ANNAPOLIS, Maryland — Seven days after President Donald Trump was inaugurated, he signed a controversial executive order blocking refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States.

Hundreds of people were detained and thousands of visas were revoked as part of what became known as the Muslim ban.

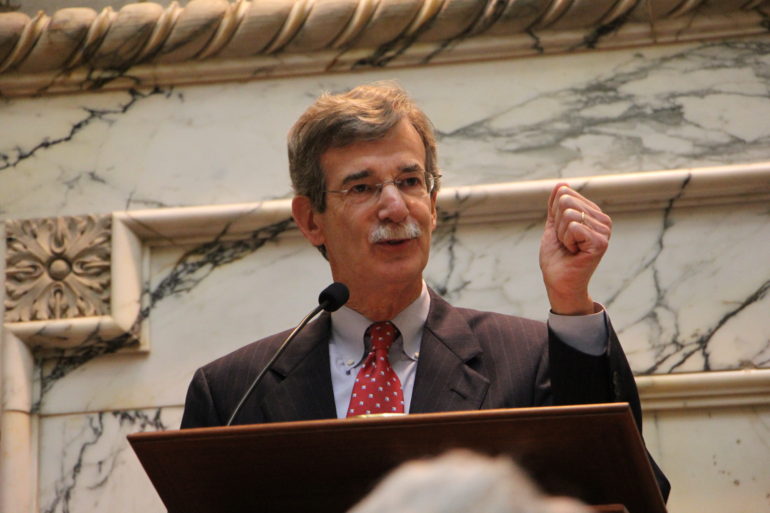

In response, on Feb. 1, 2017, Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh, a Democrat, requested permission from Republican Gov. Larry Hogan to challenge the constitutionality of the order.

Hogan did not respond to Frosh’s request.

Two weeks after the request, the Democrat-controlled Maryland General Assembly passed a joint resolution, called the Maryland Defense Act of 2017, granting Frosh expansive authority to file lawsuits against the federal government without prior approval from either the governor or the state Legislature.

It went into effect immediately, on Feb. 15, 2017.

On March 13, 2017, Frosh joined a coalition of 12 other states and Washington, D.C., in a lawsuit against the Homeland Security and State departments challenging the immigration ban.

This marked the first time in more than 150 years that a Maryland attorney general unilaterally joined a lawsuit against the federal government — a power Frosh has revisited about 20 times since that day.

‘It is long overdue’

Some legal experts see Frosh’s expanded authority as Maryland simply catching up to other states, said former Maine Attorney General Jim Tierney, a Democrat who served from 1980 to 1990. Tierney has been a proponent of broad legal autonomy for the attorney general since his time in office.

“It is long overdue,” said Tierney, who teaches law at Harvard and Yale. “The office of the attorney general is there to represent the public interest. … That’s why the office exists.”

Since 1864, when the office of the attorney general was reestablished in the Maryland Constitution, state law had required the law officer to get permission from the governor or state Legislature to file litigation. With the passage of the Maryland Defense Act, the state joined more than 40 other states and Washington, D.C., in allowing their attorneys general to file lawsuits independently.

“Democracy works better when state attorneys general have the ability to keep the federal government obeying the law,” Tierney said. “If the AGs can’t do it, no one else can.”

Backlash

The Maryland Defense Act passed along party lines in the House of Delegates. In the Maryland Senate, three Democrats voted against it.

One of those Democrats, James Mathias, D-Somerset, Wicomico and Worcester, said he opposed the measure because of the speed with which it was passed.

“In the 12 years I’ve been in the General Assembly, I’ve never heard of it as a concern,”

Mathias said. “Then it was an immediate concern and had to be acted on now. … The immediacy of it was more created than real.”

Mathias is facing a stiff challenge from Republican Mary Beth Carozza in Maryland’s 38th state Senate district, which went to Hogan in 2014.

Frosh defended the measure in an interview with Capital News Service, calling it “necessary” to combat the Trump administration’s policies, which he called “unconstitutional” and “threatening to Maryland.”

“It was pretty obvious … that Maryland’s interests were affected by what was going on in D.C. — and affected adversely,” Frosh said.

Hogan initially criticized Frosh’s powers, as it effectively cut him out of any legal decisions made by the Maryland attorney general’s office. On “The C4 Show” on WBAL radio in February 2017, Hogan called the resolution “outrageous” and “disgraceful,” and the “lowest point of the Legislature.”

Mending fences

Despite his protestations, the governor has since worked with Frosh on several legal cases, including two petitions filed in June to the Federal Aviation Authority regarding altered flight patterns over local airports affecting residents, and a lawsuit in September against the EPA concerning air pollution from neighboring states.

“The governor made his objections to the Legislature removing executive branch oversight and making the first change to the Attorney General’s power since the Civil War when they passed this misguided legislation,” said the governor’s communications director, Amelia Chasse, in a statement. “The Hogan administration has … directed the Attorney General to take legal actions to protect our environment, fight the opioid crisis and honor our veterans.”

Last year, Hogan directed Frosh to file an amicus brief against an appeals court that ruled a cross-shaped statue honoring veterans in Prince George’s County was unconstitutional. Frosh did so in August of this year.

The governor also called on Frosh to take legal action against opioid manufacturers and use any settlements to fund addiction-prevention programs.

Frosh declined Hogan’s request, stating that his office for more than two years had been taking part in an investigation into opioid companies and their role in the state’s overdose epidemic.

Frosh said he has a “good functional relationship” with the governor despite their policy disagreements. Under the Maryland Defense Act, Hogan does have an opportunity to voice dissent against a lawsuit filed by the attorney general, but has yet to do so, Frosh said.

“I don’t agree with the General Assembly all the time. I don’t agree with the governor all the time. But we’re lawyers,” Frosh said. “We give them the best advice we can give them. Sometimes they take it, sometimes they don’t.”

Litigation

In the 18 months since Frosh was granted his new authority, his office has led or joined more than 20 lawsuits against the Trump administration on issues ranging from suing to protect the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals immigration policy, to investigating whether Trump has benefited financially from foreign governments, an act forbidden under the Constitution’s emoluments clause.

Litigation to protect the Affordable Care Act, net neutrality and several challenges to the Environmental Protection Agency, and Energy, Education, Health and Human Services and Justice departments have followed.

Craig Wolf, Frosh’s Republican challenger in the general election this fall, said the attorney general is more focused on attacking the Trump administration than addressing issues like gun violence in Baltimore City and the statewide opioid epidemic. Frosh has been investigating opioid manufacturers dating to 2016.

“The attorney general should only bring cases when, No. 1, Maryland’s direct interests are at heart; No. 2, there’s a sound legal base; and No. 3, there’s a chance of success on the merits, on the facts,” Wolf said. “Most of the cases that he’s filed are policy disputes, not legal disputes. They are based upon his feeling that the administration has changed rules that he doesn’t agree with.”

Former Maryland Attorney General Doug Gansler, a Democrat, whom Frosh replaced in 2015 when Gansler unsuccessfully ran for governor of Maryland, offered support for Frosh, calling him “the last line of defense” to protect Maryland’s public interest.

“It’s not Congress standing up to Trump,” Gansler said. “There has to be a check on power and Frosh is it.”’

Frosh has taken particular interest in protecting the state’s environment. Nearly half of the lawsuits are against the Environmental Protection Agency, ranging from properly labeling pesticides and protections against greenhouse gas emissions, to fighting vehicle emissions standards and air pollution control.

Frosh called these lawsuits “critically important” to protecting Maryland’s air, soil and waterways and its people. The EPA has rolled back nearly 50 environmental regulations since Trump took office, according to a rollback tracker maintained by Harvard Law School.

“The Trump administration, instead of addressing or enforcing the rules and laws (protecting the environment) that were put in place by the Obama administration, is not just failing in their duty to do it, they’re refusing to do it, which is a violation of the law,” Frosh said.

In addition to lawsuits, Frosh has submitted amicus briefs – written support of current lawsuits without formally joining – as well as letters and comments to federal departments, pushing back against current government rules or calling for new rules to be implemented.

For example, Frosh last month filed an amicus brief in support of a lawsuit attempting to protect the rollback of certain parts of the Affordable Care Act and another seeking to protect asylum-seekers.

And on Wednesday, Frosh joined a bipartisan coalition of 34 state attorneys general calling for the Federal Communications Commission to establish rules allowing telephone companies to block illegal robocalls to unsuspecting customers.

Legal successes

Frosh and other state attorneys general have also focused on the policies of U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos.

Maryland and 17 other states plus the District sued the Education Department for not enforcing two Obama-era policies regarding student loan repayment.

“(DeVos) is basically standing up for the predatory, for-profit, so-called schools at the expense of the most vulnerable people,” Frosh said. “Thousands of folks in our state have gone into debt and can’t get out of it because they were made promises by these schools that the schools didn’t fulfill.”

In September, a federal judge ruled that DeVos was in violation for not enforcing one of the rules, and the other case is still pending.

Another lawsuit alleged that Trump had violated the Constitution’s emoluments clause, which prohibits the president from benefiting financially from foreign governments through his businesses.

Whether foreign governments are influencing the president’s policies isn’t a question the American people should have to ask, Frosh said.

“The emoluments clause is a way to make sure that the president of the United States is putting our interests first and not his bottom line first,” he said.

The case has moved through the federal court system since it was filed with District of Columbia Attorney General Karl Racine in June 2017. In July, a federal judge declined to dismiss the case despite claims from the president’s attorneys that the case lacked legal standing.

‘You have got to wonder how he’s paying for all of this?’

Frosh’s critics have questioned how the attorney general will pay for the lawyers and hours spent litigating Trump’s policies. The 2017 resolution included $1 million in additional funding for the attorney general’s office to pay for more lawyers. Hogan refused to sign the bill, and used his budgetary powers to withhold the funds.

“When he (Frosh) sought this authority, he said he didn’t need money,” Wolf said. “Then he came back and said he needed $5 million to do it. You have got to wonder how he’s paying for all of this.”

Wolf also said that lawyers from other divisions in the attorney general’s office are being assigned to lawsuits against the federal government.

“He’s robbing Peter to pay Paul,” Wolf said. “He’s using lawyers that would be assigned to other divisions whether it be consumer protection or environmental or securities or whatever it might be.”

This is not the case, Frosh said, adding that his office has received a grant from New York University School of Law’s State Energy & Environmental Impact Center to fund two lawyer positions in his office, and has also received significant pro-bono help from outside law firms.

“I’ve heard criticism for millions we’re wasting, but in fact the cost to the state is negligible,” Frosh said.

Maryland Speaker of the House Michael Busch, who signed the resolution granting Frosh his powers, said additional funding is necessary for the attorney general to continue doing his job. “There’s no sense in giving authority if you aren’t going to provide resources” to carry it out, Busch said in an interview with Capital News Service in September.

Partisan battles

All but one lawsuit Frosh has led or joined since last year has included states with Democratic attorneys general. Colorado and its Democratic governor, John Hickenlooper, joined Frosh and 16 Democrats in suing the Commerce Department and the Census Bureau over a proposal to include a citizenship question on the 2020 census.

The state’s Republican attorney general, Cynthia Coffman, voiced her support in April for the Commerce Department proposal, so the state’s chief legal counsel will represent Colorado in her place.

The partisan divide between states’ attorneys general and the federal government is a recent development, said Todd Eberly, associate professor of political science at St. Mary’s College of Maryland.

Republican attorneys general sued President Obama’s administration over partisan disagreements on DACA and the Affordable Care Act, Eberly said. Now, Democrats are suing the Trump administration in the same way.

Between when Frosh was sworn in on Jan. 6, 2015, and when he was granted more legal authority his office had not filed a lawsuit against the federal government.

“When this trend began … I understood what it was,” Eberly told Capital News Service. “It’s not necessarily driven by questions of good policy but driven by partisan politics. It’s virtually impossible to deny that that’s what’s happening.”

Frosh pushed back on the notion that litigation his office has brought against the Trump administration was due to political disagreements. Every lawsuit he has joined or initiated has been necessary, he said.

“If you look at what happened in the first month of Trump’s presidency, there were a series of actions that were taken (by the president) that were unconstitutional (and) in violation of the law … that just were threatening to Maryland,” Frosh said. “I wouldn’t have filed them if they weren’t important.”

—Capital News Service correspondent Savannah Williams contributed to this report.

You must be logged in to post a comment.