SILVER SPRING, Maryland ––– Step into Edwin Amaya’s fifth-grade math class at Kemp Mill Elementary School and you may find yourself overwhelmed, a la “Are You Smarter Than a Fifth Grader?”

It likely won’t be the mathematics that gives you trouble, but the language – unless you speak Spanish.

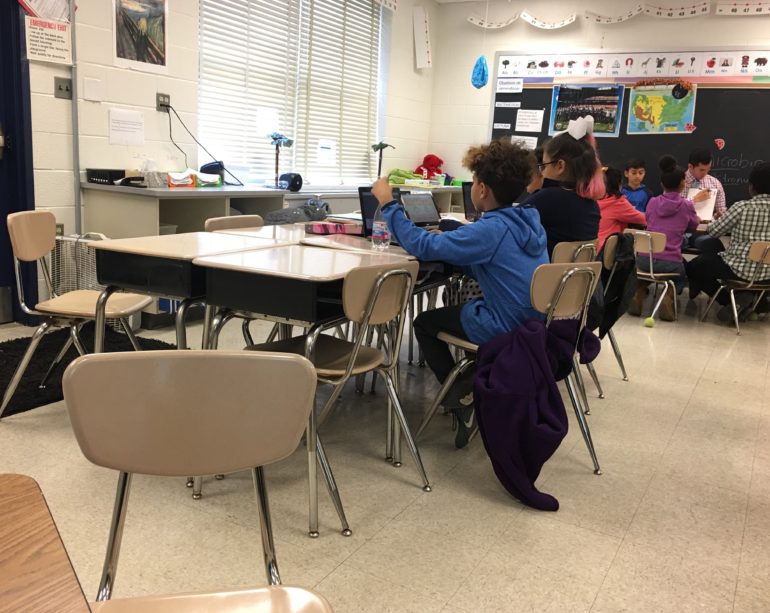

Amaya’s students are in the midst of a “Spanish week,” in which they are required to speak the language all day, every day. In Thursday’s class, a small group is instructed at a round table as the others stroll around the room, solving problems taped to objects – a math scavenger hunt, if you will.

Since 2001, Kemp Mill has offered dual-language education in English and Spanish. Students enrolled in that program receive half of their instruction in English and half in Spanish.

The language of choice alternates by week, but is limited to language arts, math, science and social studies classes. All special classes – physical education, art, music and STEM – are taught only in English.

Until fall 2016, the dual-language education was an optional enrichment program.

For the past two years, however, the school has been in the process of requiring the program for its entire student body.

Last fall, all kindergartners were required to take English-Spanish classes, and this year, first graders joined that cluster as well. Subsequent grades will be added each year until the entire school’s curriculum is taught in English and Spanish for the 2021-22 school year.

Although Kemp Mill is one of three Montgomery County public schools with dual-language education, it is the only school that offers it for all students.

Amaya teaches his fifth-grade students sixth-grade level math, in both English and Spanish, but his students have much bigger aspirations than being in the advanced math group.

Quenia, for example, translates for her El Salvadorian mother who doesn’t speak English, which makes her feel “lucky.”

Quenia wants to be a soldier when she grows up because of the opportunities she’s been afforded.

Dual-language education, she says, has given her a glimpse of some of the sacrifices she’ll be making in the military. She explains how her mother offers to take her out for ice cream and to a local park, but she often must stay home, instead opting to work to have a better grasp of English and Spanish.

“¿Qué pasa si hago esto?” Quenia dreams. (“What would happen if I did that?”)

“This country has given me food, it’s given me clothes, it’s given me life,” Quenia explains. “And I want to fight for this country.”

Her classmate Daniela, an 11-year old who also speaks Spanish at home, wants to be a lawyer to help those who have been wrongly imprisoned due to language barriers. She says she wants to learn French in middle school, so that she can talk to even more of her peers.

Daniela has even noticed connections to French, given her English-Spanish background.

“We have a French student in our class, who came last year and it was a hard time for him to communicate,” Daniela says. “He’s learning a lot in English and Spanish. We all helped him, and he’s learned a lot of things.”

There are 19 students in Amaya’s class and according to school administrators, no class exceeds 22. Amaya asserts that the smaller classes allow for a more intimate and compassionate environment – one in which the students are encouraged to help one another acquire secondary language skills.

“This develops these students socially,” Amaya says. “It’s tighter-knit when you’re in dual language.”

“I feel proud not just of their hard work, but for them to be thinking about that: helping others,” Amaya says with a smile.

Principal Bernard James echoed Amaya’s sentiment, calling the program “a gift.”

“We’re preparing our students to be advocates for themselves, their families, others,” James said. “Our world goes far beyond Montgomery County and we’re preparing them to take it, to seize it.”

James feels that this “50-50” English-Spanish divide is the best way to bridge the achievement and opportunity gaps.

“We have students from all over, so we really look to see if our potential staff are those who can come in and make an authentic connection,” James says. “Children can tell whether or not you’re authentic.”

As of last year, Kemp Mill’s student body was 75 percent Hispanic. That contrasts to Montgomery County Public Schools system-wide, which are 30 percent Hispanic.

James bedphasizes the significance of having teachers who are culturally competent and reflect their classroom’s demographic.

“We’re preparing our students to be advocates for themselves, their families, others,” James says. “We shouldn’t be so prideful to think that the only language that matters is English.”

Several of Amaya’s students understand that, the math teacher asserts.

He tells of a student who just arrived from Mexico who doesn’t speak English. His peers have helped him access the class’s online materials and showed him how to line up in between class periods and where to put his backpack.

“This is an amazing program,” Amaya says. “It’s absolutely humbling to be a part of it.”