated spending is growing at a rate of between 4 and 5 percent each year.

“The problem is when we have statutory requirements that say spending shall go up (at a rate higher than revenue growth),” Brinkley told the University of Maryland’s Capital News Service. “That gap is the structural gap.”

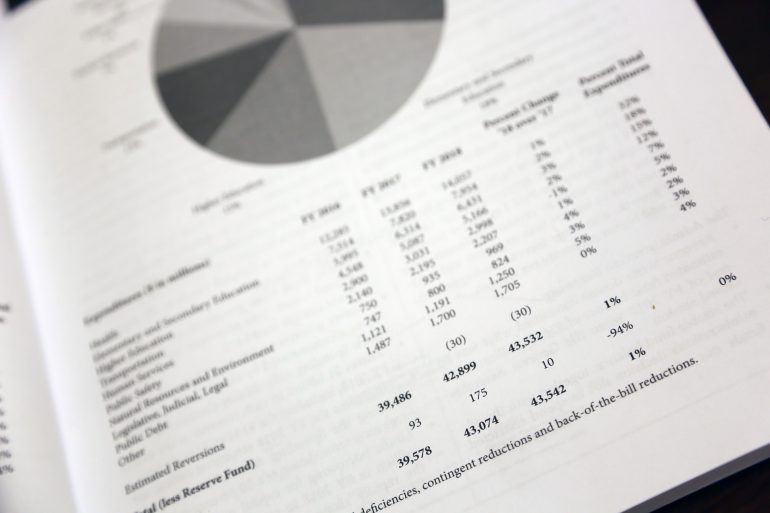

About 83 percent of Maryland’s annual budget is set aside for mandated spending or entitlement programs.

If everything that required funding could be included in that 83 percent, there would be no issues. But the rest of the budget “is not mandated but still might be very attractive” to spend, Brinkley said.

Money from this unmandated 17 percent, over which the governor has more control, is spent in areas such as public safety, university funding and state police.

“Maryland’s budget ballooned by 39 percent in just 10 years due in large part to mandated spending,” said Christopher B. Summers, the president of the Maryland Public Policy Institute, in a January press release. “As a result, our state government has accumulated nearly $2,900 in debt per every Maryland resident. We encourage Maryland legislators to turn off autopilot and exercise greater discretion over taxpayer money.”

The institute said one fix would be to align mandatory spending with revenue increases, so if revenue increases by 2 percent, mandated spending can only increase by 2 percent.

The institute also supports “a policy in which any new mandatory expenditure must be countered with a repeal or reduction of existing mandates.”

“It’s a decent thing for the governor to have some discretion, in things he’d like to be able to do,” Brinkley said. “So that’s our challenge.”

Madaleno agreed that some of the projected spending has been “generous,” such as assuming each state employee gets an annual raise, but said that wasn’t the only problem.

One problem both sides seems to agree on is the way that tax revenues are projected and included in the state’s budget.

“Our ongoing expenditures are greater than our ongoing revenue the last, close to, decade,” said Sen. Edward Kasemeyer, D-Howard and Baltimore counties.

Last fiscal year, the Board of Revenue Estimates projected a modest surplus; however, in September 2016, the board announced that those predictions had fallen $250 million short of actual revenues, putting the state in a hole.

Lawmakers are “used to that now,” said Sen. Roger Manno, D-Montgomery.

They are told they have “x dollars,” and spend “x minus 10” when in reality the amount of revenue is “way south of what we’ve been told,” he said.

Projecting tax revenue is notoriously difficult, Madaleno said. He has heard it compared to driving a car using only the rear-view mirror, and projections are often incorrect.

Tax from income other than wages — such as capital gains and dividend income — has been targeted as a key contributor to the state’s budget problems.

Projecting non-wage income tax revenues is difficult because they are extremely volatile. This volatility is caused by a small percentage of the state’s population paying a majority of these taxes.

The top 1 percent of the state’s population pays between 68 and 73 percent of the extremely volatile non-wage income taxes annually, Brinkley said.

Additionally, under the state’s progressive tax structure, the top 1 percent of the state’s population pays about 21 percent of all income taxes.

Maryland is one of 10 to 15 states where high-income earners play a major role in the outcome of state tax collections, according to Arturo Perez, a fiscal analyst with the National Conference of State Legislatures. As a result, revenues in these states can be more susceptible to stock market forces.

Two bills, heard by the Senate Budget and Taxation Committee in February, present similar plans to protect Maryland from overestimating these mercurial revenue sources.

Both bills try to “smooth out peaks and valleys,” by essentially taking this unpredictable revenue off of the table for revenue projections.

Democrat lawmakers and the Republican administration of Gov. Larry Hogan each proposed bills, and the two are largely similar.

The primary difference is their treatment of the state’s “rainy day” fund, which is where the state places surplus money after balancing the budget.

Under current law, if the fund totals less than 7.5 percent of general fund revenue, $50 million is deposited into the fund. If the fund is at less than 3 percent of revenue, $100 million is deposited into the fund.

Under the Democrats’ bill, proposed by Manno, the $50 million would be deposited if the fund is less than 10 percent of the revenues for a given year.

“The hope is that we will have additional money at the end of that year,” Manno said. The goal is to “build a robust and solvent ‘rainy day’ fund.”

After the “rainy day” fund reaches 10 percent, any surplus money would then go to “underfunded priorities.”

Manno’s bill would also change the way Maryland builds budgets and funds all critical projects, he said.

Hogan’s bill would require the money that is taken off the table be spent on “one-time things,” which will not later count on volatile revenue as a steady funding source, Brinkley said.

To do this, the bill would establish a Fiscal Responsibility Fund. The money can be used for things like pay-as-you-go capital projects and pension funds.

Money would only be placed in the Fiscal Responsibility Fund if the balance of the “rainy day” fund exceeds 10 percent of revenue.

If the balance does not exceed 10 percent, any extra revenue must be placed in the “rainy day” fund.

Had the cap proposed by both bills been in place last year, the state would have been at a $6 million surplus after the session, state analysts said.

Kasemeyer has assigned both bills to a work group that will take the best parts of each, he said.

The group will then amend one of the bills to provide the best solution for the legislature and the state.

Although Madaleno said he does not know which bill he expects to receive a favorable report from the committee, he, Kasemeyer and many other prominent Democrats, including Senate President Thomas V. “Mike” Miller Jr. D-Calvert, Charles and Prince George’s, are cosponsors of Manno’s bill.

Both bills this week were still being studied by the work group, but lawmakers indicated that some version of the legislation is likely to pass this session.

–Capital News Service correspondent Jacob Taylor contributed to this report.