WASHINGTON – Carie Dever-Boaz was ready to step away from coaching college softball when the phone rang.

After spending two years at the University of Virginia as the Cavaliers’ head softball coach, Dever-Boaz was expecting to make the trip back to her home area of Memphis, Tennessee, to spend time with family and put college softball in the background of her 12-year coaching career.

She was not expecting a man named Paul Wilson to give her a call that changed her plans. He was starting a professional women’s softball team called the Washington Glory, and he wanted her to be the head coach.

“I said ‘I am not interested and you can’t afford me,’ jokingly,” Dever-Boaz recalled. “He said, ‘throw out a price,’ so I threw out something I thought was absurd…and he said, ‘OK, it’s a done deal.’”

After talking it over with her family, Dever-Boaz agreed, and in 2007 she and Wilson created one of the hottest teams in the National Pro Fastpitch league.

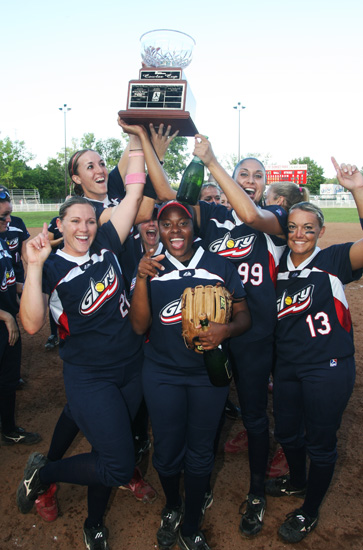

The Glory won the NPF Championship in its first year, finishing 34-10. The roster was riddled with high-profile talent like former University of Tennessee pitcher Monica Abbott and longtime veterans.

On the surface, it appeared as if the team was trending up with no signs of peaking any time soon.

But the success was actually a facade for a cold reality: the team was broke.

“What happened…really was a sad state of affairs,” Dever-Boaz said.

The team was moved from its original home at George Mason University to Westfield Softball Complex in Fairfax County before the 2008 season. Paychecks started to come later and later. And the fan base that regularly filled 500 seats for home games had decreased.

The team made it back to the championship but lost to the Chicago Bandits. Eventually, the team acquired too much debt and folded before the 2009 season.

The players’ contracts were sold to the USSSA Pride and shipped to Florida. Some players, like Abbott, continued to play softball long after their days with the Glory. Others didn’t make it that long and pursued other careers.

But the feeling wasn’t the same. The culture was different, and there are many who were associated with the organization who wish it had ended differently.

“The first season couldn’t be any more than a dream season,” Dever-Boaz said. “But in the last half of the second season, there was so much stress on everyone.”

Strong chemistry and a unique environment

Wilson’s plan for bringing professional softball to the Washington region actually started a year earlier than he anticipated. National Pro Fastpitch wanted to quickly replace a team that had left the league, the Connecticut Braketts, so Wilson was asked to create the Glory by the start of the next season.

The next 45 days were filled with the process of forming the team. Finding a place to play was easy; Wilson struck a deal with GMU, which immediately got to work installing lights and stadium seating at one of its softball fields.

Wilson said he was running at “Mach Three” to get the team going, but he took his time to find the right players.

“I wanted us to be real particular about the types of people the players would be,” Wilson said. “It wasn’t just their physical capability in softball. It was also about who they were and if they were willing to give back to the community.”

Establishing a presence in the community was a common goal for many fastpitch teams, according to former catcher Germaine Fairchild, who had been in the league since 1998 before joining the Glory through a supplemental draft.

At its best, the effort felt a little forced with other teams. But it was different with the Glory, Fairchild said. It actually felt real.

“With other teams, it was just sitting at some tables in a shopping mall,” Fairchild said. “It wasn’t really engaging. The spirit was a little more genuine with the Glory.”

The team hosted regular clinics that offered the chance for younger players to learn from professional players. But the clinics also gave them a chance to build a rapport with the Glory’s players and provided role models in the sport.

“There was no better feeling,” former shortstop Amber Jackson said of working with younger players. “It was so special. You’re now a role model for these kids. It was a great thing for some of them who thought they couldn’t play after college.”

Players were encouraged to interact with the fans, who were highly engaged and interested in the game. Players sat in the stands, rather than the dugout, between innings to create a more personal relationship between athletes and the fan base.

That was exactly what Wilson wanted to do.

“We told the ladies before they even signed a contract that it was important for us to have a fun, family-oriented atmosphere,” Wilson said. “And there were a lot of dedicated fans who were invested in what was happening on the field as well as the ladies’ lives.”

From a talent perspective, Dever-Boaz wanted a team that had speed and power. The team played in multiple, five-game series throughout the season, so pitching was also a top priority.

“The team we created was so well-balanced,” Dever-Boaz said. “We were looking for that speed and power, and we had that. We had a lot of home-run hitters. We were just a well-balanced team.”

Players from as far as California made the trip to Northern Virginia two weeks before the season began. But in a short amount of time, the team clicked and built a strong chemistry.

That was helped by the fact that the players did almost everything together. They visited local restaurants after every home game. Most of the players couldn’t permanently move to the area because of full-time jobs in other areas, so during the season they lived in dorms at GMU, paid for by the team.

“It was just like college,” Jackson said. “We created an environment where we could have fun off the field. It felt like we were invited into the family.”

So when the team started winning, it just made sense to the players.

“There was definitely a kind spiritual element, if you will, to the fan base and the team,” Fairchild said. “It was as much a close-knit family atmosphere as you were going to get.”

No stands, no money

But as the 2008 season began, the players had a problem: they weren’t getting paid.

Professional softball players generally do not receive much compensation. At the time, each team had a $100,000 salary cap. The Glory’s pitching staff made the most money, but the majority of players earned between $2,500 and $5,000 for a three-month season.

Now, that small but important amount of money was not coming in anymore.

“Some of those girls were playing six weeks without being paid,” Dever-Boaz said.

While Wilson did not recall checks getting paid that late, he admitted that checks came late on two occasions. Plans for a bridge loan did not go as planned, and the team was “tapped out at that point,” Wilson said.

In one instance that Wilson vividly remembers, the former owner drove to Philadelphia where the team was playing and told them personally that their checks would be late.

He offered any player who wanted to quit the team the permission to do so. But the players decided to stay.

To make matters worse, the team could no longer play at George Mason. The public university school system had to help pay for the $48.2 million in bills that had accumulated because of the Virginia Tech massacre in 2007, meaning budgets at all state universities, including GMU, were affected.

So, the team had to play at Westfield Softball Complex, located at Westfield High School in Fairfax, Virginia, meaning the team could not stay in the dorms at GMU.

“We really became a close unit then,” Dever-Boaz said. “We had nothing else but each other to really rely on.”

The team’s living arrangements had to be moved to hotel suites where they had access to kitchens in their rooms. But finding money for basic needs was still an issue, according to team photographer Sol Tucker, because he often helped players pay for food.

“They could no longer afford to even live,” Tucker said. “And these are our personal friends, so we fed them and hooked them up. But I couldn’t believe that he (Wilson) would do that to them.”

But Wilson was also having his own personal issue to deal with as well. Wilson didn’t have a business partner, so he was paying for most of the expenses out of pocket. That money began to run low, too, meaning one of the last proverbial pillars that was stabilizing the franchise was gone.

Ultimately, Wilson said, he underestimated the costs of owning a professional team. He didn’t foresee the challenges that came with getting sponsorship revenue for advertising and television revenue. And there were other costs like putting up lights at GMU’s field that ended up being too expensive for the team to afford.

“The operating costs were about what expected,” Wilson said. “It was more about the ability to create the revenue around some of the sponsorship and advertising and trying to fill the stadium so quickly.”

Eventually, the team could not afford to pay its debts and Wilson said he filed for bankruptcy. But he lost more than just a franchise.

“We lost our house and cars after all that happened,” Wilson said. “It was a good learning experience. I wouldn’t say that I wish I hadn’t done it. It was a phenomenal experience. But it was tough for a couple of years after that.”

The team lost the stands shortly after the move from GMU because it couldn’t afford them, which was a blow to the fan base. The team’s following was not as strong as it was at GMU, and the loss of the stands affected it even more.

“It was a heartache at that point because we knew it was the end of the franchise,” Dever-Boaz said. “And it was really sad for us at that point because there was a core of us that had become exceedingly close.”

After it became clear the Glory could not be financed, the National Pro Fastpitch league took control of the team. Although there were some talks with a potential buyer to keep the team in the area, that effort was unsuccessful and the team collapsed.

National Pro Fastpitch Commissioner Cheri Kempf refused to comment on the team, other than to say the Glory became insolvent and became unable from a financial standpoint to continue operations.

Although the team was defunct, the players’ contracts were sold to the newly-organized USSSA Pride for the following season. Most didn’t stay with the team, though. Dever-Boaz had recently stepped down from her position to spend more time with her family, as she originally planned two years earlier.

Jackson left shortly after moving to the Pride to pursue a career in coaching. Fairchild had left the previous year and is now coaching Division I softball herself.

But the players and coach still remember the team fondly. They still have good memories of those two years, even after the team went from being an integral part of their lives to a small piece of their careers in a span of months.

“It was a wonderful dream to bring a team into the community like that,” Wilson said. “It wasn’t the right timing. And looking back…if some things had happened differently, we probably could have been able to stick around.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.