It was 5 a.m. when Geoff Britten grabbed the thick red rope that hung from the top of the metal structure that was Mt. Midoriyama, his eyes looking skyward at the prize. He had been competing all evening, and the night had finally reached its climax.

The instructions were simple: climb the rope to the top of the mountain and Britten, of Olney, Maryland, would be the first American to complete all four stages on NBC’s American version of the popular Japanese obstacle course, “Ninja Warrior.” The only problem was that he had to climb the 75-foot long rope in just 30 seconds.

Britten, then 36, hit the buzzer at the top of the mountain with less than a second left on the clock.

“It was definitely something that was very important to me,” Britten, who completed Stage Four in his second season, told Capital News Service. “I trained really hard that year for it. I almost had a feeling I was going to do it.”

Britten was denied winning the $1 million prize when Isaac Caldiero, the only other competitor to reach Stage Four in Season 7, reached the buzzer faster. Still, it was a unique accomplishment for Britten, a former cameraman. And like climbing Mt. Midoriyama, the weeks and months after Britten’s achievement were unfamiliar territory.

“Ninja Warrior” athletes, also known as ninjas, experience the success and attention from appearing on the American version of the show in different ways, and the way they handle it varies.

Ninja hopefuls send in submission videos and line up for weeks to participate in the show’s city qualifiers. The competitors who make the cut advance to the city finals and then the national finals in Las Vegas.

Many of the contestants who make one or two appearances on the show return home to a few claps on the back and conversations with friends. Some of the more popular ninjas who regularly return to compete make it an integral part of their lives.

For Britten, being the center of attention was an adjustment. He had to deal with consistent recognition from fans of the show congratulating him and wanting to talk. Eventually, it escalated to the point where being out in public became a hindrance.

“It’s very hard to be that person,” Britten said. “I’m not someone who ever wanted to be famous or be in the spotlight. I accept it, I deal with it well. But it’s not something I seek out actively.”

While Britten announced he was taking time off from competing after Season 8, he wasn’t completely done with “Ninja Warrior.” Shortly after his announcement, ATS, the company that builds the obstacle courses seen on the show for NBC, reached out to Britten wanting him to be a tester. His background in television and obstacle courses created a good fit.

“That was a whole other world to me, and I really enjoyed it,” Britten said. “I got to work with the producers on obstacle difficulty, trying to make the courses doable for a certain amount of people. I think I was a huge asset for them that year.”

Now, Britten is expanding his knowledge of the sport while also making it more accessible. Working with current and former ninjas, Britten helped start Ninja Nation, a company dedicated to building gyms for ninja hopefuls of all ages.

“Our goal is to build 100 gyms,” Britten said. “We’re just trying to expand access to this growing sport. It’s grown into having multiple leagues, multiple tours. We want to create a professional environment where parents feel safe bringing their kids.”

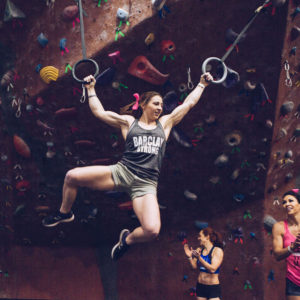

The expansion of the sport has allowed athletes like former gymnast Barclay Stockett, of Dayton, Texas, to thrive after their former athletic careers end. Prior to making her “American Ninja Warrior” debut in Season 8, Stockett participated in Team Ninja Warrior — a relay version of the obstacle course — where she found the community she had been searching for since competing in gymnastics.

“I found my new sense of place,” Stockett said in a CNS interview. “When I quit gymnastics in my senior year of high school, I felt like my athletic career was over. It was like I was in a season of mourning, and it took a long time to find my identity as a person without being an athlete. By the time I found Ninja Warrior…I was really in a healthy mindset to try something new.”

Stockett was well known in the ninja community before appearing on the show, but she skyrocketed in popularity after Season 9. It’s still a new experience for her, especially when she gets recognized in unlikely places.

“I was in front of the Louvre (in Paris)…and this couple came up to me and said, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re Barclay Stockett,’” she said. “They knew my name, and I was completely blown away by that.”

Since April of 2017, Stockett has been working alongside the U.S. Air Force for Alpha Warrior, a company that provides obstacle-based training to branches of the U.S. military. Her work has taken her to “around 30 bases” across the world, including in Italy, Germany and South Korea.

“It was so cool because whenever I was looking for something different…I was praying that I would find a job that allowed me to travel, involved a little less time working and allowed athletics and ninja (training) if possible,” she said.

For others who compete in “American Ninja Warrior,” like Bethesda, Maryland, sprint canoeist Gavin Ross, success on the course doesn’t lead to new careers or inspire them to expand the sport. But it does give them a unique experience that adds to their training for other sports.

Ross had been a fan of Ninja Warrior since it debuted in Japan before coming to the United States, and competing was always something he wanted to do. But because there weren’t a lot of ninja gyms near him, he wasn’t able to train as much as expected.

“When I found out I was going to compete (in the qualifying course), I didn’t do much training specific to ninja for that,” Ross told CNS. “I just started paddling again and started working on my grip strength.”

Ross added pull ups and dead hangs to his workout. He also placed pool noodles on the bars and handles in the gym that made him work harder to close his hands. But when Ross qualified to compete in Las Vegas for the national finals, he made weekly trips to ninja gyms.

Ross is a new face to many fans of the show, so he isn’t as recognizable as much as Britten or Stockett yet. He often gets contacted by old high school friends who knew how much he loved the sport. But he does get approached by strangers from time to time who say they know him.

“There were a few people who I had no idea who they were,” Ross said with a laugh. “So I just had to act like I did. They were calling me by name, and when that happen you just assume you’ve met them before.”

Regardless of the level of success ninjas experience from the show, many believe it is a rewarding part of their lives.

Britten was reminded of that after failing on Stage One in Season 8. He emerged from the water with a smile on his face and said two words: “Everybody falls.” He received more than 1,000 letters from parents thanking him for what he said.

“I got more kudos falling with grace than I did doing well with style,” Britten said. “I thought it was indicative of why ‘Ninja Warrior’ is so great. People look at it as a physical challenge, but it’s also a role model and great teacher.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.