ANNAPOLIS, Maryland — On July 27, 2005, two children found human remains near a wooded area in southern Baltimore. The Anne Arundel County Police secured the scene and the remains were described as a 19- to 23-year old female, roughly 5-feet-5 to 5-feet-8 inches tall with dark red or brown curly hair.

But they couldn’t predict what her face may have looked like, until recently.

A new technology can take any DNA sample from a crime scene – from a drop of blood to bone tissue – and read tens of thousands of genetic variants to predict a facial image. It’s called Snapshot.

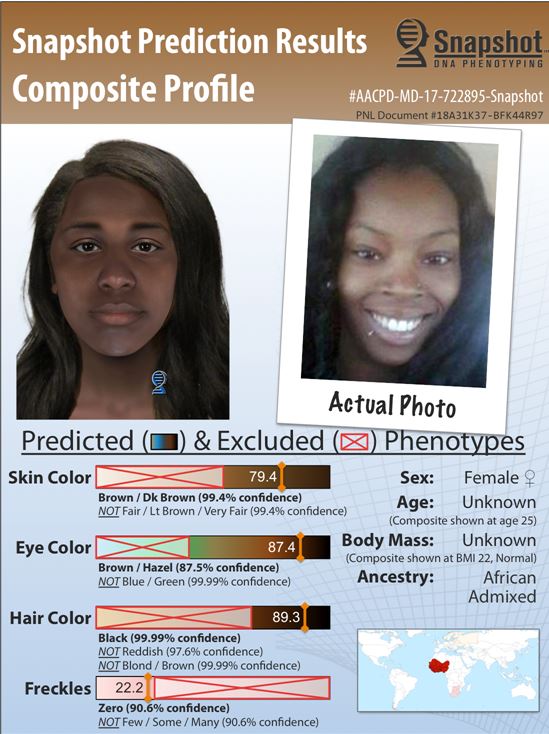

Through a computer-based 3D algorithm, Snapshot can predict ancestry, eye color, hair color, skin color, freckling and face shape.

A few Maryland law enforcement agencies have said that, in cases where there are no witnesses, it’s helped narrow down investigations into potential suspects and victims.

“Results can provide a general direction for investigators to look into,” said Darren Francke, director of the Montgomery County Police Department’s Major Crimes Division. “It can also serve to jar the memory of citizens so they come forward and provide information they would have otherwise disregarded.”

Snapshot was launched in January 2015 by Parabon NanoLabs, a Virginia-based DNA phenotyping company that assists law enforcement organizations. Phenotyping is the process of predicting physical appearance and ancestry from DNA.

The service costs between $3,600 and $4,700, said Ellen Greytak, director of bioinformatics at Parabon. It varies based on whether the extracted DNA sample is pristine or a mix that requires more lab equipment to evaluate.

There have been six public cases in which Parabon has partnered with a Maryland law enforcement agency since 2016. But law enforcement officials and the company confirmed to Capital News Service that there have been more investigations that remain confidential.

Of the six cases in Maryland where Parabon has posted the Snapshot image on its website, one has already resulted in a murder charge. That investigation started in the fall of 2017, when police found remains in Glen Burnie.

After early efforts to identify the skeletal remains failed, the Anne Arundel County Police contacted Parabon. Snapshot’s analysis of the DNA showed the victim was of African-American ancestry, with brown to dark brown skin, brown eyes, black hair, and no freckles.

A certified forensic artist at Parabon performed a facial reconstruction from the victim’s skull – not all unidentified-person cases have a skull – and digitally combined it with the DNA predictions to show an image of how the victim may have looked when she was alive.

The Baltimore City Police Department then contacted the Anne Arundel County chief, as there were several similarities between the Glen Burnie victim and a Baltimore missing person. Police were able to identify the victim in November as Shaquana Marie Caldwell. And in January of 2018, they charged her boyfriend, Taras Caldwell – who had the same last name but was not married to the victim – with murder in connection with her death.

“The use of that technology revealed the body,” said Maj. Marc Limansky, a spokesman for the Anne Arundel County Police Department. “Investigators are extremely confident this technology will increase the solvability of many cases to come.”

Some, however, are skeptical of the science behind Snapshot and fear there could be unfair consequences brought by an inaccurate prediction.

“When you put out something that isn’t based on peer-reviewed science, there are a lot of pitfalls,” said Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst at the American Civil Liberties Union. “It can feed into a racial bias, waste people’s time, and be used to justify searches of (innocent) people.

Benedikt Hallgrimson, the head of cell biology and anatomy at the University of Calgary, agreed with that assessment. Hallgrimsson said other things unrelated to DNA, like age and sex, could be making the images similar but that results are not definitive enough to predict a face without having the skull.

He’s concerned that unfounded predictions and over-promising could undermine the public’s trust in science.

“Science is a foundation of economic and social progress in many ways,” Hallgrimsson told Capital News Service last week.

In a statement, Parabon, which considers Snapshot to be similar to that of an eye-witness or a surveillance camera, responded to the concern over the new tool’s legitimacy.

“We carefully instruct investigators on how to best use the information Snapshot provides and how it should not be used,” Parabon told CNS. “By excluding a large proportion of potential suspects, Snapshot actually saves people’s time and reduces the number of innocent people who would otherwise need to be investigated before being excluded.”