SILVER SPRING, Maryland – Beginning in the mid-1970s, war and political turbulence led a large number of Ethiopians to flee their home country. Many of these emigrants came to the United States, with a particularly high number settling in the Washington region.

Thanks to a welcoming environment and local educational institutions, as well as legislation over the decades that eased immigrant entry into the United States, many Ethiopians were eager and able to stay in the area and put down roots.

“This area became a hub for Ethiopians,” Dr. Getachew Metaferia, an Ethiopian native and professor of political science at Morgan State University, told Capital News Service. “They contributed to the dynamics of multiculturalism.”

As this community has grown, it has infused within local neighborhoods vestiges of native Ethiopian culture, from music to language to art. Montgomery County even has a sister city in Ethiopia, the ancient former royal city of Gondar.

Perhaps the most prominent contribution of Ethiopian immigrants to the Washington area, though, has been food.

“A night out at an Ethiopian restaurant is as much a tradition here as an outing to a deep-dish pizzeria might be in Chicago,” Jessica Sidman wrote in Washingtonian magazine in January.

Today, Ethiopian communities – and thus, restaurants – have spread from their traditional neighborhoods within the District of Columbia (Adams Morgan, Columbia Heights and, more recently, Shaw) to several of Washington’s suburbs, most notably Silver Spring.

Here, Ethiopian cuisine has become a defining food staple, even in one of Maryland’s most ethnically diverse suburbs on the edge of the nation’s capital. (Thirty-four percent of Montgomery County, where Silver Spring is located, is foreign born, according to a Capital News Service analysis).

Along the main blocks of Georgia Avenue and Fenton Street are dozens of Ethiopian restaurants, nestled among Chinese, French, Greek, Italian and other international dining options.

For some Ethiopian restaurant owners, it was the success of existing establishments that prompted them to start their own businesses in Silver Spring.

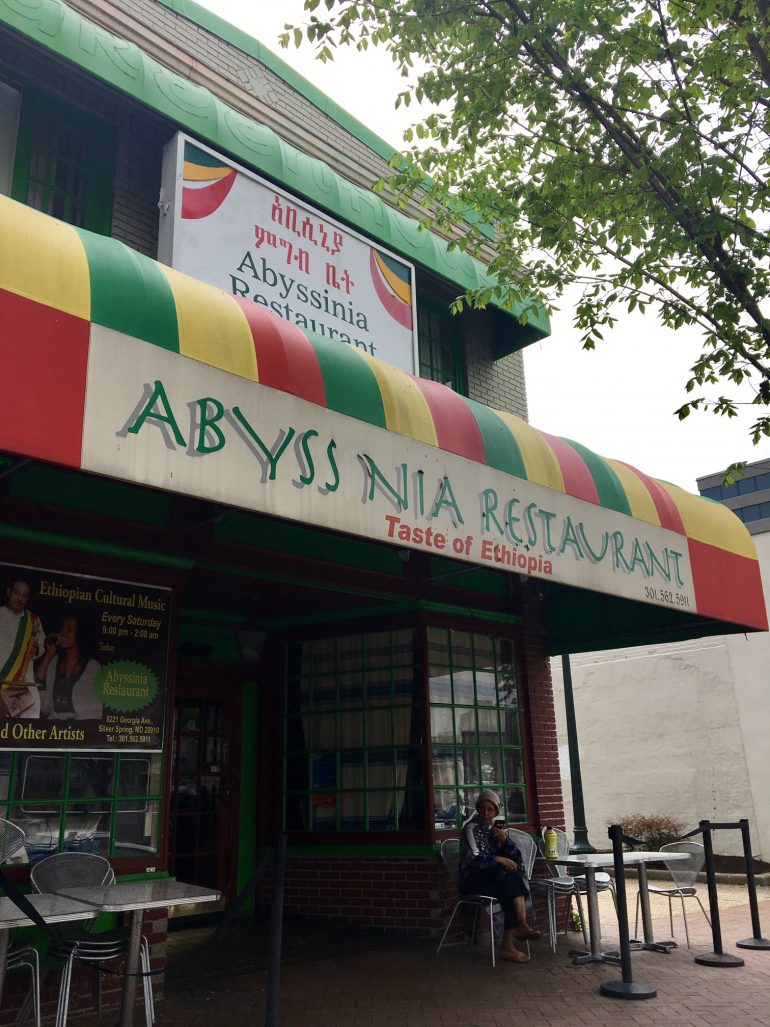

Solomon Abdella owns and manages Abyssinia Restaurant on Georgia Avenue. “I saw some Ethiopian restaurants being successful,” Abdella told Capital News Service. “(My wife and I) wanted to try it.”

Now in its eighth year, Abyssinia has established itself as a comfortable, family-run business serving up authentic Ethiopian dishes: primarily vegetables and meat paired with injera, the traditional, pancake-like Ethiopian bread that comes with most meals.

Despite the restaurant’s success so far, Abdella thinks achieving long-term staying power will depend on how well Abyssinia is able to cater equally to both Ethiopian and non-Ethiopian customers.

“If your business (serves) 50 percent Ethiopians and 50 percent Americans, you’ll be successful,” he said. “We’re going towards that.”

One way Abyssinia is trying to appeal to non-Ethiopian diners is by offering more familiar American food options alongside native Ethiopian dishes. For example, with any meal, customers can substitute spaghetti or rice for the usual injera.

It’s part of a growing trend of cultural fusion among Ethiopian restaurants in Silver Spring. In addition to traditional lunch and dinner places like Abyssinia and others, more and more alternative, Americanized Ethiopian eateries – from coffee shops to fast-food restaurants – are popping up in the area.

In addition, the Ethiopian Community Center in Maryland hosts an annual Ethiopian Day Festival each summer, which gives participants a taste of Ethiopian culture through food, live music, dancing, comedy and more.

For Abdella, who has lived in the United States since 1981, the rising interest from people of all backgrounds in Ethiopian culture is reflective of the welcoming, stable community he’s found in Silver Spring.

“There are a lot of Americans and a lot of Ethiopians,” he said. “I have a very good connection with the community.”

When the first wave of Ethiopians started coming to the United States, however, most didn’t intend to stay. Before the surge of Ethiopian immigration in the 1970s, an earlier group arrived in the 1950s – but only to study.

After World War II, then-Emperor Haile Selassie began sending promising Ethiopian intellectuals to the United States for their educations, Metaferia said. Washington’s Howard University, in particular, emerged as a social and intellectual hub free of discrimination.

“Howard University, because of its history, had open arms for people of color,” Metaferia said, adding that the historically black university embraced the notion of pan-Africanism (the idea of commonalities among all people of African descent).

Still, most of these students planned to return to Ethiopia afterwards, Metaferia said. The goal, he said, was for the country’s brightest young minds to gather knowledge abroad, then return home with the aim to make Ethiopia stable and prosperous state.

“Immigration was not in the DNA of Ethiopians,” he explained. “They just wanted to work in their country and help build the nation.”

But things changed in 1974, when a brutal military dictatorship seized power in Ethiopia.

“There were gross human rights abuses,” said Metaferia, who himself arrived in the country to study at Howard in 1977. Intellectuals and others who didn’t support the new socialist government were persecuted, he said.

Within the United States, Washington became the primary destination to settle, thanks to this existing intellectual hub and the then-African American majority in the district – factors that allowed Ethiopians to feel less threatened by racial discrimination, Metaferia said.

A sense of community and belonging is evident when dining at a restaurant like Abyssinia. Although owners like Abdella are working to cater to Americans as well, these restaurants also serve as a unique place for Ethiopians to discuss things like politics, Metaferia said.

“These restaurants do not only provide food,” he explained. “They’ve become, also, a focal point where Ethiopians congregate and discuss about their country.”

But Metaferia thinks these conversations could be more focused on American government and politics, given recent U.S. policies toward immigrants.

As Ethiopia continues to suffer political turmoil under dictatorial rule, the Trump administration’s America-first agenda is making the United States a less and less appealing destination for Ethiopians looking to leave their home country, Metaferia said.

Meanwhile in Silver Spring, there have been more immediate concerns regarding attitudes toward immigrants.

Some said they’ve noticed a change in racial attitudes since the election of Donald Trump last November.

“To be honest, people are afraid,” Seble Lemme, chef and co-owner of Lucy Ethiopian Restaurant, told the International Business Times in January.

In the days following Trump’s election, at least two Silver Spring churches were vandalized with pro-Trump, anti-minority messages, according to the International Business Times. (One of the churches was heavily attended by immigrants; the other had a mostly white congregation, but was a prominent supporter of liberal movements such as Black Lives Matter and LGBTQ issues.)

Still, many in Montgomery County have shown support for immigrants and minorities in the wake of Trump’s election. A number of local high school students, for example, participated in walkouts protesting the rhetoric of the new administration.

And for Abdella and many other Ethiopians, Silver Spring and Montgomery County remain a permanent and appealing place to live.

“I’ve been here more than I’ve been back home (to Ethiopia),” Abdella said. “Silver Spring is my home.”